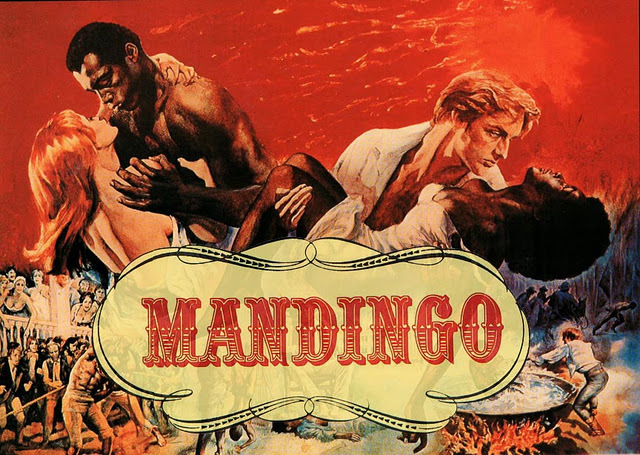

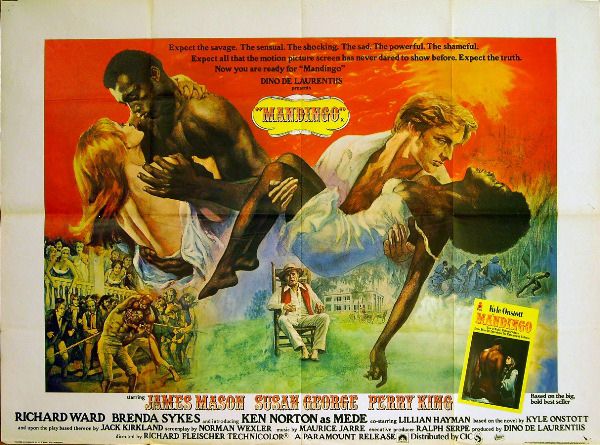

Mandingo (1975)

Dir: Richard Fleischer

"The greatest film about race ever made in Hollywood." - British film historian & critic Robin Wood

"This piece of manure...." - Roger Ebert

"One of the quintessential masterpieces of American filmmaking" - Timothy Sun

"This piece of manure...." - Roger Ebert

"One of the quintessential masterpieces of American filmmaking" - Timothy Sun

Mandingo - the controversy

The release in 2012 of Tarantino's Django Unchained, followed some months later by Steve McQueen's 12 Years a Slave, both of which focus on the subject of American slavery, and which share a Southern plantation setting, has revived interest in Mandingo, a 1975 movie whose subject is also slavery in the plantation South. Only Tarantino has openly acknowledged his movie's indebtedness to Fleischer's Mandingo and praised the film. McQueen's comments about his film incorrectly suggest that he rescued his source material (the memoir "12 Years a Slave") from oblivion and that his movie is almost unique in exposing the horrors of plantation slavery in the South.

Almost four decades before both Tarantino and McQueen revived the plantation slave movie, the veteran Hollywood director Richard Fleischer and the scriptwriter Norman Wexler made one of the 1970s most controversial and critically despised movies. Tarantino noted that it was one of mainstream Hollywood's first exploitation movies. For most critics it symbolised racist moviemaking at its worst. Variety decsribed it as "embarrassing and crude". For Roger Ebert, it was '"racist trash" and the New York Time's critic Vincent Canby called it "steamily melodramatic nonsense." Although the movie made money at the boxoffice, Mandingo quickly vanished from circulation. If it was ever shown at all it was at festivals of grindhouse movies or theaters to audiences of what Timothy Sun desribes as "porn-addled racists." [from Timothy Sun's fine article, ["Mandingo" http://notcoming.com/reviews/mandingo/]

Although some critics have described 12 Years a Slave as cinema's most horrific depiction of slavery - as a compliment, not a criticism -it hardly compares with the catalogue of vioelnce and atrocity offered by Mandingo. Apart from incessant racist remarks and incidents, there is incest, poisonings, murder by pitchfork, rape, a hanging, whippings, a cauldron of boiling water big enough to hold a man....

Director Richard Fleischer's justification for the movie's brutality was simple. " The whole slave story has been lied about, covered up and romanticised so much that I thoufght it really had to stop. The only way to stop it was to be as brutal as I could possibly be, to show how these people suffered. I'm not going to show you them suffering backstage - I want you to look at them." [Robert Keser, "The Eye We Cannot Shut - Richard Fleischer's Mandingo", The Film Journal] Timothy Sun [http://notcoming.com/reviews/mandingo/]

Almost four decades before both Tarantino and McQueen revived the plantation slave movie, the veteran Hollywood director Richard Fleischer and the scriptwriter Norman Wexler made one of the 1970s most controversial and critically despised movies. Tarantino noted that it was one of mainstream Hollywood's first exploitation movies. For most critics it symbolised racist moviemaking at its worst. Variety decsribed it as "embarrassing and crude". For Roger Ebert, it was '"racist trash" and the New York Time's critic Vincent Canby called it "steamily melodramatic nonsense." Although the movie made money at the boxoffice, Mandingo quickly vanished from circulation. If it was ever shown at all it was at festivals of grindhouse movies or theaters to audiences of what Timothy Sun desribes as "porn-addled racists." [from Timothy Sun's fine article, ["Mandingo" http://notcoming.com/reviews/mandingo/]

Although some critics have described 12 Years a Slave as cinema's most horrific depiction of slavery - as a compliment, not a criticism -it hardly compares with the catalogue of vioelnce and atrocity offered by Mandingo. Apart from incessant racist remarks and incidents, there is incest, poisonings, murder by pitchfork, rape, a hanging, whippings, a cauldron of boiling water big enough to hold a man....

Director Richard Fleischer's justification for the movie's brutality was simple. " The whole slave story has been lied about, covered up and romanticised so much that I thoufght it really had to stop. The only way to stop it was to be as brutal as I could possibly be, to show how these people suffered. I'm not going to show you them suffering backstage - I want you to look at them." [Robert Keser, "The Eye We Cannot Shut - Richard Fleischer's Mandingo", The Film Journal] Timothy Sun [http://notcoming.com/reviews/mandingo/]

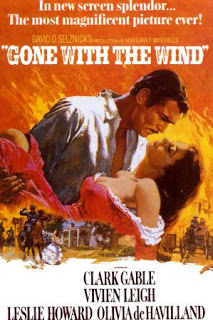

Mandingo: the anti-Gone With the Wind

Note how the Mandingo poster deftly appropriates one of the most iconic of all movie poster images: the Rhett/Scarlet embrace featured on most of Gone With the Wind''s posters. Mandingo' artwork appropriates the GWTW image and makes it bi-racial.

In one of the first signs that Mandingo was beginning to undergo a re-evaluation, in 2008 the New York Times (which 33 years earlier had vilified the movie, published an article by Dave Kehr which succinctly praised Fleischer's directorial talents especially in the genre of crime films. Kehr astutely classified Fleischer's 1975 slavery epic as the director's "last great crime film, in which the role of the faceless killer is played by an entire social system." He described it as

"an anti-Gone With the Wind that treats the pre-Civil War South as a swamp of degradation for white masters and slaves alike ....a thinly veiled Holocaust film that spares none of its protagonists."

One of the subtlest touches in this blunt and corrosive movie is its explicit contrasting of two southern plantations: the legendary Civil War era Tara of Gone With the Wind and Falconhurst, the 1840s slave-breeding Louisiana plantation home of the benighted Maxwell family.

In one of the first signs that Mandingo was beginning to undergo a re-evaluation, in 2008 the New York Times (which 33 years earlier had vilified the movie, published an article by Dave Kehr which succinctly praised Fleischer's directorial talents especially in the genre of crime films. Kehr astutely classified Fleischer's 1975 slavery epic as the director's "last great crime film, in which the role of the faceless killer is played by an entire social system." He described it as

"an anti-Gone With the Wind that treats the pre-Civil War South as a swamp of degradation for white masters and slaves alike ....a thinly veiled Holocaust film that spares none of its protagonists."

One of the subtlest touches in this blunt and corrosive movie is its explicit contrasting of two southern plantations: the legendary Civil War era Tara of Gone With the Wind and Falconhurst, the 1840s slave-breeding Louisiana plantation home of the benighted Maxwell family.

Mandingo's Falconhurst mansion is run-down, dingy and decaying, an apt architectural metaphor for the family and the society in which it is located. By contrast, Gone With the Wind's Tara has a beauty and grandeur (which admittedly will soon be destroyed in the war). The interiors of both mansions also provide revealings contrasts. Falconhurst is all enclosed sombre gloom and shadows, its frequently empty rooms and hallways conveying a mood of menace. The main focal points are, appropriately enough given the movie's sexual activities, dark bedrooms. But Tara is brightly lit, crowded and bustling, its various rooms large and full of social interaction. Significantly, Madingo shows slave huts (a feature copied in Django Unchained). Gone With the Wind's bucolic idealisation of plantation life has no time for such doses of realism .

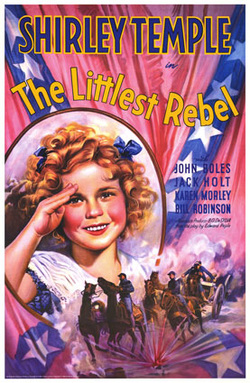

Gone With the Winds's images of cheerful. bustling and compliant slaves, devoted to their white masters and mistresses, loyal and a bit stupid set the template for Hollywood's portrayal of plantation slaves. Absent are scenes of sexual abuse, long hours of back-breaking work, vicious or degrading punishments. It's hard to imagine Tara's slaves for what they were - mere chattels, the property of their white owners. An even more saccharine and inaccurate picture of slave life is provided by another tremendously popular movie of the 1930s: the Shirley Temple musical-drama-comedy The Littlest Rebel. Here the cheerful slaves belonging to the child character's plantation-owning, Confederate officer father burst into cheerful song and dance, idolise the white folks, and seem to be part of one big happy plantation family. Such misleading images were replaced in Mandingo by scenes of squalor, degradation, depravity and abuse. Mandingo also went to considerable lengths to show how the pernicious values inherent in slavery harmed not only the slaves, but, more subtly, their owners and the whole fabric of southern life.

The Littlest Rebel is everything Mandingo is not: sentimental, charming in a saccharine way, and determined to present slavery and the white southern plantation way of life in the most favorable possible light. The slaves are shown as contented, cheerful members of a close-knit extended plantation community, reading to burst into song-and-dance at a moment's notice. They're honest,diligent toilers, contented with their lot, on great terms with their kind, thoughtful master , and fiecely protective of his little daughter when he is captrured by the Yankees during the Civil War. This benign and false image of the institution and the plantation South itself was the target of Mandingo's venom.

From vilification to admiration: why the shift in opinion about Mandingo ?

1. In recent years director Richard Fleischer's movie-making reputation has been favorably reassessed. For years Fleischer was regarded as just another Hollywood director, , capable and energetic admittedly, but whose prolific output (dozens of movies) and willingness to work in a variety of genres for big studios, plus the fact that some of his movies were very profitable, meant that for a long time his films were regarded as unworthy of serious discussion. But revisionist interpretations have created a new interest in many of the director's movies, including Mandingo. Thus Dave Kehr's 2008 article "In a Corrupt World, the Violent Bear It Away" describes Fleischer's best work as "meticulous", especially praising the director's pioneering film about serial killers (e.g. Compulsion, The Boston Strangler, 10 Rillington Place). Kehr follows the French critic Jacques Lourcelles in noting that a crucial motif in Fleischer's movie concerns "society slipping into decadence". Fleischer's most profound expression of this theme is to be found in Mandingo, Kehr believes. He writes

The treatment of humans as so musch chattel, to be bought, sold and cruelly abused ...makes "Mandingo" a thinly veiled Holocaust film that spares none of its antagonists. More than a portrait of social decadence, "Mandingo" is Fleischer's last great crime film, in which the role of the faceless killer is played by an entire social system."

[Kehr, New York Times, 17 February, 2008]

Robert Keser maintains that Mandingo is arguably Fleischer's best film, which "unflinchingly confronts all three hot wires of American history - race,class and gender - to dramatize a squalid chapter of capitalism without restraints." For Keser, Mandingo employs melodrama to show how slavery distorts all the human relationships, black and white, owners and human chattels alike, that it involves. [Robert Keser, "The Eye We Cannot Shut - Richard Fleischer's Mandingo", The Film Journal] Timothy Sun [http://notcoming.com/reviews/mandingo/] not only rescues Mandingo from the category of "trash cinema" - he hails it as "subversively exploitative", defends it from charges of racism and praises it as a "howl of outrage at a society that allows slavery to exist."

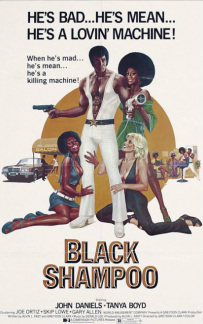

2. During the past decade or so, film critics and enthusiast have looked much more kindly at the so-called "exploitation" movie genre, priasing them for their subversive, non-traditional approach to controversial topics such as race, gender roles and violence. Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez, for example, have used the in-your-face techniques, styles and themes of exploitation movies. Tarantino's success and popularity as a director depends in large measure upon his constant ironic referencing of music, dialogue, actors and scenes from these movies. He has openly acknowledged Mandingo as a source for Django Unchained, and that film's slave fighting sequence is openly referred to as "Mandingo" fighting." But Tarantino's technique relies on distancing irony; Mandingo, however, does not soften its approach in this way.

The treatment of humans as so musch chattel, to be bought, sold and cruelly abused ...makes "Mandingo" a thinly veiled Holocaust film that spares none of its antagonists. More than a portrait of social decadence, "Mandingo" is Fleischer's last great crime film, in which the role of the faceless killer is played by an entire social system."

[Kehr, New York Times, 17 February, 2008]

Robert Keser maintains that Mandingo is arguably Fleischer's best film, which "unflinchingly confronts all three hot wires of American history - race,class and gender - to dramatize a squalid chapter of capitalism without restraints." For Keser, Mandingo employs melodrama to show how slavery distorts all the human relationships, black and white, owners and human chattels alike, that it involves. [Robert Keser, "The Eye We Cannot Shut - Richard Fleischer's Mandingo", The Film Journal] Timothy Sun [http://notcoming.com/reviews/mandingo/] not only rescues Mandingo from the category of "trash cinema" - he hails it as "subversively exploitative", defends it from charges of racism and praises it as a "howl of outrage at a society that allows slavery to exist."

2. During the past decade or so, film critics and enthusiast have looked much more kindly at the so-called "exploitation" movie genre, priasing them for their subversive, non-traditional approach to controversial topics such as race, gender roles and violence. Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez, for example, have used the in-your-face techniques, styles and themes of exploitation movies. Tarantino's success and popularity as a director depends in large measure upon his constant ironic referencing of music, dialogue, actors and scenes from these movies. He has openly acknowledged Mandingo as a source for Django Unchained, and that film's slave fighting sequence is openly referred to as "Mandingo" fighting." But Tarantino's technique relies on distancing irony; Mandingo, however, does not soften its approach in this way.

Slave life as presented in three movies & a featurette

(warning: Mandingo clip may offend)

|

|

|

|

|

|

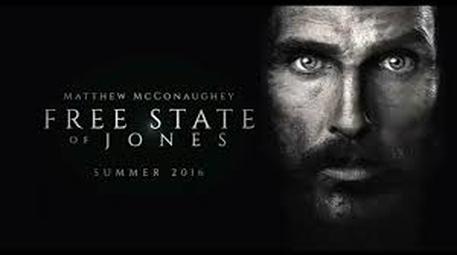

A new movie about race relations in the civil war South: Free State of Jones

Director Gary Ross's 2016 civil war era movie Free State of Jones takes a new perspective on race relations in the civil war era. It is based on an actual event: a revolt against Confederate rule in Jones County, Mississippi, 1862-1865. Non-slave-owning yeomen farmers in that area, led by Newton Knight, tried to break away from the Confederacy and set up their own independent state. The band of rebels within a wider secession were joined by local slaves and freedmen. Knight formed a relationship with one of them, and they had several children.