Christopher Nolan's Epic War Movie

Director Christopher Nolan's powerful and fast-moving film about the Dunkirk evacuation has caused comment and controversy about several aspects of the events highlighted in the movie/

SOME TALKING POINTS ABOUT ASPECTS OF NOLAN'S VERSION OF THE EVENTS AT DUNKIRK

1. THE CRUCIAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE EAST MOLE

Nolan's Dunkirk movie restores a little-known aspect of the evacuation - the crucial significance of the nondescript East Mole in Dunkirk harbour.. It has been taken for granted that the evacuation of Allied troops was largely achieved by their being taken directly off the Dunkirk beaches, either directly by the famous civilian fleet of small vessels, or conveyed to waiting naval and other larger ships. In fact, about 70% of the troops were evacuated by way of what the French called the Jetee de l'est, or what the British came to call the East Mole. This was an unglamorous 1280 metre long breakwater, extending from old shore fortifications to the harbour mouth. Its base was tumbled stone (perhaps concrete in places) on top of which were embedded tall wooden pilings, which were in turn covered with a flimsy wooden walkway about two metres wide. In effect it became a pier along which rescue ships could precariously berth to embark troops.

For the curious, the strange word "mole" comes from a 16th Century Middle French word meaning "breakwater", in turn taken from Latin "moles" = barrier, large structure.

1. THE CRUCIAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE EAST MOLE

Nolan's Dunkirk movie restores a little-known aspect of the evacuation - the crucial significance of the nondescript East Mole in Dunkirk harbour.. It has been taken for granted that the evacuation of Allied troops was largely achieved by their being taken directly off the Dunkirk beaches, either directly by the famous civilian fleet of small vessels, or conveyed to waiting naval and other larger ships. In fact, about 70% of the troops were evacuated by way of what the French called the Jetee de l'est, or what the British came to call the East Mole. This was an unglamorous 1280 metre long breakwater, extending from old shore fortifications to the harbour mouth. Its base was tumbled stone (perhaps concrete in places) on top of which were embedded tall wooden pilings, which were in turn covered with a flimsy wooden walkway about two metres wide. In effect it became a pier along which rescue ships could precariously berth to embark troops.

For the curious, the strange word "mole" comes from a 16th Century Middle French word meaning "breakwater", in turn taken from Latin "moles" = barrier, large structure.

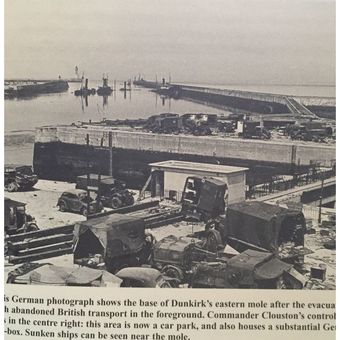

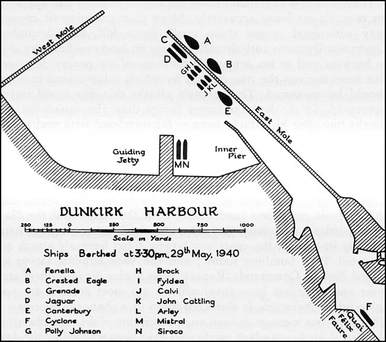

Top two images clearly show the structure of the East Mole and how ships moored alongside to embark soldiers.

Bottom right image shows how vessels berthed alongside the pier. Bottom left is a clipping showing aftermath of evacuation. It clearlyshows the considerable length of the East Mole as well as the amount of equipment the Allied forces had to abandon.

THE PIERMASTER AT DUNKIRK; WHO WAS HE?

In Nolan's movie, the Piermaster - naval officer in charge of embarkation is a fictional figure - named Commander Bolton) - and is portrayed by Kenneth Branagh in a manner familiar to older viewers who watched Kenneth More portray dozens of stoic British pilots, soldiers and naval officers in war movies of the 1950s and 1960s. The actual Piermaster was W.G.Tennant, who had been sent to Dunkirk as Senior Naval Officer by Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay, along with a staff 0f 12 officers and 150 seamen. Tennant and his team managed to impose order and a systematic approach onto a chaotic scene on the beach. Tennant later explained to his superiors:

As regards the bearing and behaviour of the troops, British and French, prior to and during the embarkation, it must be recorded that the earlier parties were embarked off the beaches in a condition of complete disorganisation. There appeared to be no military officers in charge of the troops …. it was soon realised that it was vitally necessary to dispatch naval officers in their unmistakable uniform with armed naval beach parties to take charge of the soldiers on shore immediately prior to embarkation. Great credit is due the naval officers and naval ratings for the restoration of some semblance of order. Later on, when troops of fighting formations reached the beaches, these difficulties disappeared.

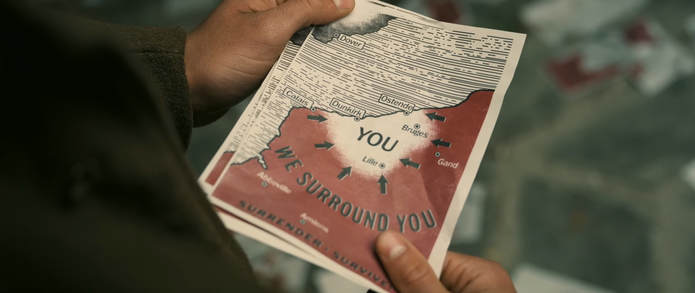

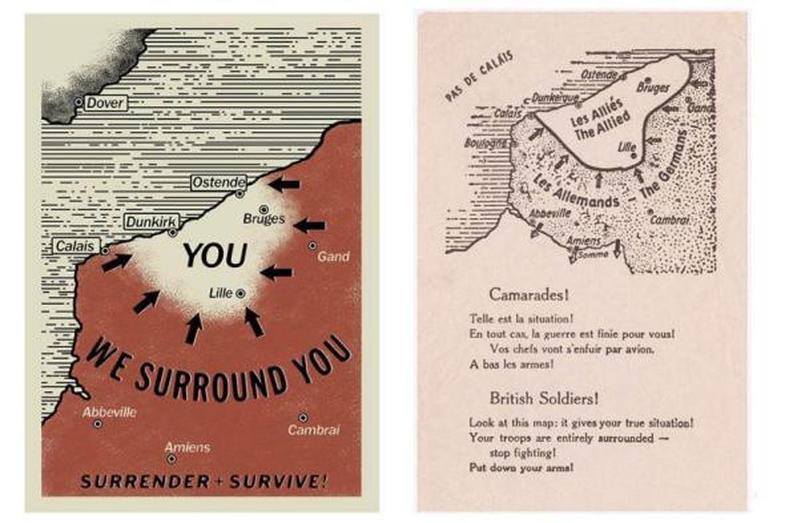

2. Did the Germans really drop leaflets urging Allied troops to surrender at Dunkirk?

They certainly did, and the movie's closeup shot below of a leaflet is a perfect copy of one of the actual leaflets shown below . Note that one of the leaflets is in French as well as English.

p.387 =To this day the raiment legend of Dunkirk centres on the “little ships” and the beach, but [Tennant wrote “The deserters put up by far the finest show of any of the forces concerned with the evacuation. After them I would put the personnel ships [passenger streamers], closely followed by some of the officers and men of the beach parties, who worked waist deep in water getting men away until they practicecally dropped in their tracks.

302 15 May only 5 days after German attack on France & low countries, announcement in Times user headline ‘Motor-bOat Census’ “The Admiralty HAS MADE AN ORDER REqUIRING ALL OWNERS OR OCCUPIERS OF SELF-PROPELLED CRAFT (INCLUDING MOTOR BOATS) IN BRITAIN BETWEEN 30FT AND 100 FT IN LENGTH USE FOR THEIR OWN PLEASURE OR FOR FARE-PAYING PASSENGERS FOR PLEASURE .. TO SEND PARTICULArS To THE ADMIRLATY with 14 days of yesterday.’

According to Michael Korda's account, Ramsay was "the architect of the plan for saving ... [the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk]".

According to Michael Korda's account, Ramsay was "the architect of the plan for saving ... [the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk]".

ostensibly for minesweeping dutiesHowever, in the RAF's defence, some of their activity against German aircraft and ground forces necessarily occurred away from the immediate environs of the Dunkirk, unobserved by British troops on the ground. And the RAF action over Dunkirk had to be fought with seriously depleted numbers. Previous aerial combat over France meant the RAF had lost a staggering 386 Hurricanes alone and 60-odd light bombers, plus 74 pilots killed or captured. Thus the RAF had only about 200 planes to try to protect the troops on the beaches, and only 60 bombers to attack German troops and weapons. And the heavy losses meant that many of the pilots and crew were inexperienced in aerial combat and tactics. It was also necessary to ensure that the RAF had sufficient aircraft to ensure that they could form the nucleus of the forthcoming German aerial onslaught on the UK.

Douglas C. Dildy, Dunkirk 1940: Operation Dynamo (Oxford, 2013)