Woman in Gold: the Viennese Background

"I have an indomitable affection for Vienna but I know her abyss" - Sigmund Freud

“Here the battle raged: about the unconscious, about dreams, about new music, the new way of seeing, the new architecture, the new logic, the new morality.” - Stefan Zweig

“Here the battle raged: about the unconscious, about dreams, about new music, the new way of seeing, the new architecture, the new logic, the new morality.” - Stefan Zweig

|

In those first 14 years of the 20th century, Vienna, more than anywhere else, was the fulminating, bewitching crucible where the modern world was invented .... There have been artistic and social upheavals in other cities at various times – Paris, London, New York and Berlin have all been the cynosure of cultural movements – but was there ever such a concentration of genius across the broad spectrum of thought and culture that could be found in Vienna and the Austro-Hungarian empire during those early years of the 20th century? If we start drawing up some lists of names the idea appears ever more plausible. In literature: Rilke, Kafka, Roth, Musil, Zweig, Schnitzler. Music: Mahler, Schoenberg, Webern, Berg. Architecture: Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos. Painting: Klimt, Schiele and Kokoschka. Philosophy: Wittgenstein and the origins of the Vienna Circle school. Journalism: Karl Kraus. The brew is almost too rich. Then throw in Adolf Hitler and, of course, the sine qua non, Sigmund Freud. William Boyd, "Oh, Vienna", Guardian 3/2/2012 |

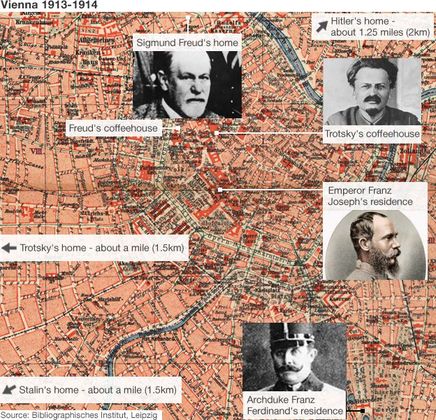

In the first decade and a half of twentieth Century Vienna, the city's cultural influences were unsurpassed in Europe. Gutsav Klimt and Adele and Fredrich Bloch-Bauer were participants in the new century's most fervent and invigorating intellectual milieu. "Here the battle raged," exclaimed the novelist Stefan Zweig, "about the unconscious, about dreams, about new music, the new way of seeing, the new architecture, the new logic, the new morality.” The city was a cultural pioneer of the new century, fomenting an invigorating intellectual atmosphere in which great minds and talents luxuriated. Young men who would later become famous (or infamous in some cases) for their politics spent some time in pre-war Vienna - notably Hitler, but also Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin,and the future dictator of Yugoslavia, Josep Broz (Tito). The latter worked in the Daimler car factory near the city . And NIkolai Bukharin, one of the leading Marxists (later to be a an important member of the Soviet regime) spent some years in Vienna where he write seminal articles on Marxist economic theory. In fact, Lenin briefly visited Bukharin there in June 1913. That year also saw Bukharin help Stalin with the future dictator's Marxism and the National Question, an article that gave him considerable status within the Bolshevik circle and earned him the valuable approval of Lenin.

It's quite possible that for a few weeks in 1913, Hitler, Freud, Trotsky, Bukharin may have passed each other as they, like many Viennese, walked along the city's famous 'RingRoad' [Ringstrasse] - and in turn been overtaken by Emperor Franz-Josef's carriage on its almost daily journey along the famous boulevard. His nephew and heir Franz-Ferdinand, whose assassination a year later triggered the first workd war, may also have been driven past Hitler, and the others as they each walked along the boulevard.

It's quite possible that for a few weeks in 1913, Hitler, Freud, Trotsky, Bukharin may have passed each other as they, like many Viennese, walked along the city's famous 'RingRoad' [Ringstrasse] - and in turn been overtaken by Emperor Franz-Josef's carriage on its almost daily journey along the famous boulevard. His nephew and heir Franz-Ferdinand, whose assassination a year later triggered the first workd war, may also have been driven past Hitler, and the others as they each walked along the boulevard.

Another connection between the disparate figures of Hitler, Stalin, Freud, Trotsky and Bukharin (and the artist Gustav Klimt) was their participation in one of early twentieth Century Vienna's most famous and widespread social and intellectual features - the city's legendary coffeehouse culture. By 1900 there were at least 600 coffee houses in Vienna. In 1913 Cafe Central was attended by Hitler, Lenin, Trotsky and Josip Broz Tito.

The Austrian author Stefan Zweig believed the Viennese coffee house to be an essential part of the cuty's rich cosmopolitan atmosphere, a creative meeting placeof artistic, cultural and political discussion. For Zwig it was "a sort of democratic club, open to everyone for the price of a cheap cup of coffee, where every guest can sit for hours with this little offering, to talk, write, play cards, receive post, and above all consume an unlimited number of newspapers and journals." Not only did the coffeehouses provide warmth in winter, shade in summer and a place to sit and relax or write, argue, compose and sketch - all day and all for the price of one coffee. They were open to the lonely and impoverished, like Hitler, and to the wealthy and gregarious, like Klimt, and to those who wanted to display their sartorial elegance (like the young Tito).

A list of the individuals frequenting the coffee houses reads like a Who's Who of the early 20th century. In the arts the most significant establishment was Café Museum, whose regular guests included Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka (and, in music, the composer Alban Berg).

The Austrian author Stefan Zweig believed the Viennese coffee house to be an essential part of the cuty's rich cosmopolitan atmosphere, a creative meeting placeof artistic, cultural and political discussion. For Zwig it was "a sort of democratic club, open to everyone for the price of a cheap cup of coffee, where every guest can sit for hours with this little offering, to talk, write, play cards, receive post, and above all consume an unlimited number of newspapers and journals." Not only did the coffeehouses provide warmth in winter, shade in summer and a place to sit and relax or write, argue, compose and sketch - all day and all for the price of one coffee. They were open to the lonely and impoverished, like Hitler, and to the wealthy and gregarious, like Klimt, and to those who wanted to display their sartorial elegance (like the young Tito).

A list of the individuals frequenting the coffee houses reads like a Who's Who of the early 20th century. In the arts the most significant establishment was Café Museum, whose regular guests included Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka (and, in music, the composer Alban Berg).

A key reason for the city's cultural vibrancy was its role as the capital of the enormous, strategically placed but potentially unstable Austrian-Hungarian empire. The map below left shows both the enormous size of the empire and its dominating strategic location in Europe. The wide range of different ethnicties (excluding Jews) and territorial divisions that made up that Empire is reflected in the map below right. This rich and variegated social, racial, political and religious mix stimulated cross-cultural fertilisation

Vienna's tremendous economic growth in recent decades (tempered by increasing levels of poverty, social inequality and disease) had in recent decades attracted a flood of new arrivals from the various races and regions of the far-flung empire. By 1900 the city numbered at least two million, only half of whom had been born in Vienna . It reflected the astounding ethic and cultural diversity of the empire, indicating Vienna's role as the crossroads of eat and west Europe. Austria-Hungary had no fewer than eleven official nationalities and even more 'unofficial' ones. Army officers, for example, had to give commands in German and eleven other languages. All these groups, with their twelve national anthems, and competing cultural, political and racial agendas, were to be found in Vienna. Yet the national and racial groups in the Austrian (western) segment of the empire had the remarkable security of clause nineteen of the National Constitution, which proclaimed that " all ethnic groups ... have equal rights and ... an inalienable right to preserve and cultivate its nationality and language." The venerable Emperor Franz Josef had personally guaranteed this law.

Vienna's tremendous economic growth in recent decades (tempered by increasing levels of poverty, social inequality and disease) had in recent decades attracted a flood of new arrivals from the various races and regions of the far-flung empire. By 1900 the city numbered at least two million, only half of whom had been born in Vienna . It reflected the astounding ethic and cultural diversity of the empire, indicating Vienna's role as the crossroads of eat and west Europe. Austria-Hungary had no fewer than eleven official nationalities and even more 'unofficial' ones. Army officers, for example, had to give commands in German and eleven other languages. All these groups, with their twelve national anthems, and competing cultural, political and racial agendas, were to be found in Vienna. Yet the national and racial groups in the Austrian (western) segment of the empire had the remarkable security of clause nineteen of the National Constitution, which proclaimed that " all ethnic groups ... have equal rights and ... an inalienable right to preserve and cultivate its nationality and language." The venerable Emperor Franz Josef had personally guaranteed this law.

Jews were among the main immigrants hoping to take advantage of the official liberal attitude towards minorities. The historian of Hitler's time in pre-war Vienna, Brigette Hamann, notes that "minorities that had been disadvantaged for centuries ... were grateful for having equal rights and therefore were loyal to the state. The Jews particularly looked at strict constitutionality as a safe haven." Hamann, Hitler's Vienna: a Dictator's Apprenticeship (New York:1999), p.91

By 1900 many Jewish families were among Vienna's growing and influential bourgeoisie. Some of them, including the Bloch-Bauers, made their social reputation as patrons of the arts, establishing salons, befriending artists and musicians and commissioning paintings and compositions.

By the early 1900s Jews like the Bloch-Bauers numbered ten per cent of Vienna's population. Their cultural, professional and economic importance was highly significant. A majority of Vienna's doctors and lawyers were Jews. The world-famous Vienna School of Medicine in the early 1900s included two Jewish Nobel Prize winners in Medicine - Karl Landsteiner (who discivered blood groups) and the physiologist Robert Barany.

By 1900 many Jewish families were among Vienna's growing and influential bourgeoisie. Some of them, including the Bloch-Bauers, made their social reputation as patrons of the arts, establishing salons, befriending artists and musicians and commissioning paintings and compositions.

By the early 1900s Jews like the Bloch-Bauers numbered ten per cent of Vienna's population. Their cultural, professional and economic importance was highly significant. A majority of Vienna's doctors and lawyers were Jews. The world-famous Vienna School of Medicine in the early 1900s included two Jewish Nobel Prize winners in Medicine - Karl Landsteiner (who discivered blood groups) and the physiologist Robert Barany.

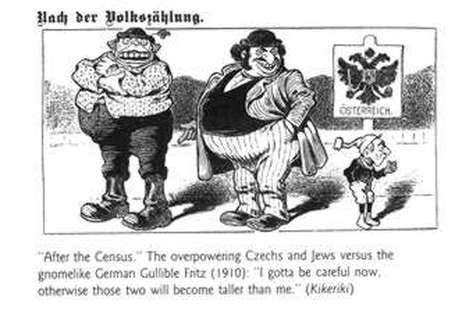

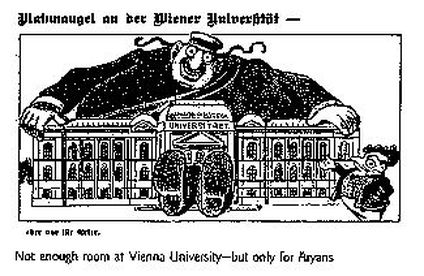

By 1910 two-fifths of Vienna's Jews were merchants and 3.5% industrialists, with another 11.3 % self-employed. Their role in Vienna's banking and commerce was crucial to the city's entreprenerial progress. The city's high schools and universities also included a high proportion of Jewish students. About 40-50% of places in Vienna's top schools for girls were held by teenage Jewish girls. But the disproportional success of Vienna's Jewish population, especially their domination of entrepreurial and professional occupations, and their educational achievements inevitably aroused jealousies and resentment, which became increasingly vocal and strident from the 1890s. By 1900 Vienna was home to an increasing number of stridently anti-semitic groups. Indeed, from 1897 to the start of the war the city was controlled by the Christian Social Party, whose leader, Karl Lueger, was an unscrupulous anti-semitic demagogue. As the two cartoons above reveal, Jews, Czechs (and other minority groups) wete portrayed as privileged and threatening grotesques, supposedly threatening the existence of 'native' Viennese.