Was Martha Gellhorn really so significant as a woman war / foreign correspondent? Was she really a pioneering female journalist?

During the 1930s, World War II and post-1945 conflicts, Gellhorn was only one of several talented female war / foreign correspondents. Her more widespread public fame rested on her relationship with Hemingway and her skill in gaining publicity for herself and her work.

Three American Trailblazing Women Foreign / War Correspondents

|

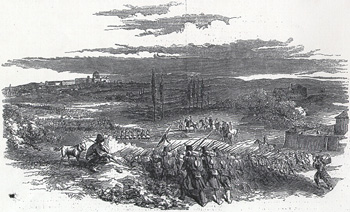

Margaret Fuller

Ninety years before Martha Gellhorn wrote about the effects of war on civilians, Margaret Fuller was graphically describing the consequences of the French army's siege of the short-lived Roman republic in 1849. Her gift for detailed observation anticipated and surpassed Gellhorn: "A pair of skeleton legs protruded from a bank of one barricade; lower, a dog had scratched away its light covering of earth from the body of a man, and discovered it lying face upward all dressed; the dog stood gazing on it with an air of stupid amazement." Margaret Fuller was in Rome during 1848-9 reporting for the New York Tribune on the Roman Republic that had been established by Guiseppi Mazzini, Guesippi Garibaldi and other Italian nationalists. Within months it was crushed by the French army. Fuller was working as the world's first accredited woman foreign / war correspondent. She also cared for the wounded in hospitals -and had a child by one of the wounded revolutionaries. Born in 1810, she was exceptionally intelligent, and proud of it. She became an early and important feminist, and was one of New England's leading intellectuals along with Emerson and Hawthorne. She drowned along with her partner and child in 1850 in a shipwreck off Fire Island, New York.was a radical feminist, author of the groundbreaking study Woman in the Nineteenth Century. Click for more about her life and work. |

Cora Stewart Taylor (Cora Crane)In 1897 another New York newspaper, the New York Journal declared that it had appointed Cora Stewart Taylor as what it called "the world's first woman war correspondent". Her mission was to cover a now almost forgotten conflict - the thirty-day war between Greece and Turkey over Crete. She was accompnaied by her partner, author Stephen Crane, of Red Badge of Courage fame. Writing as 'Imogen Carter', Taylor sent reports from the battlefield. Decades before Gellhorn her reportage focused on what was headlined as "War Seen Through a Woman's Eyes".

Taylor's life is fascinating, and provides enough scandal and adventure for several movies. She was born into a life of genteel Boston comfort in 1865 and for a time lived the life of a socialite while developing a skill as a short story writer. Then she moved to New York. She helped her first husband run a gambling house. She moved to England after divorcing him. Her second husband, Donald Stewart had aristocratic connections and spent much of his time abroad as a colonial administrator. Cora, now Lady Stewart, spent her time with London high society, and created a scandal with her affair with the heir to a banking fortune. She then took another lover, but quarreled with him on his private yacht , jumped overboard off the Florid coast and surfaced in Jacksonville. Here she called herself Cora Taylor, bought a hotel and rermodelled it as the Hotel de Dream - a nightclub/bordello. In 1896 she met the author Stephen Crane, famous for his Red Badge of Courage, who had been reporting on the Spanish-American war in Cuba. The pair became lovers until Crane's death in 1900. After jointly covering the Greco-Turkish war the couple moved to England, lived beyond their means and were lionized by the literary elite. After Stephen Crane's death (TB) at age 28, Cora returned to Jacksonville in 1901. Here she established an elaborate 14-bedroom two-storey "resort" i.e. brothel. Business was so profitable that she soon bought interests in other "resorts". In 1905 she married one of her bar managers, a 25 year-old scion of southern society. The marriage ended in divorce after her husband killed one of Cora's lovers ( as it was a crime of passion he escaped punishment). Cora, now writing as Cora Crane, then returned to journalism, writing for several leading American publications , including Harpers. She died in 1910, aged 45. |

Nellie BlyNellie Bly , the pseudonym for Elizabeth Cochrane (1864 - 1922) was probably the world's first female investigative and undercover journalist. She also served as a war / foreign correspondent in Mexico and during the first world war. Bly's main interest lay in exposing political and social injustices, such as treatment of the insane and working conditions for female factory workers, and the effects of the Diaz dictatorship in Mexico.

Cochrane was the daughter of a factory worker who eventually became a property magnate. She bceamne a journalist as a teenager by writing an indignant complaint to the Pittsburgh Dispatch about its misogynistic reporting. The editor was so impressed by the style and its argument that papers should write more about ordinary people, including women, that he eventually hired her. Writing as Nellie Bly, Cochrane quickly made a reputation both in America and abroad as both a foreigh correspondent and crusading journalist. Aged 21 she spent several months in Mexico, sending dispatches about poverty and hunger and exposing the violence and corruption of the Diaz dictatorship there. Years later in her fifties she covered the eastern front in World War I, writing as "Nellie Bly in the Front Line'. She also went undercover to investigate such issues as child labour and working conditions in factories, housing conditions and most famously, the treatment of the insane. In this case she faked insanity to gain admittance to a New York asylum for insane women. Her 10-day stay there eneabled her to reveal appalling treatment of inmates, gross incompetence, cruelty and neglicence by staff, as well as the horrifying fact that such hospitals were used by unscrupulous relatives to dump sane people in order to gain access to their financial and property resources. |

Martha Gellhorn's contemporaries: other women foreign / war correspondents

The 2012 HBO movie Hemingway & Gellhorn gives the impression that Martha Gellhorn was the only female war / foreign correspondent in the 1930s and 1940s, a pioneering figure in reporting. In fact, she was only one of several remarkable woman correspondents who covered war and conflicts from the 1930s to the 1960s. At least three of them outrated Gellhorn in the range and significance of their work. And her reporting of the Spanish Civil War with its focus on civilians and the Republicans was blatantly derived from the superb photo-journalism of Gerda Taro. But these women hadn't been married to one of twentieth century literature's seminal figures. Women like Clare Hollingsworth, Virginia Cowles and Marguerite Higgins faced the same prejudices and difficulties as Gellhorn, shared the same interest in reporting on the 'human face' of war, and were exposed to the same dangers. They also displayed a better awareness of the strategic -political significance of the conflct they were covering. One of them, the remarkable Gerda Taro, became the first woman war correspondent to report from the midst of front-line war and the first to be killed on the battlefield.

Gerda Taro (1910 - 1937)

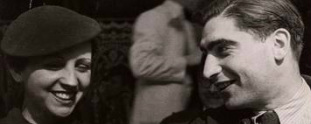

Until Gerda Taro's death, and the onset of the Hemingway-Gellhorn legend pushed them from the public gaze, she and her lover, Roberty Capo, were the 'glamour couple' associated with reporting on the Spanish Civil War. The pair were supporters of the anti-fascist republicans before that stance became fashionable amongst American and British literary elites. They arrived in Spain before Hemingway and Gellhorn, spent more time on the front lines than the two Americans, constantly exposed themselves to battlefield dangers (which eventually ended in Taro's death) and provide more extensively documented coverage of the war in words and photos than any other journalists. Capa since became legendary for his photo-journalism yet Gerda Taro is now an obscure figure. Yet her written and photographic accounts of the conflict, especially her moving portrayals of the innocent and suffering civilian victins of war, provided a model which Gellman copied in her journalistic contributions.

Gerda Pohorylle was born in 1910 into a Polish-Jewish family in Germany. When her family later moved to Leipzig she became involved in left-wing politics and shortly after the Nazis came to power to power in 1933 was arrested for participating in an anti-Nazi protest. After that she left for Paris and met a Hungarian photographer Andre Friedmann. The pair became lovers. Gerda developed her own photographic skills and helped organise Friedmann's business.They then reinvented themselves, constructing for Andre the fictional identity of 'Robert Capa' and for her 'Gerda Taro', names mimicking the Hollywood director Robert Capra and the star Greta Garbo.

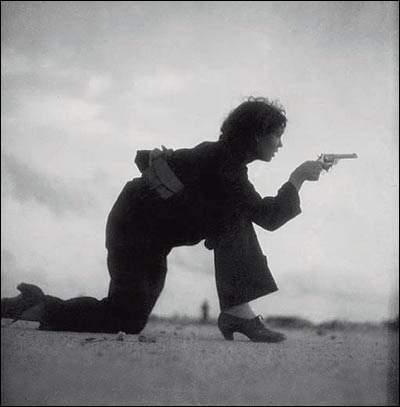

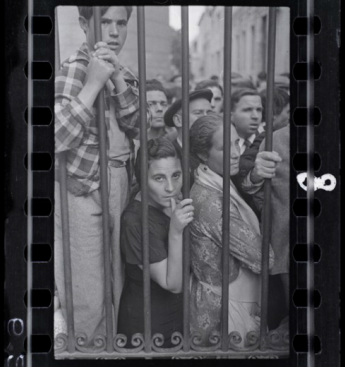

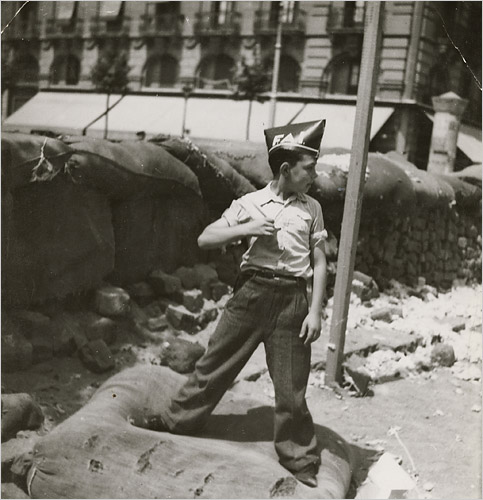

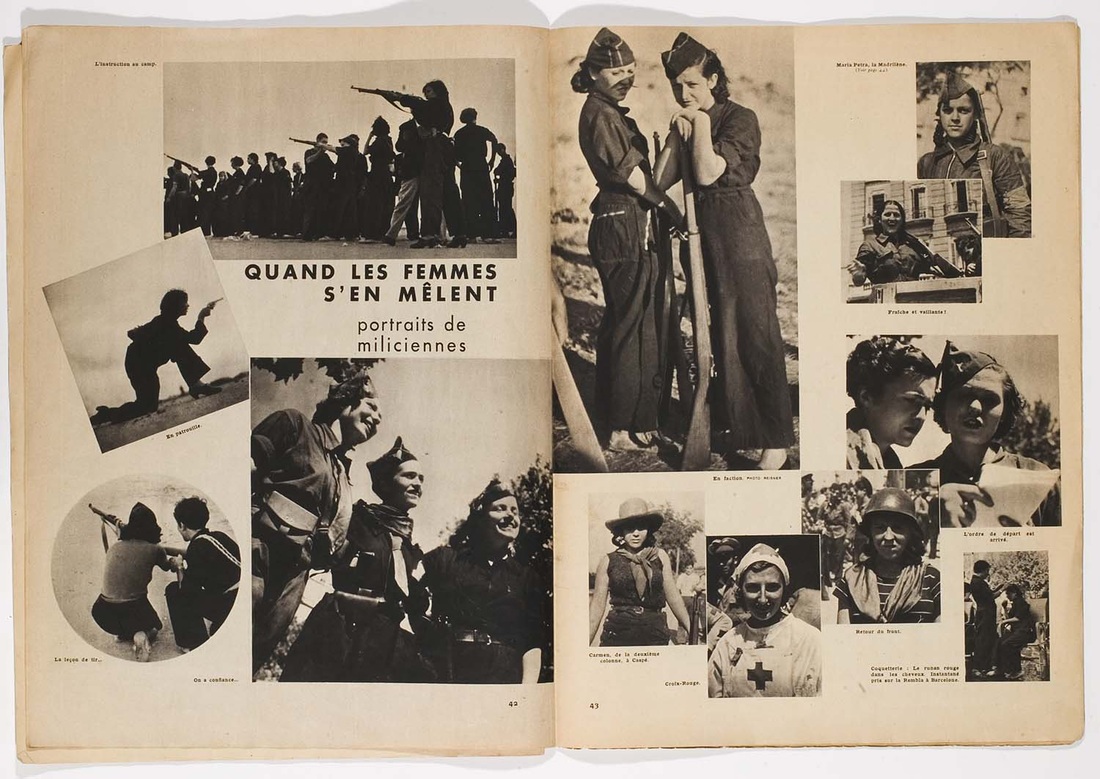

The pair left immediately for Spain when civil war broke out there in July, 1936. Both wanted to document the conflict and support the republican cause. They arrived weeks before the influx of foreign correspondents such as Hemingway and Gellhorn. They went to the front lines and besieged cities, accompanying the Republican forces and reporting, sometimes together, sometimes separately, sending in their photographic and written despatches.Their written and photographic work became increasingly sought after and the couple became for a time the heroic and glamorous face of reporting on the conflict. Gerda was an increasingly skilled photographer. In crucial ways she was a template for Gellhorn. She made full use of her good looks -Gerda was nicknamed La Pequena Rubia, "the little blonde"- and wore fashionable shoes and clothing to the frontlines. She and Capa were both well aware of the publicity and commercial value of a two lovers working together in war zones. She visited scenes of intense fighting, disregarded journalistic objectivity with her fervent support for the anti-fascist forces, and concentrated on documenting the war's impact on the most vulnerable. All these features were quickly taken up by Gellhorn when she arrived. Interestingly, while Tara's reporting made much of the role of Spanish women as republican militia, Gellhorn had little to say about this feminist aspect of the conflict.

In July, 1937 Taro went to Brunete, near Madrid, to report on the bitter fighting there. She was accompanied by her new lover, a Canadian journalist, Ted Allen. On 25 July the pair joined troops retreating from an air raid by jumping on the running board of a car. An out of control Republican tank hit the car, flinging Taro and Allen to the ground. She died the next day. Taro received a spectacular funeral in Paris, attended by thousands and where she was proclaimed an "anti-Fascist martyr".

Gerda Pohorylle was born in 1910 into a Polish-Jewish family in Germany. When her family later moved to Leipzig she became involved in left-wing politics and shortly after the Nazis came to power to power in 1933 was arrested for participating in an anti-Nazi protest. After that she left for Paris and met a Hungarian photographer Andre Friedmann. The pair became lovers. Gerda developed her own photographic skills and helped organise Friedmann's business.They then reinvented themselves, constructing for Andre the fictional identity of 'Robert Capa' and for her 'Gerda Taro', names mimicking the Hollywood director Robert Capra and the star Greta Garbo.

The pair left immediately for Spain when civil war broke out there in July, 1936. Both wanted to document the conflict and support the republican cause. They arrived weeks before the influx of foreign correspondents such as Hemingway and Gellhorn. They went to the front lines and besieged cities, accompanying the Republican forces and reporting, sometimes together, sometimes separately, sending in their photographic and written despatches.Their written and photographic work became increasingly sought after and the couple became for a time the heroic and glamorous face of reporting on the conflict. Gerda was an increasingly skilled photographer. In crucial ways she was a template for Gellhorn. She made full use of her good looks -Gerda was nicknamed La Pequena Rubia, "the little blonde"- and wore fashionable shoes and clothing to the frontlines. She and Capa were both well aware of the publicity and commercial value of a two lovers working together in war zones. She visited scenes of intense fighting, disregarded journalistic objectivity with her fervent support for the anti-fascist forces, and concentrated on documenting the war's impact on the most vulnerable. All these features were quickly taken up by Gellhorn when she arrived. Interestingly, while Tara's reporting made much of the role of Spanish women as republican militia, Gellhorn had little to say about this feminist aspect of the conflict.

In July, 1937 Taro went to Brunete, near Madrid, to report on the bitter fighting there. She was accompanied by her new lover, a Canadian journalist, Ted Allen. On 25 July the pair joined troops retreating from an air raid by jumping on the running board of a car. An out of control Republican tank hit the car, flinging Taro and Allen to the ground. She died the next day. Taro received a spectacular funeral in Paris, attended by thousands and where she was proclaimed an "anti-Fascist martyr".

Examples of Taro's photojournalism. Note her emphasis on women as combatants & civilians as casualties of war.

|

|

|

Virgina Cowles

|

The journalsit and author Geoffrey Moorehead described Virginia Cowles (1910 - 1983) as "bold, tenacious and tireless". Another author, John Julius Norwich described her as "one of the most attractive women I had ever met - and certainly one of the bravest." She relished the advantages that her good looks and femininity gave her in pursuing a story. "What a fine thing it was to be a female of the species" she wrote. Cowles also had an invaluable ability to make important contacts and shamelessly use them to obtain a story.

Her journalistic career had certain parallels with that of Martha Gellhorn, and the two were good friends. Cowles lacked the stylistic flair of Gellhorn, but had a better eye for the telling detail and was rather more succinct and measured than her friend. Cowles was the more reliable reporter: her approach was objective. For example, she reported on both sides of the Spanish conflict. However, she unashamedly advocated American entry into World War II. She also was much more assured than Gellhorn in placing her articles within a military of political context. And the grit and spectacle of war fascinated her -her journalism conveys a sense of personal enthusiasm and curiosity. Like Gellhorn, Cowles had little practical experience as a war correspondent before arriving in Spain. Aged 27, a correspondent for Hearst newspapers, (originally covering fashion) she arrived in Madrid in 1937 and became friendly with Hemingway, Gellhorn and other correspondents lodged at the Florida Hotel. She quickly became famous for investigating war damage in high heels and perfect make-up, but her stories were succinct, stylish and above all, balanced. She had the ability to go to exactly the right place at the right time. Cowles arrived in Berlin in time to hear Hitler declare war on Poland; she rushed to Paris in 1940 and drove a car to observe the approaching German army. After the war Cowles became roving correspondent for the Sunday Times. Cowles wrote a successful West End play about women war correspondents with Gellhorn. She then married, had three children and wrote several histroical biographies. She died in a car crash in 1983. |

Martha Gellhorn's and Virgina Cowles: literary collaborators

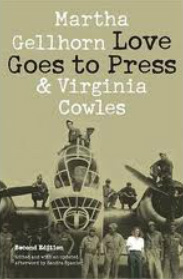

After the war ended Gellhorn and Cowles wrote a play about two women war correspondents. Gellhorn admitted that neither knew anything about playwriting and that their intention was to sell it to the movies to make money for them. A romantic farce set in a press camp in the Italian countryside during 1944, Love Goes to Press depicts two main female characters (Annabelle Jones = Gellhorn and Jane Mason = Cowles) who are beautiful, witty, talented and better at their job than their male counterparts. Each is ambitious and driven; each is lonely. Both characters have to deal with the problem of which side of her life should prevail: the personal / romantic or the professional / journalistic. The play's chief male role Joe Rogers, the ex-husband of Anabelle/Martha, a man whose personality resembles that of Ernest Hemingway and whom she had divorced because he has plagiarised her work, but for whom she still has some affection.

Love Goes to Press had a good run in London iduring 1946-7, gaining good notices. However it flopped badly when transferred to the New York stage. The play was revived in 2012 off-Broadway.

Love Goes to Press had a good run in London iduring 1946-7, gaining good notices. However it flopped badly when transferred to the New York stage. The play was revived in 2012 off-Broadway.

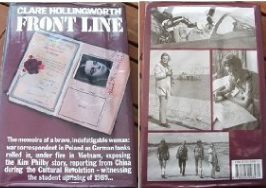

Clare Hollingworth

Asa war correspondent, Clare Hollingworth was undoubtedly a pioneer in one crucial aspect of that profession. She was the first woman correspondent top be recognised by her male peers as an expert commentator on the strategic and political background of the various conflicts that she covered. She was the first woman ever accredited as a newspaper's defence correspondent (for the then prestigious Guardian) She excelled, not in the human interest aspect of war journalism, but in the previously male-dominated field of on-the-spot analysis firmly anchored within the shifting contexts of local politics and history, and international strategy. Unlike Gelhorn and Taro, she remained unobtrusive: a half-century of her reporting on conflicts and wars provides remarkably few photos of her in the various locations locations she visited. Her perspective was slanted towards the left, but unlike Taro and Gellhorn,Hollingworth's coverage and commentary was much more objective. Neither provided the same massive scoops that Hollingworth regularly provided her editors.

Hollingworth was born in 1911 and celebrated her centenary surrounded by admiring journalists at the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club. From an early age she shared her father's interest in battlefields, and the events that led to conflict. Later in life her reporting always reflected his dictum that war and conflict were continuations of politics and must always be considered in a wider geo-political context. After leaving school she worked for the League of Nations Union [LNU] and studied Slavonic Studies at Lndon University and then Crotian at Zagreb University. A shared interest in central European politics led to her marriage in 1936 to an English LNU organiser. But she soon returned to Europe alone, to help distribute aid to the Jewish and left-wing refugees fleeing the Sudetenland ahead of the Nazi takeover.

By August 1939 Hollingworth had been a journalist for the Daily Telegraph for a few days, appointed by the editor on the basis of her knowledge of central European politics, especially Poland. At the end of the month she was returning by road to Poland from Germany when, near the border, part of a long line of tarpaulins flapped open, revealing German tanks, troop and artillery lined up. Hollingworth had gained an enormous scoop: the imminent German invasion of Poland. On 1 September she called the British embassy in Warsaw to inform them that the Germans had just invaded, holding her telephone out out the window to carry the sounds of invasion.

From now on Hollingworth followed the crisis-points of the war: Poland, Greece, Egypt. Here Montgomery ordered her out of the battlefield so she switched to following the Americans. Based on Cairo she covered the Middle East, learnt fly and to parachute-jump. She gained a reputation for courage, tenacity and energy. She disliked other women war correspondents and preferred the company of their male counterparts, although her lifestyle was otherwise ascetic.

After the war Hollingworth covered the Middle East, especially Palestine, with the journalist Geoffrey Hoare, whom she married in 1952. By this time the pair were wqorking in Paris. She covered the brutal Algerian war for independence in the 1950s and 1960s. She then went to Vietnam to cover that conflict. In 1973, aged 61 she became the Telegraph's first resident correspondent in Beijing. She retured froim the paper in 1981, but continued reporting from Hong Kong for another decade.

By August 1939 Hollingworth had been a journalist for the Daily Telegraph for a few days, appointed by the editor on the basis of her knowledge of central European politics, especially Poland. At the end of the month she was returning by road to Poland from Germany when, near the border, part of a long line of tarpaulins flapped open, revealing German tanks, troop and artillery lined up. Hollingworth had gained an enormous scoop: the imminent German invasion of Poland. On 1 September she called the British embassy in Warsaw to inform them that the Germans had just invaded, holding her telephone out out the window to carry the sounds of invasion.

From now on Hollingworth followed the crisis-points of the war: Poland, Greece, Egypt. Here Montgomery ordered her out of the battlefield so she switched to following the Americans. Based on Cairo she covered the Middle East, learnt fly and to parachute-jump. She gained a reputation for courage, tenacity and energy. She disliked other women war correspondents and preferred the company of their male counterparts, although her lifestyle was otherwise ascetic.

After the war Hollingworth covered the Middle East, especially Palestine, with the journalist Geoffrey Hoare, whom she married in 1952. By this time the pair were wqorking in Paris. She covered the brutal Algerian war for independence in the 1950s and 1960s. She then went to Vietnam to cover that conflict. In 1973, aged 61 she became the Telegraph's first resident correspondent in Beijing. She retured froim the paper in 1981, but continued reporting from Hong Kong for another decade.