New Zealanders' Love of Movies 1900s - 1956

"Our public is film-mad – Hollywood mad." -NZ Magazine, Vol 24 No.6, 1944

"We New Zealanders are a nation of film fans" - Gordon Mirams, Speaking Candidly, 1945

"We New Zealanders are a nation of film fans" - Gordon Mirams, Speaking Candidly, 1945

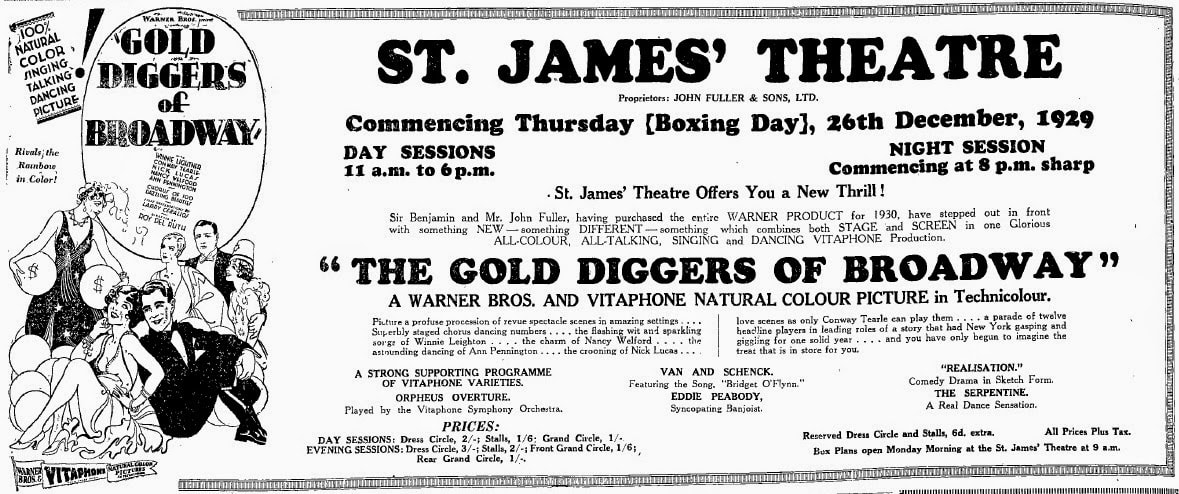

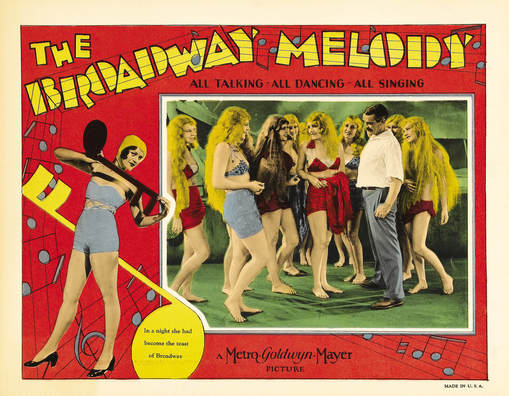

Popular Hollywood movies were shown in New Zealand just a few weeks after their overseas release. This 1929 ad shows that an Auckland cinema showing Hollywood's latest hit musical . Like its big-city American counterparts it also provided continuous sessions and live entertainment.

At the opening of Auckland’s huge Civic Theatre opened in December 1929 a crowd of thousands pushed inthe doors and staff were so busy that they threw handfuls of money into the box-office safe, unable to count it.

At the opening of Auckland’s huge Civic Theatre opened in December 1929 a crowd of thousands pushed inthe doors and staff were so busy that they threw handfuls of money into the box-office safe, unable to count it.

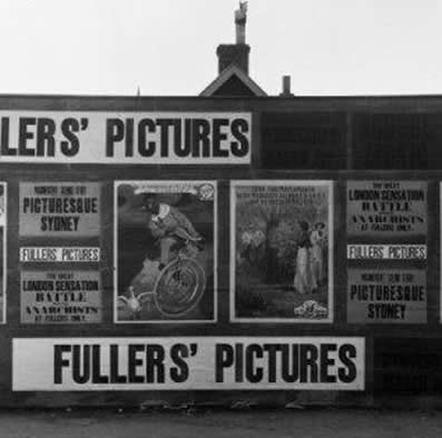

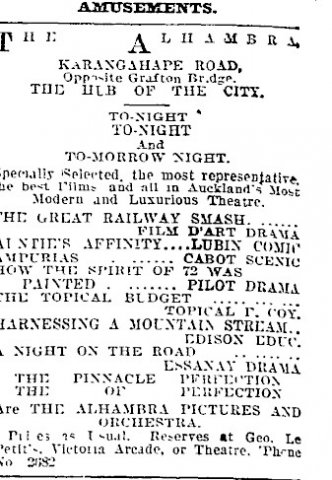

Films were a feature of New Zealand social and cultural life from the earliest days of commercial cinema. Only ten months after the world’s first public cinema screening in December 1895, a motion picture was shown in Auckland, using an Edison projector imported from the United States. A decade later Aucklanders could see, a few months after its American release, the first 10, 000 foot long movie - America at Work. The next year the Queens cinema in Auckland adopted the American city custom of having continuous screenings, from 11:00 a.m to 11 p.m. By the end of 1916 that city had thirteen inner-city picture theatres. By the end of the 1920s, one sixth of the population of Auckland went to the movies each Saturday night.

By the late 1930s New Zealand had one cinema seat for every six New Zealanders; the American ratio was one in twelve. In New Zealand there was one ‘picture theatre’ for every 3000 of the country’s population, while the United States had one for every 8700 people.19 By 1947 there were 33.6 cinemas for every 100 000 people, in contrast to 12.5 in the U.S.A., 11.3 in Britain and 20 in Australia. In 1943-4 each New Zealander on average attended the cinema on 23.4 occasions that year.20 A decade later that average was 18.1, which ranked New Zealand second only to the United Kingdom (25.0) on international attendance figures and ahead of the United States, which ranked fourth with a figure of 16.4.

189

The popularity of movies with New Zealanders was cemented in 1929, with the arrival of sound. When the De Luxe theatre in the small Horowhenua town of Levin installed ‘talkie’ equipment, bus services were re-organised in order to take residents from even small neighbouring towns such as Shannon into Levin for matinees and evening sessions. And when Whakatane’s Grand Theatre showed Broadway Melody, so many travelled over rough roads from isolated settlements such as Te Puke that a special 11:30 p.m. session had to be held.

By the 1920s foreign observers commented on New Zealanders' infatuation with the cinema -especially Hollywood movies. In 1929 the United States Commerce Department published a bulletin Motion Pictures in Australia and New Zealand. Its author, Eugene Way, noted that for New Zealanders – ‘well-educated, healthy, sports-loving’ – cinema-going was a popular activity. He observed that "90 per cent of the films shown in New Zealand were of American origin",noting that "programs are very similar to those seen in the United States. All the feature pictures are exhibited only a few weeks after their release on Broadway ... the picture fan frequently sees many American pictures before they have been made available to the smaller American communities....the average motion-picture house in New Zealand is a comfortable, luxurious building ... comparable with theaters in cities of similar sizes in the United States. Orchestral selections, organ solos and other features precede the showing of the film, and every care is taken to cater to the desire of the public." Way also claimed that New Zealander cinema audiences enjoyed the ‘adaptation of well-known novels, society drama and light comedies’, but disliked ‘morbid and melancholy tragedy films."

Eugene Way, Motion Pictures in Australia and New Zealand (Dept of Commerce Trade Information Bulletin No.608 1, U.S. Govt Printing Office, 1929), p.39; 41; 43-4

This movie-mania had a mixed reception. In 1944 the periodical NZ Magazine observed disapprovingly, ‘[o]ur public is film-mad – Hollywood mad. Our public is so hungry for celluloid tales well presented – and Hollywood has the technique – that they will roll up afternoon and evening and cheerfully swallow the fare provided, without being too fussy about the details’"

In 1945 the public intellectual, film reviewer and future film censor, Gordon Mirams, wrote anxiety, stylish and controversial book on New Zealand's film culture. It was the first time that cinema-going in New Zealand was treated as a serious subject providing insights into New Zealand's society and culture. Its key passage boldly asserted that

"We New Zealanders are a nation of film fans. Only tea drinking is a more popular diversion with us than picture-going. We adopted the motion picture earlier and more enthusiastically than most other countries, and today we spend as much time and money at the pictures, per head of population, as any other people in the world, except the Americans –and even they are not very far ahead of us. It follows that our picture-going habit exerts an enormous influence upon our manners, customs, and fashions, our speech, our standards of taste, and our attitudes of mind. If there is any such thing as a ‘New Zealand culture’, it is to a large extent the creation of Hollywood."

It is indicative of the cinema's popularity in New Zealand for at least five decades, and its role as a focus of New Zealand communal and recreational activity during this period, that both biographies and literature of several of the key post- World War2 poets, novelists and scholars fondly reference both the cinema, especially its Hollywood connotations. The poet and historian Keith Sinclair described how in the late 1920s "[o]n Saturday afternoons most of the kids used to go to matinees at the picture theatre, the Ambassador ....the children ...screamed with delight at the cartoons and western serials’.[Sinclair, Keith, Halfway Round the Harbour: an Autobiography (Auckland: Penguin, 1993), p.31.] The internationally renowned novelist Janet Frame’s account of her youthful enthusiasm for the cinema emphasises American filmstars:

"Now that we “went to the pictures” every week, a new selection of ambitions in a completely new world was offered to us. Myrtle, who did resemble Ginger Rogers with her golden hair, planned to be a dancer or a film star or both.... I had dreams of being a blind violinist, but, more practically, because I had curly hair and dimples, I also saw myself as perhaps another Shirley Temple." [ Janet Frame, To the Is-Land (New York: George Braziller, 1983), p.92 ]

When poet James K. Baxter wrote a lyrical account of his teaching life in the remote settlement of Akitio in the fifties, he depicted the local ‘cinema’ as the focus of the small community’s entertainment. Films were shown every second Saturday in the ‘landing shed’ ... a large barnlike structure near the beach on the property of a local farmer and used until the nineteen-forties for storing wool’.

Another of New Zealand's finest poets, Kendrick Smithyman, sometimes evoked his childhood experiences of movie-going in his poems. Outlooks. for example. portrays the New Zealand film-going experience as both a communal event and a social highlight in rural areas:

Years ago, on Saturday

Nights, farmers and villagers, Timbermen and gumdiggers,

My fable’s staunchest people

Not wholly predictable

Nor all to be believed

Having little they believed

In but their deluded strength

To endure, their common breath Not purposed for glory’s end, Would stay the work of the hand To get to the picture-show...

Yet, as we looked hard abroad

On the world which was displayed To us in our village Hall,

There was a question: Does all

Go shivering, screened by rain?

This primal sense of the audience participating in a communal experience can also be found in that most cinematic (and neglected) of New Zealand novelists, Ronald Hugh Morrieson. As Daniel Craig points out, Morrieson’s superb novel The Scarecrow utilises the serial conventions of 1950s Hollywood horror and noir films.26 It contains an affectionate description of the cinema of Klynham, the fictional stand-in for Hawera hometown of his childhood and adolescence in the interwar years.

"It was a big draughty barn of a place, but many happy hours we spent therein....I recall it fondly the way it was in the days when Les and I sat enthralled by a serial picture called ‘The King of Diamonds’, and the kids stamped on the floor and whistled at each certificate of approval, unless it was a travel film and then they hooted and groaned. There was always a chance of my bare arm brushing against the electrically charged flesh of Josephine McClinton again as we crowded down the stairs at interval, or even maybe, some day, fluking a seat alongside her. There were big pictures of Tom Mix and Robert Montgomery and June Withers on the walls of the stairway...."27

It is indicative of the cinema's popularity in New Zealand for at least five decades, and its role as a focus of New Zealand communal and recreational activity during this period, that both biographies and literature of several of the key post- World War2 poets, novelists and scholars fondly reference both the cinema, especially its Hollywood connotations. The poet and historian Keith Sinclair described how in the late 1920s "[o]n Saturday afternoons most of the kids used to go to matinees at the picture theatre, the Ambassador ....the children ...screamed with delight at the cartoons and western serials’.[Sinclair, Keith, Halfway Round the Harbour: an Autobiography (Auckland: Penguin, 1993), p.31.] The internationally renowned novelist Janet Frame’s account of her youthful enthusiasm for the cinema emphasises American filmstars:

"Now that we “went to the pictures” every week, a new selection of ambitions in a completely new world was offered to us. Myrtle, who did resemble Ginger Rogers with her golden hair, planned to be a dancer or a film star or both.... I had dreams of being a blind violinist, but, more practically, because I had curly hair and dimples, I also saw myself as perhaps another Shirley Temple." [ Janet Frame, To the Is-Land (New York: George Braziller, 1983), p.92 ]

When poet James K. Baxter wrote a lyrical account of his teaching life in the remote settlement of Akitio in the fifties, he depicted the local ‘cinema’ as the focus of the small community’s entertainment. Films were shown every second Saturday in the ‘landing shed’ ... a large barnlike structure near the beach on the property of a local farmer and used until the nineteen-forties for storing wool’.

Another of New Zealand's finest poets, Kendrick Smithyman, sometimes evoked his childhood experiences of movie-going in his poems. Outlooks. for example. portrays the New Zealand film-going experience as both a communal event and a social highlight in rural areas:

Years ago, on Saturday

Nights, farmers and villagers, Timbermen and gumdiggers,

My fable’s staunchest people

Not wholly predictable

Nor all to be believed

Having little they believed

In but their deluded strength

To endure, their common breath Not purposed for glory’s end, Would stay the work of the hand To get to the picture-show...

Yet, as we looked hard abroad

On the world which was displayed To us in our village Hall,

There was a question: Does all

Go shivering, screened by rain?

This primal sense of the audience participating in a communal experience can also be found in that most cinematic (and neglected) of New Zealand novelists, Ronald Hugh Morrieson. As Daniel Craig points out, Morrieson’s superb novel The Scarecrow utilises the serial conventions of 1950s Hollywood horror and noir films.26 It contains an affectionate description of the cinema of Klynham, the fictional stand-in for Hawera hometown of his childhood and adolescence in the interwar years.

"It was a big draughty barn of a place, but many happy hours we spent therein....I recall it fondly the way it was in the days when Les and I sat enthralled by a serial picture called ‘The King of Diamonds’, and the kids stamped on the floor and whistled at each certificate of approval, unless it was a travel film and then they hooted and groaned. There was always a chance of my bare arm brushing against the electrically charged flesh of Josephine McClinton again as we crowded down the stairs at interval, or even maybe, some day, fluking a seat alongside her. There were big pictures of Tom Mix and Robert Montgomery and June Withers on the walls of the stairway...."27

Why was cinema, which essentially meant American cinema, so popular and so emotionally and culturally resonant in New Zealand for over half a century?

Richard Waterhouse’s comprehensive explanation for the initial appeal of movies to Australians surely applied to New Zealanders: the combination of low prices, the medium’s technological novelties and its ‘adaptability to the rhythm of city life, providing a range of sessions to cater to a variety of recreational needs’. For Mirams, local enthusiasm for movies reflected New Zealand’s geographic isolation and the consequent expense and difficulty of importing other cultural forms: ‘... films can be packed in cans’.29 Bruce Babington suggests that until the late arrival of television in New Zealand, the nation had few highly developed non-sporting leisure activities to compete with movies. He also argued that in geographically isolated New Zealand, before the arrival of television and the internet, movies provided one of our ‘primary windows on the world – the large windows of a small room....

The poet and essayist Peter Wells adopts a similar view. He believes that films possessed a ‘peculiar power over New Zealanders, partly because every one of us, regardless of race, is unavoidably shaped by distance.... cinema became our form of foreign travel’. Wells maintains that cinema was popular here because it offered New Zealanders a means of vicarious escape.

'Why would we want to see our own country? Didn’t it wait to ambush us the moment the lights went up, and the doors burst open and we ran out like an exploding packet of hundreds-and-thousands. Wasn’t this precisely why we were all huddled in the dark, at our votive stations? To escape the endless nausea of living in a small and distant island? To escape the prairie of asphalt, the stern ancestral eyes of our telegraph poles? Of course we didn’t want to see our own country.'

Bruce Babington suggests that until the late arrival of television in New Zealand, the nation had few highly developed non-sporting leisure activities to compete with movies.30 He also argued that in geographically isolated New Zealand, before the arrival of television and the internet, movies provided one of our ‘primary windows on the world – the large windows of a small room....’

The poet and essayist Peter Wells adopts a similar view. He believes that films possessed a ‘peculiar power over New Zealanders, partly because every one of us, regardless of race, is unavoidably shaped by distance.... cinema became our form of foreign travel’. Wells maintains that cinema was popular here because it offered New Zealanders a means of vicarious escape:

Why would we want to see our own country? Didn’t it wait to ambush us the moment the lights went up, and the doors burst open and we ran out like an exploding packet of hundreds-and-thousands. Wasn’t this precisely why we were all huddled in the dark, at our votive stations? To escape the endless nausea of living in a small and distant island? To escape the prairie of asphalt, the stern ancestral eyes of our telegraph poles? Of course we didn’t want to see our own country.

Wells believes that for midcentury New Zealanders, to watch a film was ‘in essence, to browse, to mope joyously through an eternal and shuffling catalogue of things we didn’t have’: vehicles, cars, modes of socialising, dressing and living. ‘We learnt how to be citizens of the world – clumsily, it must be admitted – through the dumbshow of cinema.’ He also believed that New Zealanders were attracted by the very technology of cinema. ‘In a country dominated by old automobiles, where anything technical could be mended and massaged so it might last, films had about them the very scent of technical invention: magic made visual’.

Hollywood made the exotic and the wondrous available to Wellington and Whakatane alike, transported the sounds and images of overseas to rich and poor, all made equal in a darkness illuminated only by a translucent and flickering cone of light, providing a feast for the starved imagination.

There were other reasons reasons why New Zealanders flocked to see movies. An officer who questioned a discussion group of 2nd NZEF personnel in 1944 on their attitudes to the ‘pictures’ concluded that ‘Servicemen and women make no bones about the motives behind picture attendance. These are either escapism or habit: “Why do I go to the movies? Because my girl-friend (substitute ‘wife’ where applicable) likes to go out on a Saturday night..... Apart from the younger candid souls who go in pursuit of “a bob’s worth in the dark”, and that select minority who scan the advertisements to find a programme that appeals to them, the bulk of servicemen go from habit or for want of something better to do... A majority in these groups agreed that they went to see films for relaxation and amusement, though there were a few who said they went for educational reasons...."

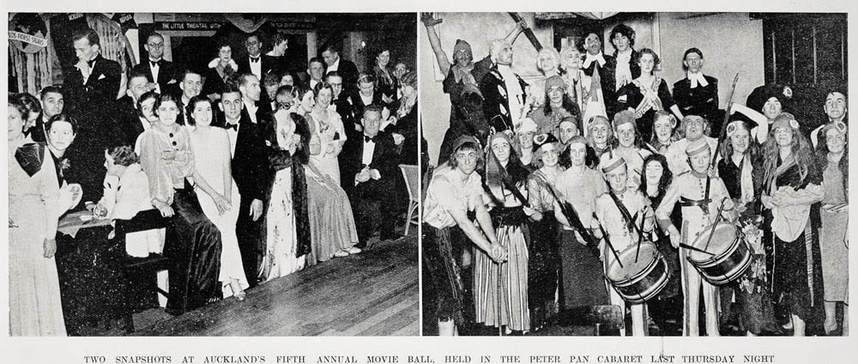

In pre-television New Zealand towns and cities, watching movies was a crucial part of the Saturday night social matrix. A visit to the ‘pictures’ was, for many, the first half of the evening’s double bill. Some small rural halls put away prjectors, screens and chairs to clear the wooden floor for dancing. Across the nation, after the movie, many singles and couples would often walk, bike, bus or drive to the nearest dance.One Greymouth youth, who met his future wife in this way, described how ‘buses were laid on from Greymouth and return. The buses left from the picture theatres at 10 p.m. after the movies had finished ... effectively dancing commenced around 10.30....'

Whether the moviegoer was a rowdy schoolboy rolling jaffas down the aisle during a Saturday afternoon Tim Holt western, a teenage couple on their first date, or grandparents having a night out, going to ‘the pictures’ was a staple of New Zealand communal life for decades.

Richard Waterhouse, Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: a History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788 (Sydney: Longman Australia, 1995), p. 181

Gordon Mirams, “The Cinema As a Social Influence”, Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society ofNew Zealand, Vol.77 (1948-9), p.343; Mirams, Speaking Candidly, pp.8-9]

Bruce Babington, A History of the New Zealand Fiction Feature Film (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), p.1;p.2

Peter Wells, On Going To the Movies (Wellington: Four Winds Press, 2005), p.8; 24; 16

Peter Wells, On Going To the Movies (Wellington: Four Winds Press, 2005), p.8; 24; 16;33;36

‘Movies For the Millions: Soldiers Are Keen Critics’, Korero, Vol. 2 No.10 (22 May, 1944) p.10;12

‘Movies For the Millions: Soldiers Are Keen Critics’, Korero, Vol. 2 No.10 (22 May, 1944) p.10;12

Reminiscences of Bernie Wood, in Georgina White, Light Fantastic: Dance Hall Courtship in New Zealand (Auckland: HarperCollins, 2007), p.149