The Imitation Game: Turing, Bletchley Park and the Soviet Spy

One of the most controversial features of the The Imitation Game involves the clumsy subplot featuring the espionage carried out at Bletchley Park by the Soviet spy, John Cairncross, one of the codebreakers there. The movie shows Cairncross as one of the key members of Turing's team - a gross inaccuracy, as Turing never worked with Cairncross and probably was unaware of his existence. As Turing's biographer Andrew Hodges points out, "their relationship was invented." Cairncross's excellent knowledge of German language and literature meant that he worked at Bletchley as a translator; he was never involved in the mathematical aspects of breaking the Enigma code. The various sections at Bletchley were kept separated to enhance security.

But more significantly, The Imitation Game shows Turing realisng that Cairncross was passing on Enigma secrets to Moscow. However, according to the movie, Turing didn't reveal the espionage because Cairncross threatened to reveal Turing's homosexuality. Thus as Axel von Tunzelmann notes, the movie makes Turing a traitor. It also clumsily recycles traditional accusations that homosexuals were inherently a security risk.

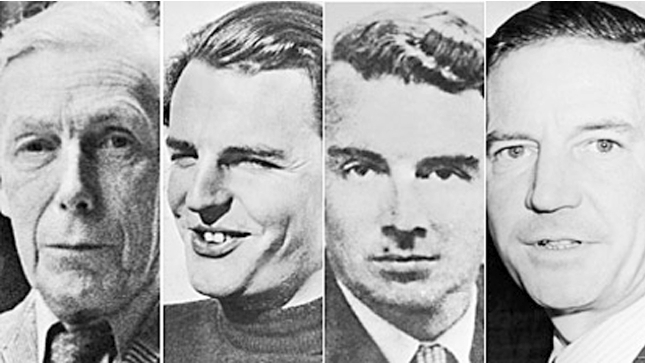

Cairncross was the most obscure of the infamous "Cambridge five": graduates of Cambridge University who worked for the NKVD and passed on British and American secrets to Moscow. during and after World War 2. He still remains overshadowed by his fellow Cambridge spies: Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt, Donald Maclean and Kim Philby, along with Victor Rothschild. Blunt and Burgess , both scions of the English upper class, plus Cairncross ( who was a working-class Scot) belonged to a university secret society known as the Cambridge Apostles, which met Saturday evenings for esoteric debates. after eating sardines on toast and drinkinbg coffee. The Apostles, founded in 1820, was so-called because its twelve original members claimed to be the twelve most intelligent people at Cambridge.

Alan Turing also went to Cambridge from 1931 to 1934, gaining a first class degree in Mathematics. He never belonged to the Apostles, nor is it likley that he ever met any of the Cambridge spies.

But more significantly, The Imitation Game shows Turing realisng that Cairncross was passing on Enigma secrets to Moscow. However, according to the movie, Turing didn't reveal the espionage because Cairncross threatened to reveal Turing's homosexuality. Thus as Axel von Tunzelmann notes, the movie makes Turing a traitor. It also clumsily recycles traditional accusations that homosexuals were inherently a security risk.

Cairncross was the most obscure of the infamous "Cambridge five": graduates of Cambridge University who worked for the NKVD and passed on British and American secrets to Moscow. during and after World War 2. He still remains overshadowed by his fellow Cambridge spies: Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt, Donald Maclean and Kim Philby, along with Victor Rothschild. Blunt and Burgess , both scions of the English upper class, plus Cairncross ( who was a working-class Scot) belonged to a university secret society known as the Cambridge Apostles, which met Saturday evenings for esoteric debates. after eating sardines on toast and drinkinbg coffee. The Apostles, founded in 1820, was so-called because its twelve original members claimed to be the twelve most intelligent people at Cambridge.

Alan Turing also went to Cambridge from 1931 to 1934, gaining a first class degree in Mathematics. He never belonged to the Apostles, nor is it likley that he ever met any of the Cambridge spies.

|

John Cairncross was the odd man out in the Cambridge spy network. He lacked the privileged social upbringing and status of the others, as well as their patrician assurance and social contacts. Born in 1913 in Lanarkshire, Scotland his father was an ironmonger and his mother a teacher. He did not go to an elite 'public' school where his academic ability won him a scholarship to the unfashionable (but excellent) Glasgow University. He then studied at the Sorbonne and in 1934 went to Cambridge to further his studies in German and French.

In terms of academic accomplishment he was miles ahead of the other Cambridge spies. But his broad Scots accent, red hair, rather bad-tempered personality and lack of social graces distinguished him from most of his contemporaries at Cambridge. But in his second year there (1935) he started to attend Communist Party meetings, and was noticed for his bitter anti-Establishment outbursts and knowledge of Marxist rhetoric. AS his later Russian 'minders' commented , Cairncross had a "sizeable chip on his shoulder" and was "a wretched hand at making friends". He regarded Blunt and company as privileged members of an effete social class that deserved to be overthrown. But he gained top marks in the Foreign Office's prestigious entrance examinations and joined that institution, where he was recruited by Jack Klugman, another Cambridge grad who worked for the NKVD. At the start of the war he was promoted to the Cabinet Office, which gave him access to top secret Cabinet papers. He passed the contents of many of these on to his Soviet handlers. They included a key document on Britain's ability to build an atomic bomb. When he went to work at Bletchley as a translator, Cairncross smuggled out Enigma transcripts, sometimes in his trousers, transferred them into a bag at the local railway station and handed them over to his Soviet handlers in London. |

Cairncross always indignantly denied that he was a traitor. In his self-serving autobiography The Enigma Spy, he claimed "i have no reason to feel ashamed of anything I haver done. I never worked for the enemy, but for a potential or actual ally .... And I do not feel I have reason to regret my actions since I never sold information at any time to anyone.”