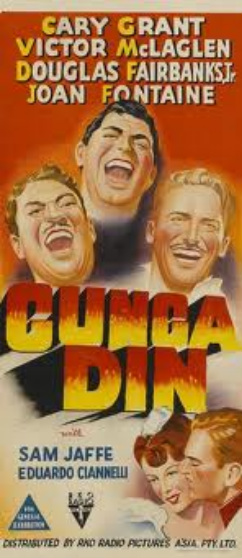

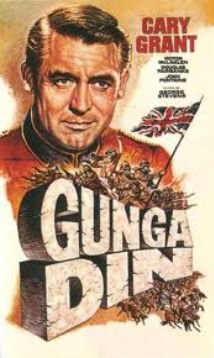

Gunga Din (1939)

|

|

The Director George Stevens, director of 'Gunga Din'.

George Stevens was one of the most meticulous and painstaking of Hollywood directors. During his long career, stretching from Laurel and Hardy comedies to the 1960s, he showed mastery of an amazing variety of genres. In Gunga Din he made one of the great Hollywood action films, while Shane is one of the greatest of all westerns.He also made musicals, comedies, romances and tragic dramas.Stevens became famous for his insistence on filming a scene from every possible angle until he was completely satisfied its artistic potential had been captured on film. He coaxed good performances from actors ranging from Cary Grant, Elizabeth Taylor to James Dean and Shelley Winters.

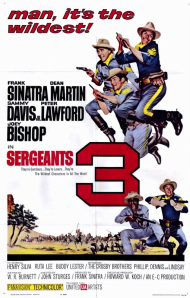

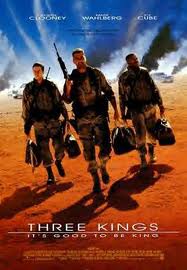

Spielberg's Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom's References to Gunga DinSteven Spielberg pays homage to Gunga Din throughout Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. The former's credit sequence features a large gong; an even larger one is used in the opening nightclub sequence of Spielberg's film. A cute but obstreperous elephant turns up in both films. So does a rope bridge over a chasm. In both films the villains are the Thuggees, a murderous band of natives who kidnap local villagers. Temples and deserted villages also feature in both films, and the leader of the Thuggees in Temple resembles his counterpart in Gunga Din. Both films have also been accused of incorporating racist stereotyping and racist attitudes.

The Thuggees

The Indian cult known as the Thuggees are the designated villains of Gunga Din, Temple of Doom and several other films.Supposedly characterised by their propensity for human sacrifice and murder, the term may originally have been used to mean 'betrayers', the title of an exciting book by John Masters made into a mediocre movie.

Find out more! Gunga Din and 'Empire Cinema'

Gunga Din was of course a Hollywood film, made in the USA, by an American director and crew, and with a largely American cast. Yet it is often cited as an example of 'empire cinema' in its depiction of British India and its peoples and customs.

This term refers to those Hollywood and British films made during the interwar and postwar 20th century, and even later (e.g. Temple of Doom). These films include Gunga Din and The Rains Came (1940), and the British 1938 effort, The Drum a.k.a. Drums. Such films, some critics argue, share a common, stereotyped racial and cultural perspective of India. They also project a favorable view of Britain and the USA in their imperial missions abroad. At the same time they depict an India that is violent, corrupt and divided. Saviours rescuing the 'natives' A benevolent American rescues Indians from savagery.

All these films show the British (and American Indy) as the saviours of either Indian children or child-like adult Indians. They bring order and justice to India and vanquish those Indians who still cling to savage and uncivilised values. Significantly, the Indians lack the intelligence, initiative and courage to protect themselves - a key aspect of empire cinema. Alternately, these views may be seen as the projections of academic and political bias, and an unwillingness to accept that the film-makers were interested maInly in entertaining an audience with dramatic and colourful action, spectacle and dramatic situations, not in issues of race and imperialism.

An interesting variant on the emoire cinema theme is provided by the little-known 1988 Merchant-Ivory production, The Deceivers. While its plot concerns the efforts of an Englishman to infiltrate the Thuggees in order to protect the natives and install respect for British-imposed law and order, this movie also demonstrates the considerable impact of Indian customs and values on westerners., and the psychological turmoil that results. |

About this movie

In Kipling's poem, Gunga Din is a young Indian waterbearer (dhisti) -played by Sam Jaffe, left, in brownface - for a British regiment in northwest India.He is the butt of jokes and pranks by the soldiers,who reject him on racial grounds. Yet the boy wants to be accepted by the soldiers, and his dream is of becoming a soldier in the regiment.When the soldiers have to put down a rising, Gunga Din proves himself to be a brave warrior, dying in order to save one of the regiment. His nobility and courage is contrasted with the racism of his British 'superiors'. After his death he is accepted as one of the regiment and the narrator says "Though I've belted you and I've flayed you, By the living Gawd that made you, You're a better man than I am, Gunga Din".The film's script cleverly combines elements of Kipling's poem with features from a collection of his short stories Soldiers Three about the adventures of three soldiers in the Indian army. In the movie Gunga Din (pictured above) is rather older than Kipling's dhisti of the poem, but he still wants to be accepted by the regiment as a soldier. The film's plot emphasises the various adventures and antics of the three British sergeants stationed near the Khyber Pass. The three friends, played by Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen and Douglas Fairbanks Jr), irreppressible but courageous, accompanied by Gunga Din, are sent on a mission that eventually involves a deserted village, thuggees and their temple, mayhem and acts of heroism.

|

|

|