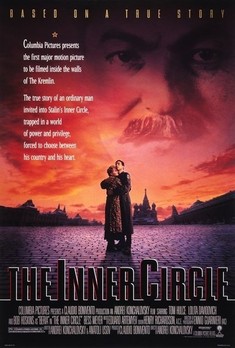

The Inner Circle (1991)

A controversial look at Russian dictator Stalin through the eyes of his projectionist

|

|

What's it all about?

Above: Hulce, with secret police chief Beria on right (Bob Hoskins) and Stalin (Alexandr Zbruyev). The Inner Circle, Russian director Andrei Konchalovsky's fact-based 1991 movie, looks at the difficult and contentious topic of Stalin's and his autocracy through a unique perspective -that of a very ordinary Russian who was the dictator's projectionist for two decades. The movie's central character, called Ivan Sanshin, (Tom Hulce), is a fictionalisation of Aleksandr Ganshin, the actual projectionist who really did show Stalin and his sycophantic favourites films for almost two decades. Ganshin, (who had worked in the NKVD club in the Kremlin as a projectionist and then in the Film Ministry) had been summoned to the job at about 2 a.m. early one August 1935 morning. by the feared three rings on his doorbell. He was taken away by men from the NKVD [secret police]. Expecting to be arrested, Ganshin was told that Stalin needed a new projectionist to show the various movies that the dictator loved to see late at night, Stalin was a genuine movie buff, especially fond of Hollywood musicals, westerns and the Marx Brothers. He also considered himself an expert on Soviet cinema, offering "advice" on scripts, music, subject-matter and ideological content. Ganshin even served as adviser on the film. He remained an admirer of Stalin and resented the tentative recent steps made in the late 1980s to make Russia a more open and democratic society. Hulce, who met Ganshin, noted that "When he speaks of his former employer a light shines in his eyes--he still loves Stalin deeply, as do many people in Russia. It's truly a cult. I remember Ganshin saying to me, 'All I need is a bed to sleep in and food to eat. Freedom? Who needs it!' " The movie refuses to demonise Stalin; it cleverly gets us to laugh at some of his antics and jokes, while showing him to be resourceful, articulate, witty and coolly manipulative. As portrayed by Alexandr Zbruev (whose father was one of the many executed on Stalin's orders) comes across as a benign, avuncular figure, even rather charming - unless his ministers and cronies. Konchalovsky claimed "I made Stalin charismatic because I wanted him to be seen as he was through the eys of his admirers, and because I believe that ultimate evil often dresses in the most attractive dress." However, the director also shows this apparently sympathetic persona is cleverly contradicted by Stalin's contemptuous treatment of his inner sycophantic circle, his tolerance of their acts of evil and by their obvious fear of their leader as they spend night after night wining and dining and watching movies with Stalin, all the while terrified by the knowledge that he may have already marked them for death. For Konchalovsky, the figure of Sanshin / Ganshin became what he described as "the drop of water through which one can see the entire ocean." In a move that probably doomed the film's American box-office prospects, Konchalovsky subverts the Hollywood cliche of the ordinary man gaining heroic stature by standing up to evil. Instead, projectionist Sanshin - like Stalin's inner circle - chooses to ignore the openly-displayed evidence of evil that he witnesses in his job and his daily life, succumbing to the privileged lifestyle provided by his job and Stalin's favor. In one scene, when asked by his wife Anastasia whom he loves more, her or Stalin, he replies "Stalin" as if that is the only possible answer. Sanshin, like his counterpart in real life, worships Stalin. Eventually he even refuses to take action when his fictional) wife Anastasia, movingly portrayed by Lolita Davidovitch, eventually becomes another sexual victim of Stalin's secret police chief, Laventri Beria. The real moral center of the movie is not the projectionist - it is his wife. Anastasia, who eventually rejects her husband's hero-worship of Stalin and acknowledges that he is a tyrant under responsible for a reign of terror and vice ends up suffering for her small but brave acts of resistance and humanity. The contrasting attitudes of husband and wife epitomise Konchalovsky's theme: that the rule of Stalin was made possible by most Russians' supine acceptance of a vicious regime and by their blind adulation of a leadership that they secretly know is monstrous. "No questions!" is Sanshin's (and their) motto. Konchalovsky's entirely pessimistic message (another resaon for his movie's box office failure)) is that at heart most Russians are only too willing to accept a tyrant. Stalin's rule rested on the approval of a people who chose authoritarianism over democracy. Konchalovsky's assertion that "Stalin wouldn't have been possible without people like Ivan because it was millions of Ivans who deified him," seems even more prescient with the rise of Putin and his consolidation of untrammelled power. Konchalovsky and Alexander Lipkov's book The Inner Circle: an Inside View of Soviet Life Under Stalin (New York,1991) edited by Jamey Gambrell is a fascinating source of information, including archival photos. |

|

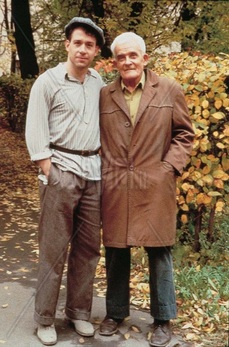

The Inner Circle's Director:

The inspiration for The Inner Circle's director, Andrei Konchalovsky came some twenty years before he made the film. One of his films was about to be screened for censorship and he promised the projectionist a bottle of brandy in return for feedback on its reception. The projectionist turned out to be Ganshin, who cheerfully told the director about his days showing films to Stalin and his cronies in the Kremlin and at Stalin's sprawling, luxurious dacha (semi-rural residence). Konchalovsky's film career is interesting. Born in 1937, initially keen on music, he went to the State film school -a fellow student was the seminal Russian director Tarkovsky with wheom he later collaborated on two of the latter's movies. Konchalovsky's second film ran into Soviet censorship problems but he gradually made his name as an accomplished director, with a disparate range of subjects: life in post-revolutionary Russia, a saga about Russian gentry in the 19th century, an adaptation of Checkhov's Uncle Vanya. He moved to the West in 1979 and now moves between Russia and western Europes. He then made some movies and TV series in Hollywood [e.g. Runaway Train] and directed plays and operas in Paris and other European cities. |

|

Is the movie accurate in its depiction of secret police chief Beria?

In the movie the figure of secret police chief Laventri Beria (Bob Hoskins) serves as the embodiment of Stalin's tyrannical rule. Hoskins' portrayal of Beria as a devious, opportunistic, bullying politician and a vicious sexual predator (and a contrast to the movie's apparently warmer, subtler Stalin) has been supported in recent years by the release of previously concealed documentary evidence. Beria (as Stalin and his ministers knew) was a truly monstrous figure - a serial rapist, torturer and murderer, who had his victims' bodies buried in the cellars of his Moscow house. Parts of their skeletons and grisly evidence of their deaths have been found. The Inner Circle was accurate in suggesting that Beria was a crucial figure in Stalin's government. "Our Himmler" Stalin described him to President Roosevelt at Yalta in 1945. LIke Stalin, Beria was born in Georgia and took part in Georgian revolutionary activities,although apparently he and Stalin did not meet until 1932. Stalin enjoyed talking to him in the distinctive Georgian language. He became head of CHEKA (the Bolshevik secret police) and by the mid-1930s had ruthlessly made his way up the ranks of the Cheka's successors, ending up in 1939 as head of the NKVD. Beria was a brilliantly efficient administrator of the terror and espionage network. He supervised Stalin's late 1930s purge of the armed forces [at least 30 000 Red Army officers killed], the NKVD itself and the establishment of the slave labor camps [the Gulag] in which millions of Russians were sent. "The Gulags existed before Beria," according to Anton Anton-Ovseyenko, a Russian historian, "but he was the one who built them on a mass scale. he indistriualised the gulag system."He also supervised Russia's atomic bomb project. After Stalin's death in 1953 Beria was an incredibly powerful figure: deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Internal Affairs i.e. in charge of both the secret police and regular police. But in July, 1953, some of his colleagues, realising he intended to grab absolute power, had him arrested, stripped of his posts and charged with high treason (spying for Britain). He was executed, possibly that month or in December. He was cremated and his ashes scattered by a huge fan. [See 'Stalin's Depraved Executioner' article] |

|

Posters glorifying Stalin (clockwise, from top right): Stalin as the great helmsman; Stalin as staunch defender of the Motherland; as leader of the masses of the world's masses; early 21st century admirer with poster of Stalin in religious icon pose; and Stalin as strategic genius.