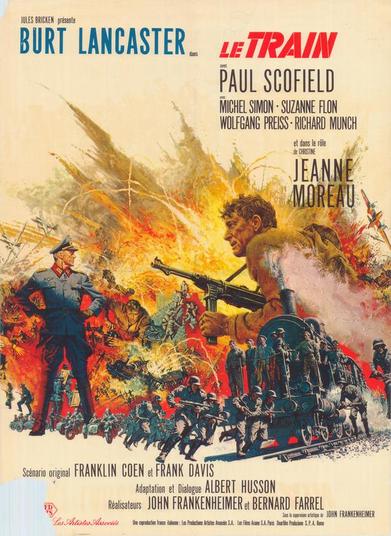

The Train (Dir: John Frankenheimer) 1964

An exciting, tense war film about the French resistance's attempts to stop a train carrying great art works stole by Germans from a French museum during the war. Not only has the movie invigorating and beautifully photographed and coordinated scenes of action, it also has important points to make about war's brutalizing effects, the French resistance movement and whether the preservation of culture (in the form of great museum art) overrides the sanctity of human life.

The making of The Train

This 1964 movie, now regarded as both a classic war film and one of the very best movies about the French Resistance, was briefly in the directorial hands of Irving Penn. But the film's star and driving force Burt Lancaster was unhappy with Penn's rather cerebral apporach, and he called in John Frankenheimer, with whom he had recently made the critically acclaimed political thriller Seven Days in May and also Birdman of Alcatraz. Another recent Frankenheimer success had been The Manchurian Candidate, one of the greatest political film noirs.The movie which Frankenheimer took over was loosely based on a book, Le Front de l'art, by a quiet, unassuming, former member of the Resistance, Rose Valland, which describes how she and others thwarted a German plan to rob France of its finest art collections. The German occupiers were stripping the contents of various key French galleries and museums, storing them at Paris' Jeu de Paume museum (where Vallard worked) and 'transfer' them by rail to Germany.

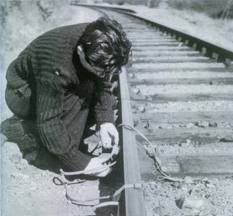

The movie's plot, set in late 1944, follows the efforts of a German Colonel Von Waldheim to organise a train to transport the valuable art works to Germany. The French resistance sets out to prevent this. Waldheim gives Labiche, the Paris railway superintendent (and member of the Resistance), the job of ensuring the train transfer of the art goes smoothly. Labiche, however, is also instructed by his Resistance superiors to prevent the train leaving France with its cultural cargo. He and his resistance workers devise a plan that is ingenious (and very cinematic). One of the pleasures of seeing this film several times is to appreciate the ways in which the movie exploits compressed time sequences and the mechanisms of running a railway system to ratchet up the tension, and also reveal character.

The movie's plot, set in late 1944, follows the efforts of a German Colonel Von Waldheim to organise a train to transport the valuable art works to Germany. The French resistance sets out to prevent this. Waldheim gives Labiche, the Paris railway superintendent (and member of the Resistance), the job of ensuring the train transfer of the art goes smoothly. Labiche, however, is also instructed by his Resistance superiors to prevent the train leaving France with its cultural cargo. He and his resistance workers devise a plan that is ingenious (and very cinematic). One of the pleasures of seeing this film several times is to appreciate the ways in which the movie exploits compressed time sequences and the mechanisms of running a railway system to ratchet up the tension, and also reveal character.

The history behind The Train

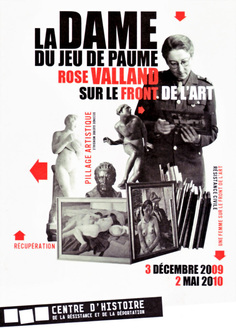

The Train is loosely based on Rose Valland's efforts to foil the German Occupying forces attempts to steal French art from French museums and art galleries, and private -especially Jewish - collections, and ship them off to Germany where they would be 'appropriated' as spoils of war by various high-ranking Nazis, officials and military. Her character appears in the movie, and there is an effective scene between 'Vallon" and von Waldheim, as the curator tries to find more about the Germans' intentions without revealing the extent of her own knowledge as to what they are up to.

Rose Valland (1898-1980), had several degrees in art history and fine arts by the start of the war. Unassuming, self-effacing, and rather plain and dour in appearance, she was working as a curator in Paris' Jeu de Paume gallery in the Tuileries Gardens when the Nazi Occupying forces took it over and used it as a depot to store artworks stolen from private French collections, mainly Jewish. The quiet, eficient Valland, who concealed her German-speaking ability in order to eavesdrop, oversaw the steady accumulation of looted artworks. Her knowledge of shorthand helped her to carefully record what art was being stored and transferred, and its destination. She passed this information, which included details of which trains were carrying the plundered art to Germany, on to her contacts in the Resistance. Her main contact was Jacues Jaujard, Director of National Museums, who had established links with the Resistance. Valland even copied negatives of the photos the Germans made of each item stored in the gallery. A typical message to Jaujard (3 January, 1943) told him that "75 bottles of champagne, 21 bottles of cognac, 16 Flemish and Dutch paintings left the Jeu de Palme at the request of M. Goring to celebrate his birthday." But all she could do after witnessing the burning, in the garden of the Jeu de Palme, of several hundred "degenerate" paintings by Picasso,Miro and others, was inform Jaujard "Impossible to save anything." [Alan Riding, And the Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris (London, 2011), p.166 ]

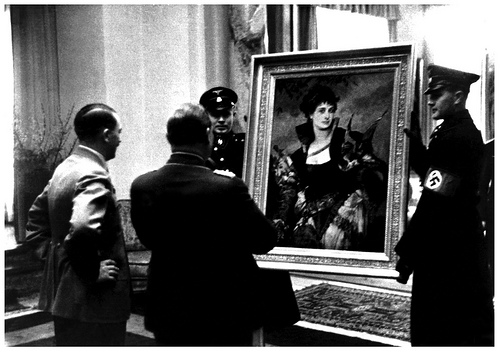

Her surreptitious role became even more important when under Hitler's orders, the Jeu de Paume became headquarters for the Special Staff for Pictorial Art, a section of the ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg), itself a unit of the Foreign Affairs Division of the Reich. Alan Riding, whose book on cultural life in Paris under the Occupation is essential reading for anyone interested in the period of Occupation and the Resistance, describes how when Goring first visited the Jeu de Paume in November, 1940

" he was stunned by what he saw, and what, in effect, he was being offered.

For Goring's inspection, the Jeu de Paume had been arranged like a nineteenth

century museum, with hundreds of paintings covering the walls of two floors,

plus a good masny more displayed on the racks. "

Riding, And the Show Went On , p.162.

By late 1944 the Germans planned to get rid of their looted art and send it by train to Germany. Riding describes how Valland

" learned on August 1. 1944, that five cars of train No.40,044 were being

loaded with 148 cases of art ...tipped off the Resistance, which kept the train

from leaving Alnay, on the outskirts of Paris." Riding, p.167

Thereafter, the Resistance used a combination of bureaucratic paper-shuffling, altering railway routes, rescheduling and sabotage to ensure that the train with its cargo of cultural riches never left Paris. Not as exciting as the events of The Train, but still effective. The movie, however, was accurate in its insistence on the detailed knowledge of exactly what art works the Germans possessed, the importance of inside information about German plans to move the stolen art to Germany, and the Resistance's use of the railway system to thwart the German plans. A recent book on the topic of Nazi art theft , The Monuments Men: Allied heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History by Robert Edsel examines the role of the U.S. government in recruiting a team of art experts in tracing stolen art. George Clooney is currently making a movie out of it. It is too be hoped that Vallon's vital role is recognised.

Rose Valland (1898-1980), had several degrees in art history and fine arts by the start of the war. Unassuming, self-effacing, and rather plain and dour in appearance, she was working as a curator in Paris' Jeu de Paume gallery in the Tuileries Gardens when the Nazi Occupying forces took it over and used it as a depot to store artworks stolen from private French collections, mainly Jewish. The quiet, eficient Valland, who concealed her German-speaking ability in order to eavesdrop, oversaw the steady accumulation of looted artworks. Her knowledge of shorthand helped her to carefully record what art was being stored and transferred, and its destination. She passed this information, which included details of which trains were carrying the plundered art to Germany, on to her contacts in the Resistance. Her main contact was Jacues Jaujard, Director of National Museums, who had established links with the Resistance. Valland even copied negatives of the photos the Germans made of each item stored in the gallery. A typical message to Jaujard (3 January, 1943) told him that "75 bottles of champagne, 21 bottles of cognac, 16 Flemish and Dutch paintings left the Jeu de Palme at the request of M. Goring to celebrate his birthday." But all she could do after witnessing the burning, in the garden of the Jeu de Palme, of several hundred "degenerate" paintings by Picasso,Miro and others, was inform Jaujard "Impossible to save anything." [Alan Riding, And the Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris (London, 2011), p.166 ]

Her surreptitious role became even more important when under Hitler's orders, the Jeu de Paume became headquarters for the Special Staff for Pictorial Art, a section of the ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg), itself a unit of the Foreign Affairs Division of the Reich. Alan Riding, whose book on cultural life in Paris under the Occupation is essential reading for anyone interested in the period of Occupation and the Resistance, describes how when Goring first visited the Jeu de Paume in November, 1940

" he was stunned by what he saw, and what, in effect, he was being offered.

For Goring's inspection, the Jeu de Paume had been arranged like a nineteenth

century museum, with hundreds of paintings covering the walls of two floors,

plus a good masny more displayed on the racks. "

Riding, And the Show Went On , p.162.

By late 1944 the Germans planned to get rid of their looted art and send it by train to Germany. Riding describes how Valland

" learned on August 1. 1944, that five cars of train No.40,044 were being

loaded with 148 cases of art ...tipped off the Resistance, which kept the train

from leaving Alnay, on the outskirts of Paris." Riding, p.167

Thereafter, the Resistance used a combination of bureaucratic paper-shuffling, altering railway routes, rescheduling and sabotage to ensure that the train with its cargo of cultural riches never left Paris. Not as exciting as the events of The Train, but still effective. The movie, however, was accurate in its insistence on the detailed knowledge of exactly what art works the Germans possessed, the importance of inside information about German plans to move the stolen art to Germany, and the Resistance's use of the railway system to thwart the German plans. A recent book on the topic of Nazi art theft , The Monuments Men: Allied heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History by Robert Edsel examines the role of the U.S. government in recruiting a team of art experts in tracing stolen art. George Clooney is currently making a movie out of it. It is too be hoped that Vallon's vital role is recognised.

One aspect that the movie emphasises is the question of the relative value of great art versus human lives. In The Train the German von Waldheim seizes hostages to ensure that the shipment of art reaches its destination; he is quite prepoared to execute civilians in order to ensure the 'preservation' of what he regards as cultural treasures. But for the Resistance's Labiche, the value of the art is ephemeral compared with the lives of the hostages. In a scene with Vallon (played by Suzanne Flon), Labiche suggests blowing up the train and its cargo of art; no work of art is worth a single human life..This moral-philosophical conflict becomes the effective climax of the movie. Interestingly, it's also a theme hinted at in one of the very first and best French movies about the nature of the Resistance and the individual's complicity in evil - J.P. Melville's Silence of the Sea.

A movie about the French Resistance that raises moral and cultural issues within the context of a tense thriller

Burt Lancaster's shrewd eye for movies that combined action / tension with comment on contemporary political issues and/or investigation of moral and cultural problems along with his entrepreneurship and knowledge of movie production values made him the ideal foil for John Frankenheimer. The director shared the star's interest in setting action with a social-cultural context, and had a superb ability to create fast-moving scenes of tension and violence, employing a semi-documentary style that also utilised high overhead shots, sustained panning and travelling shots and extreme close-ups, often filemd in noirish and lustrous black- and-white. But Frankenheimer also had a tendency to unsubtly impose his ideas on the film, occasionally overwhelming the plot and characters with profound moral or political statements. Fortunately, Lancaster's production prowess and authority held this aspect of Frankenheimer in check, notably in The Train. Here Frankenheimer's admiration of Italian neo-realisim cinema become clear: the documentary aspect, the emphasis on day to day working lives, minimal use of background music, a disdain for sentimentality. And some of the set-pieces are remarkable, especially the bombing raid on a Paris rail way depot which remains a masterpiece of visceral visual and aural technique. The Train is one of those rare films that stand up to repeated viewings, in which the cleverness of the real-time sequences, the cunning and intricate ways in which the Germans are deceived and the convincing acting and terse, jolting scenes of conflict and action become even more convincing.

|

|

|

Sequence showing Spitfire mistakenly attacking Resistance train Documentary on making of movie (in French)