Hollywood versus Pinewood Pt.2: Two Rival Attitudes to American Movies

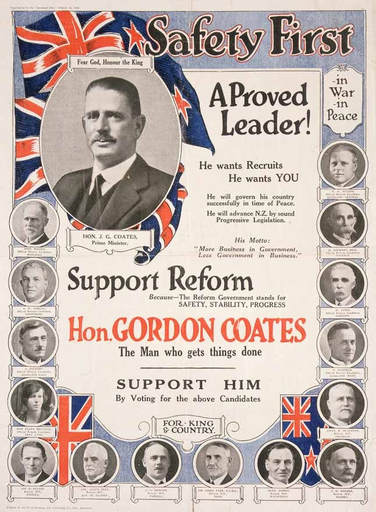

In 1925 J.G. (Gordon) Coates won the general election at the head of the reform Party and became one of New Zealand's youngest Prime Ministers (at age 37) .His victorious election campaign aimed to convey a sense of youth, dynamism and progress allied with stability and prudence. This election poster layout was modern for its time: nite the use of photos and several slogans. A woman even appears as a member of the Coates' team. Coates promised to modernise New Zealand, yet on cultural issues especially cultural links with Britain he was conservative. Note the use of union jacks on the poster to emphasise links with the U.K.

Throughout the 1920s at the same time as the New Zealand public flocked to see Hollywood movies, New Zealand's Anglophile cultural, social and political elites did their best to condemn, restrict and even ban them. But there was a fissure in this apparently impregnable wall of opposition to American movies. Interestingly, this was shown by a dispute over the issue between J.G. Coates and George Forbes, two of the leading politicians of the inter-war era. Surprisingly, Coates, who made much of his progressive attitudes , was very much old-school in his views on the then controversial issue of the influence of Hollywood movies and their alleged infiltration of 'traditional' New Zealand cultural cultural links with the UK..

These apprehensions about the cinematic infiltration of American mores into ‘British’ nations were addressed when Coates returned from the 1927 Imperial Conference in London. The impact of American movies had been discussed there, with the result that in 1928 the New Zealand parliament debated the 1928 Cinematograph Film bill.76 The key provisions of this legislation imposed a quota; by the end of 1929 five per cent of films must be of British origin, with the proportion rising to twenty per cent by 1939. In Coates’ words, this provision ‘cop[ied] almost exactly the legislation adopted in the Old Country’ the previous year, thereby enacting ‘the expressed wish’ of the Conference ‘that the Dominions should ... fall into line and assist the production of films within the British empire’. He was unequivocal about the legislation’s aim: its purpose is to give our people, particularly the younger ones, a clearer idea of British history, of British countries, and of British customs and ideals. I think we all recognize the great importance of bringing before our people the institutions and heroic events of our nation, and of imbuing them with a livelier sense of British ideals.... I feel it is of the greatest importance that our people should have a true perspective of events as seen through British eyes.78 Waitemata’s M.P. Alexander Harris supported Coates’ concerns over American films as a transmitter of American values. He claimed that ‘it is undesirable that our boys and girls who frequent picture-theatres should have nothing but the Stars and Stripes put in."

Condemnation of Hollywood movies was also common amongst New Zealand's inter-war intellectuals. For example, John Beaglehole who would eventually become a world-renowned authority on James Cook's explorations, wrote about seeing his first "talkie... an appalling thing called The Fox Movietime 1929 Follies; appalling both in construction, speech, song and everything else ....We couldn't stand it, & left half-way." Beaglehole noted disdainfully that "it was a Yank picture, & I hadn't seen a Yank picture for a long while. I didn't realise how shockingly bad they were beside these European ones I have been seeing lately."

In 1926 Coates told Parliament that ‘[t]he undesirability of presenting to the growing generation of New Zealanders’ ideals and viewpoints that are not British cannot be over- emphasized’. Similar sentiments were expressed by Wellington North’s M.P., Sir John Luke. He maintained that the proposed quota was necessary because [i]t is very evident that attending the picture-shows week after week, as most of the young people of this country do, and seeing nothing but American films ... is not at all helpful to them, and is not building up a national character along the lines we so much desire’. Another M.P. even objected to ‘the showing of films from any British-speaking country other than Great Britain and the dominions...."

It took the future Prime Minister George Forbes to inject some liberal arguments into the debate. He declared that he could not ‘see the necessity’ of inculcating British values in New Zealander movie audiences by insisting that they see a certain proportion of British films. Whereas some parliamentarians asserted that New Zealanders’ movie-watching preferences required paternalistic guidance and control in order to preserve their British identity, Forbes maintained that they were perfectly capable of making their own choices. A national identity, he argued, could not be imposed from above; it must grow from within. The public wish to see what they consider interesting or amusing. There is no use trying to force indifferent films, even of British origin, on the people of New Zealand.... the same kind of restriction could be placed upon the literature brought into this country. Forbes, unlike some of his contemporaries in the civic elites, had faith in the New Zealand public’s cultural judgement. He admitted that New Zealanders didn’t watch British films simply because they regarded that country’s cinema as inferior to its American counterpart. ‘[I]t is absolutely hopeless to attempt to foist on the people by compulsion something that has not merit.’ He denied that the ‘influence’ of American films was eroding ties with Britain. ‘British sentiment was never stronger in this country than it is at present, and I do not believe that the showing of British films or American films will affect it in the slightest degree.’ Forbes also rejected claims that New Zealanders’ national identities were bending in the direction of the United States as a result of the cultural buffeting inflicted by American culture. Our attachment to the Mother-country has not grown up like a hot-house plant, it has grown strongly without any artificial aid; and the suggestion that it is necessary to foster a proper British spirit by insisting in [sic] the showing of British films is unwarranted. New Zealanders are quite able to see films and read literature produced by other than Britishers without allowing themselves to be detached in their regard for the Empire.... Our affection for the Old Land has been, and is, based on ties of blood and common interests. I do not 79 NZPD Vol. 219 (1928), p. 332 80 NZPD Vol. 219 (1928), p. 341 81 NZPD Vol. 219 (1928), p. 347 204 think it is such a sickly plant that we need to exclude from this country the films of foreign lands.82 Forbes’s description of America as ‘foreign’ is revealing. It signifies an insistence – at least by New Zealand’s interwar political elite - that the U.S.A. was not considered an integral aspect of a wider Anglophone community, and that America remained for some a culture and society alien to New Zealand’s ostensibly British cultural heritage. The debate over film quotas was doubly significant. Not only did it reveal that concerns over the impact of American culture were now included alongside traditional issues such as trade and defence as providing parameters for defining New Zealand’s imperial relationship with Britain. It also enables us to view in a fresh perspective James Belich’s thesis that the interwar era was part of a decades-long process of ‘recolonisation’. The passage of the 1928 statute, with its use of British legislation as a template, and the insistence of some parliamentarians that quotas were necessary to maintain the nation’s British ‘tradition’, initially suggests that the dominion was indeed renewing its cultural and emotional links with the United Kingdom. Yet the very fact that it was found necessary to consider such legislation at all, and to voice concerns about the strength and efficacy of these ties, indicates that New Zealand’s relationship with the ‘mother country’ was evolving and expanding its parameters rather than relapsing into its former framework. Forbes’ attitude to the quotas shows an acceptance of this trend. He was not denying or rejecting the Dominion’s traditional associations with Britain. Instead he argued that New Zealand had now reached a more confident stage in its development, in which cultural identity could neither be imposed by legislation nor endangered by the impact of American media such as films.

1

1