Thuggees in movies

|

|

Thuggees - the debate:Although the thuggees may seem to be merely exotic villains in movies and novels, their actual historical significance remains a matter of controversy amongst historians. For decades from the early 19th century they were regarded as a bloodthirsty cult of stranglers and robbers whose victims were mainly travellers on Indian roads.Their reign of terror was supposedly ended by the efforts of William Sleeman. This view was best represented by the 20th century historian George Bruce.

Yet this view was challenged during the later 20th century.Its depiction of the Thuggees as murderous thieves and Kali-worshippers was replaced by an insistence that this was just another condescending yet fearful European archetype of native peoples, along with such groups as Assassins, witch-doctors, cannibals and Leopard-men. Thuggees constituted a crude colonial representation, a British invention and a figment of the overwrought colonial imagination, according to Indian historians like Parama Roy. Such views fitted in the Orientalist theory of Edward Said, who argued that westerners of the 19th and 20th centuries imposed a demeaning and rigid template on their representations of eastern culture, society and customs. Indeed, Hiralal Gupta insisted that the thuggees existed as a result of the chaos that he claimed was caused by the East India Company's imperialistic designs on India. Martine van Woerkins argues that British claims about the Thuggees arouse out of their fears and misunderstandings of rural India and its religious and social customs. Others argue that the Thuggees were just a convenient excuse for the British to extend control over native-ruled states of central India. Two British historians have attacked these revisionist arguments. They have actually extensively used the massive reservoir of documentation ignored by Roy and others. Mike Dash's Thug and Kim Wagner's two scholarly books show that some 'popular' views of Thuggees are invalid. These include the claim that they were essentially a religious cult,and that Henry Sleeman was an inspirational figure in the suppression of Thuggees. Wagner notes that campaigns against the group began twenty years before Sleeman. Sleeman was also an early spin-doctor, shrewdly manipulating his image as as protector of the population from the Thuggee threat. Dash and Wagner use documents to show that the Thuggees were not a figment of overheated British imaginations. They were feared by the Indian natives as well, for good reason. Thuggees did rob and kill thousands of locals. Their primary motive was robbery. Their worship of Kali was typical of many Indian criminals at that time. Thuggees were another form of organised crime, like the Mafia, members of a criminal underclass. LIke other other criminal groups in India,and indeed throughout the world, they used various rituals and codes as a means of group identification and protection from infiltration. |

Confessions of a Thug - a crucial book

A crucial factor in the nineteenth century Anglo-American fascination with thuggees was an adventure story written by Philip Meadows Taylor and published in 1839. An indication of its popularity is the fact that the book is still published today; the Oxford University edition has an erudite preface explaining the book's significance.

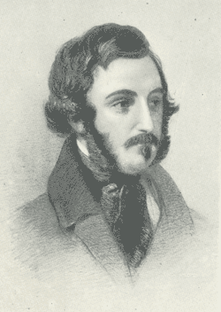

Taylor was born in England and went to India at the age of 16. He eventually became an officer in the private army of the Nizam of Hyderabad, one of India's powerful princely rulers, where he became adept in both Hindi and Persian. He was promoted to the post of Police Superintendent for a troubled part of the Nizam's huge territory. It was here where he found evidence of Thuggee murders and set out to wipe out the band. LIke his better-known contemporary William Sleeman, Taylor did not infiltrate the Thuggees: he used the evidence of captured Thuggees to hunt down and arrest members of the cult.

Unlike Sleeman, Taylor used his knowledge of Thuggees to write fiction. From 1841 he spent a decade as Indian correspondent for the London Times. After the success of Confessions, Taylor wrote several other novels about India, such as Ralph Darnell and Seeta, the latter about a 'mixed' marriage between an Englishman and a Hindu woman. These books further demonstrated his positive and sympathetic attitude towards India and its native inhabitants. He was a skilled botanist and artist: his visual records of Indian flora and artefacts are regarded as invaluable today and are to be found in numerous museums.

His 1839 novel Confessions of a Thug was a best-seller. The young Queen Victoria demanded to read the proofs before it was published; the youthful Mark Twain enjoyed it and praised it decades later.[Kevin Rushby, "Imperial Deceivers", Guardian, 18 January, 2003]. Readers of the Victorian age loved its exotic settings, portraits of a secret society, gory details, and the many scenes of murder, conspiracy and betrayal. But Confessions is much more than a Victorian potboiler. Taylor writes with obvious background knowledge combined with a sympathetic attitude towards India and Indians (he was married to a Eurasian woman). He does not adopt the conventional condescending and patronising attitudes of the British towards the customs and rituals of the sub-continent. Nor does his novel indulge in pious platitudes about ungodly and savage habits of the heathen.

Surprisingly, the hero of Confessions of a Thug is not British at all. He is a native Indian Muslim, Ameer Ali, who is himself a thug and the book details his rise in the gang, not with outrage and abhorrence, but with a fascinated, essentially amoral, zeal. It's a bit like The Godfather's Don Corleone or George McDonald Fraser's 'hero' Flashman. And Ameer - killer, womaniser, thief, scoundrel, unremorseful - comes across not as a despicable villain, but as a resourceful, clever person, proud, courageous, a kind if not faithful husband and benevolent father. In fact, Ameer comes across as a likeable rogue. He punishes corrupt officials, has an eye for pretty women and rescues some of them from fates worse than death, looks after widows and orphans. His fellow thuggees are also presented surprisingly favourably; they murder and rob, but they do not torture or rape, like non-thuggee criminals in the book, and they practise religious toleration.

Taylor was born in England and went to India at the age of 16. He eventually became an officer in the private army of the Nizam of Hyderabad, one of India's powerful princely rulers, where he became adept in both Hindi and Persian. He was promoted to the post of Police Superintendent for a troubled part of the Nizam's huge territory. It was here where he found evidence of Thuggee murders and set out to wipe out the band. LIke his better-known contemporary William Sleeman, Taylor did not infiltrate the Thuggees: he used the evidence of captured Thuggees to hunt down and arrest members of the cult.

Unlike Sleeman, Taylor used his knowledge of Thuggees to write fiction. From 1841 he spent a decade as Indian correspondent for the London Times. After the success of Confessions, Taylor wrote several other novels about India, such as Ralph Darnell and Seeta, the latter about a 'mixed' marriage between an Englishman and a Hindu woman. These books further demonstrated his positive and sympathetic attitude towards India and its native inhabitants. He was a skilled botanist and artist: his visual records of Indian flora and artefacts are regarded as invaluable today and are to be found in numerous museums.

His 1839 novel Confessions of a Thug was a best-seller. The young Queen Victoria demanded to read the proofs before it was published; the youthful Mark Twain enjoyed it and praised it decades later.[Kevin Rushby, "Imperial Deceivers", Guardian, 18 January, 2003]. Readers of the Victorian age loved its exotic settings, portraits of a secret society, gory details, and the many scenes of murder, conspiracy and betrayal. But Confessions is much more than a Victorian potboiler. Taylor writes with obvious background knowledge combined with a sympathetic attitude towards India and Indians (he was married to a Eurasian woman). He does not adopt the conventional condescending and patronising attitudes of the British towards the customs and rituals of the sub-continent. Nor does his novel indulge in pious platitudes about ungodly and savage habits of the heathen.

Surprisingly, the hero of Confessions of a Thug is not British at all. He is a native Indian Muslim, Ameer Ali, who is himself a thug and the book details his rise in the gang, not with outrage and abhorrence, but with a fascinated, essentially amoral, zeal. It's a bit like The Godfather's Don Corleone or George McDonald Fraser's 'hero' Flashman. And Ameer - killer, womaniser, thief, scoundrel, unremorseful - comes across not as a despicable villain, but as a resourceful, clever person, proud, courageous, a kind if not faithful husband and benevolent father. In fact, Ameer comes across as a likeable rogue. He punishes corrupt officials, has an eye for pretty women and rescues some of them from fates worse than death, looks after widows and orphans. His fellow thuggees are also presented surprisingly favourably; they murder and rob, but they do not torture or rape, like non-thuggee criminals in the book, and they practise religious toleration.

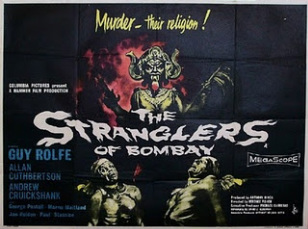

Hammer Horror Movie - 'Stranglers of Bomba' |

'Temple of Doom' - the notorious Thuggee temple scene |