The Imitation Game (2014)

What's the link between The Imitation Game and Blade Runner ?

The Imitation Game 's title refers to a famous test devised by Alan Turing, the movie's real-life hero. In 1950 Turing, one of the leading pioneers of artificial intelligence, suggested a 'game' or test that could be used to decide if a computer program was able to imitate human conversation so that convincingly that humans interacting with it could not tell if they were 'conversing' with an artificial machine. If the human believes the programme to be a person then the programme has won the game. Essentially, the computer has proved itself capable of imitating human thought so convincingly that its human interviewer belives that he or she is in contact with a human not a machine. Another explanation of Turing's test was that if an expert can't tell the difference between human intelligence responses and a computer's responses than the computer has genuine human intelligence.

However, this argument is no longer accepted by most artificial intelligence experts and philosophers. As Turing himself realised, there is a problem with his imitation game. It is testing the computer program's ability to imitate human reasoning rather than proving whether or not it is actually 'thinking' for itself , i.e. displaying true intelligence.If the computer wins the game, it's shown that it can successfully imitate human thought, not that it has developed true intelligence artificially.

However, this argument is no longer accepted by most artificial intelligence experts and philosophers. As Turing himself realised, there is a problem with his imitation game. It is testing the computer program's ability to imitate human reasoning rather than proving whether or not it is actually 'thinking' for itself , i.e. displaying true intelligence.If the computer wins the game, it's shown that it can successfully imitate human thought, not that it has developed true intelligence artificially.

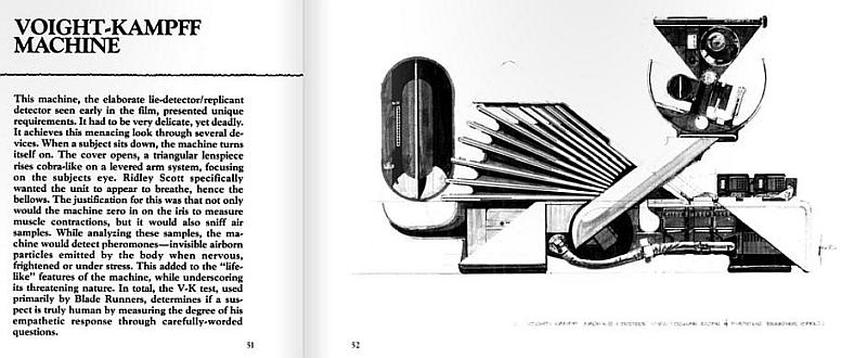

The imitation game is excitingly referenced in Ridley Scott's classic movie Blade Runner. An early sequence shows a "Voight-Kampff" machine testing a suspect to ascertain if he is a human or an A-I 'replicant by measuring his emphatic response to a series of questions and statements. See what happens.

Who invented the Enigma machine?

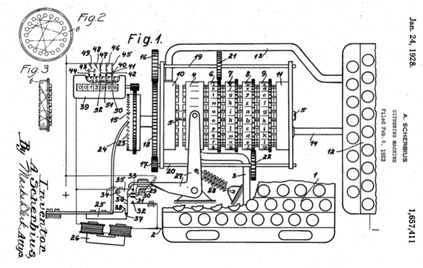

The Enigma machine was indeed invented by Germans, but for commercial rather than military purposes. It was originally designed to protect business and proprietary commercial secrets rather than military ones. Its inventor was a forty year-old German, electrical engineer Arthur Scherbius, who also invented an electric pillow and ceramic heaters. Scherbius's interest in electrical-mechanical rotor machines led him to patent his device in 1918-19. He hoped that its ability to transcribe and transmit coded information would appeal to commercial firms eager to protect their commercial secrets from competitors. After buying the rights to another rotor-encoder developed by Dutch inventor Hugo Koch, Scherbius set up his own company to produce the Enigma.

The machine was displayed publicly at an international postal conference in Switzerland in 1923 and was openly available for purchase by any company (or nation). In 1926 Enigma was first used by the German navy, followed by the army two years later and then the Luftwaffe in 1933. It was also used by various German government departments, such as the railways, as well as by commercial firms.

Scherbius, who was killed in an accident in 1929, does not appear to have made a great deal of money from his invention.

The machine was displayed publicly at an international postal conference in Switzerland in 1923 and was openly available for purchase by any company (or nation). In 1926 Enigma was first used by the German navy, followed by the army two years later and then the Luftwaffe in 1933. It was also used by various German government departments, such as the railways, as well as by commercial firms.

Scherbius, who was killed in an accident in 1929, does not appear to have made a great deal of money from his invention.

The crucial Polish Contribution to unveiling Enigma's secrets

During the 1920s and 1930s Poland had a number of brilliant mathematicians, some of whom were also outstanding cryptologists employed in the Polish government's Biuro Szyfrow (Cipher Bureau). By the mid-1920s, the government correctly suspected that Germany was already flouting the Versailles Treaty by secretly re-arming. The Biuro Szyfrow monitored German military radio channels and suspected that an extremely sophisticated German device was encoding messages. When an Enigma machine was sent to Poland by mistake the consequent German uproar alerted the Poles, and the Cipher Bureau examined it. They then coolly ordered a commercial machine from its German manufacturer and, years before Bletchley Park, set about trying to figure out how Enigma worked. The Bureau used the services of some remarkable students from the University of Poznan's Mathematics renowned department. These included the trio of Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Rozycki and Henrik Zygalski. The Enigma investigations were helped by the French, who gave the Bureau key documents stolen by Hans-Thilo Schmidt, a German cipher clerk.

The Bureau was able to decipher German Enigma code from 1933. When Goering visited Warsaw in 1934, the Bureau were able to decipher his person encoded correspondence. British codebreakers had unable to break the code. However, despite the increasing evidence of Hitler's expansionist intentions,especially towards Poland, it wasn't until a few weeks before war broke out in 1939 that the Poles belatedly used their Enigma knowledge to gain British and French support. The head of Polish Intelligence asked the British and French to meet him. He informed the small delegation (including the astonished head of M.I.6) that the Poles had broken Enigma. The Poles gave the British and French details of ciphers and two replicas of the Enigma machine made by the Bureau. One replica went to England by way of diplomatic bag; the other was transported there in a bag carried by the French film and stage star Sacha Guitry (who was later suspected of collaboration).

Hitler's troops invaded Poland on 1 September, a fortnight after the replicas arrived in England. On 17 September, the day Russia invaded Poland, Zygalski, Rejewski and Rozycki fled their homeland and worked with a French cryptographic team until the fall of France in June, 1940. Eventually Zygalski and Rejewski ( Rozycki drowned in 1942 when his ship was sunk in the Mediterranean) reached Portugal by way of Algeria and Spain. The two made it to England, but apparently did not work at Bletchley Park but in a small Polish office near London. Unfortunately, this suspiciously strange arrangement meant that the Polish contribution to the Enigma decoding remained unknown for years after the British claimed credit in the 1980s. Understandably, this situation was resented by the Poles who eventually built their own memorial to the three men. It took half a century for the British to officially acknowledge the Poles' invaluable contribution to breaking Enigma.

Hitler's troops invaded Poland on 1 September, a fortnight after the replicas arrived in England. On 17 September, the day Russia invaded Poland, Zygalski, Rejewski and Rozycki fled their homeland and worked with a French cryptographic team until the fall of France in June, 1940. Eventually Zygalski and Rejewski ( Rozycki drowned in 1942 when his ship was sunk in the Mediterranean) reached Portugal by way of Algeria and Spain. The two made it to England, but apparently did not work at Bletchley Park but in a small Polish office near London. Unfortunately, this suspiciously strange arrangement meant that the Polish contribution to the Enigma decoding remained unknown for years after the British claimed credit in the 1980s. Understandably, this situation was resented by the Poles who eventually built their own memorial to the three men. It took half a century for the British to officially acknowledge the Poles' invaluable contribution to breaking Enigma.

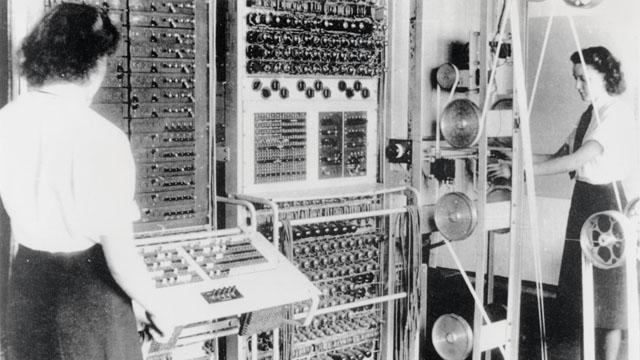

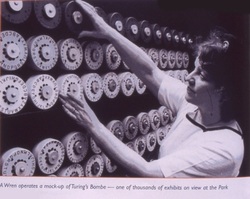

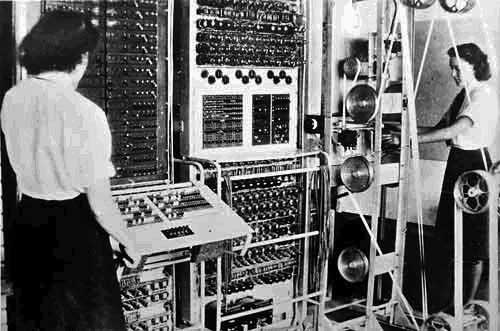

The role of Bletchley Park's women in helping break Enigma

One of the most interesting features of the Bletchley Park codebreakers is the significant contribution that women made in the struggle to decipher the German military codes during the war. Indeed, women made up about 80 per cent of Bletchley's work force. Most were stenographers, typistes and secretaries whose work was classified and who frequently worked round the clock in cramped conditions.

The Imitation Game suggests that only one woman - Joan Clarke - worked with Turing and his team on breaking Enigma. In fact, several women worked at Bletchley as top codebreakers. For example, Margaret Rock was a brilliant mathematician and statistician who joined Bletchley when she was in her mid-thirties, rather older than most of the women who were employed straight from school or university. A few of the women were expert linguists, like Mavis Batey The most famous of these was Mavis Batey, who was only nineteen when she began working there. Her expertise was in German language and literature, not mathematics, and she originally intended to become a nurse.

But the authorities had other ideas and recommended her for espionage work. Her initial reaction was interesting:

“So I thought, great,” she recalled. “This is going to be an interesting job, Mata Hari, seducing Prussian officers. But I don’t think either my legs or my German were good enough because they sent me to the Government Code & Cipher School.”

From there she went to Bletchley. One of her first tasks was to read personal ads in newspapers to search for enemy coded messages. Soon she was assigned to work under Margaret Rock and Dillys (Dilly) Knox, one of Bletchley's leading codebreakers.

The Imitation Game suggests that only one woman - Joan Clarke - worked with Turing and his team on breaking Enigma. In fact, several women worked at Bletchley as top codebreakers. For example, Margaret Rock was a brilliant mathematician and statistician who joined Bletchley when she was in her mid-thirties, rather older than most of the women who were employed straight from school or university. A few of the women were expert linguists, like Mavis Batey The most famous of these was Mavis Batey, who was only nineteen when she began working there. Her expertise was in German language and literature, not mathematics, and she originally intended to become a nurse.

But the authorities had other ideas and recommended her for espionage work. Her initial reaction was interesting:

“So I thought, great,” she recalled. “This is going to be an interesting job, Mata Hari, seducing Prussian officers. But I don’t think either my legs or my German were good enough because they sent me to the Government Code & Cipher School.”

From there she went to Bletchley. One of her first tasks was to read personal ads in newspapers to search for enemy coded messages. Soon she was assigned to work under Margaret Rock and Dillys (Dilly) Knox, one of Bletchley's leading codebreakers.

Although only nineteen, Mavis played a key role in helping break the Italian Navy's version of the Enigma Code. Batey discovered a flaw in the Italian machine's wiring system that enabled the Bletchley team to decode the system. This enabled the British Navy's Mediterranean fleet to ambush the Italians in a major fleet action action, sinking three cruisers and two destroyers. Later, working with Margaret Rock, Batey broke some of the secrets of the German Abwehr [secret service] Enigma code. It took several decades after the war ended before Batey felt able to even reveal that she had worked at Bletchley, let alone discuss her exploits -the secrecy agreement all Bletchley workers signed forbade any mention of their activities for 50 years.

Several other women also played leading roles in the Bletchley code-breaking team. These included Margaret Rock (above left), whose credentials were in mathematics and statistics, and who along with Batey helped discover the secrets of the Abwehr Enigma code. The young Welshwoman Mair Thomas's academic background was in music and German. Instead of becoming a professional pianist she was recruited for Bletchley,ending up working alongside Rock and Batey in Huts 6 and 8. Her reminiscences of her time at Bletchley, My Secret Life in Hut Six, are light on technical details but valuable for their insights into her strong religious beliefs and the difficulties -social and personal - of working under such high pressure for long hours in confined conditions.

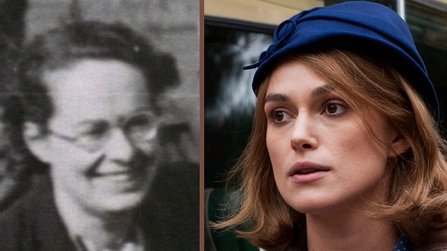

Joan Clarke: Portrayed by Kara Knightley in The Imitation Game

Joan Clarke, like her mentor 'Dilly' Knox (below) came from a a family with a religious background -her father was a minister. She was a brilliant student of Mathematics at Cambridge and this ability led to her recruitment for Bletchley in 1940. Before long she was working with the top code-breakers, including Turing, whom Clarke already knew through his friendship with one of her brothers. The socially awkward couple soon became close friends. Both were brilliant mathematicians and skilled chess players; the pair also shared an interest in Botany. A few days after the two became engaged, Turing informed Clarke of his homsexuality but the engagement continued for some months until Turing ended it because he believed his homosexuality made a viable marriage impossible. The movie correctly portrays the pair remaining close friends until Turing's death.

In real life Clarke was much shyer, hesitant and more introverted than the figure portrayed by Keira Knightley. Nor did she display the fetching dress style depicted in the movie: the war years and the immediate postwar era was a time of austerity and rationing of food and clothing.Only the rich (and Clarke was certainly not wealthy) had the means and influence to afford or obtain the fashionable items the movie's clothing designers have given Knightley. (The Joan Clarke -like character in Enigma has been provided with a much more accurate wardrobe).

The Imitation Game has other inaccuracies about the Clarke-Turing relationships. Her parents already knew him from his friendship with Clarke's brother. The couple did not make public their engagement; it was kept a secret from the Bletchley team.

In real life Clarke was much shyer, hesitant and more introverted than the figure portrayed by Keira Knightley. Nor did she display the fetching dress style depicted in the movie: the war years and the immediate postwar era was a time of austerity and rationing of food and clothing.Only the rich (and Clarke was certainly not wealthy) had the means and influence to afford or obtain the fashionable items the movie's clothing designers have given Knightley. (The Joan Clarke -like character in Enigma has been provided with a much more accurate wardrobe).

The Imitation Game has other inaccuracies about the Clarke-Turing relationships. Her parents already knew him from his friendship with Clarke's brother. The couple did not make public their engagement; it was kept a secret from the Bletchley team.

'Dilly' Knox and the Bletchley Park Codebreakers

The fact that were so many women codebreakers at work in the legendary Hut 6 of Bletchley Park was largely due to one man: the legendary Arthur Dilwyn Knox, better known as 'Dilly'. His family connections and friendships were remarkable His father was Bishop of Manchester, one of his brothers was the famous theologian Ronald Knox, and his niece was the novelist Penelope Fitzgerald. His friends included J.M. Keynes. He was a brilliant Classics scholar who was a world authority on deciphering ancient Egyptian papyri. This modest and self-effacing man combined his fascination with the ancient world with an interest in logic, mathematics and the works of Lewis Carroll.

From World War I until his death in 1943, Knox was Britain's leading codebreaker. He was one of the trio sent to Warsaw in July,1939 to meet with Polish and French codebreakers at the Bureau Szyfrow, where the Poles demonstrated how their cloned Enigma machine and how, until recently, they had managed to crack 75% of the German coded messages. Knox was infuriated that the Poles had beaten the British -although the Poles admitted that recent German innovations to Enigma were proving difficult to overcome. But the Poles also provided Knox with their insight into the how the machine's encipherment mechanism was wired. None of the British codebreakers, including Turing and Knox, had worked this out.

He soon became a crucial figure leading Bletchley's campaign to crack Enigma. Perhaps his major contribution was his ability to locate codebreaking talent (especially female talent) and provide the encouragement and leadership that enabled his disparate team in the famous Hut 6 to successfully experiment and innovate. Although Knox belonged to the older 'linguistic' school of codebreakers, once he had seen what the Polish mathematical codebreakers had achieved, he fostered the growth of the English 'mathematical' school of codebreakers (especially Alan Turing) provided many of the essential breakthroughs. It was Knox who initially supervised the work of Turing and his fellow mathematicians Peter Twinn and John Jeffreys at Bletchley.

From World War I until his death in 1943, Knox was Britain's leading codebreaker. He was one of the trio sent to Warsaw in July,1939 to meet with Polish and French codebreakers at the Bureau Szyfrow, where the Poles demonstrated how their cloned Enigma machine and how, until recently, they had managed to crack 75% of the German coded messages. Knox was infuriated that the Poles had beaten the British -although the Poles admitted that recent German innovations to Enigma were proving difficult to overcome. But the Poles also provided Knox with their insight into the how the machine's encipherment mechanism was wired. None of the British codebreakers, including Turing and Knox, had worked this out.

He soon became a crucial figure leading Bletchley's campaign to crack Enigma. Perhaps his major contribution was his ability to locate codebreaking talent (especially female talent) and provide the encouragement and leadership that enabled his disparate team in the famous Hut 6 to successfully experiment and innovate. Although Knox belonged to the older 'linguistic' school of codebreakers, once he had seen what the Polish mathematical codebreakers had achieved, he fostered the growth of the English 'mathematical' school of codebreakers (especially Alan Turing) provided many of the essential breakthroughs. It was Knox who initially supervised the work of Turing and his fellow mathematicians Peter Twinn and John Jeffreys at Bletchley.