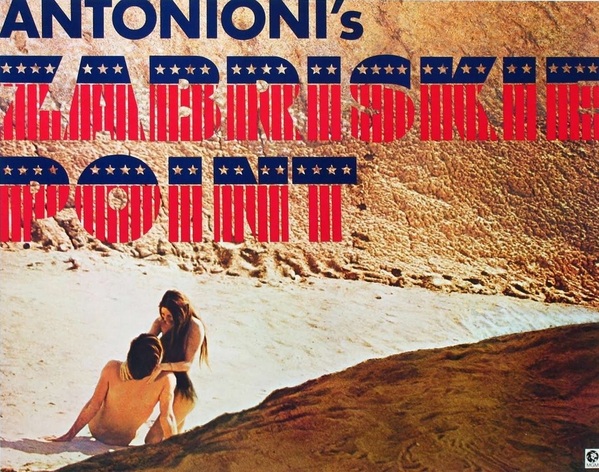

Antonioni's Zabriskie Point and the American Counterculture of the 1960s

Zabriskie Point (1970): the Background

During 1967-8, the director Michaelangelo Antonioni, spent several months in the USA. His most recent film, Blow-up, a study of "swinging London", had been a box-office and critical success for MGM. That studio hoped that Antonionni would make a film about the American counter culture, which in 1967 was at its peak of media attention and popular and political interest. Studio moguls were even prepared to overlook Antonioni's intellectually trendy if rather vague left-wing political views as well as his perfectionist insistence on filming countless takes and obsession with repainting and remodelling entire streets, buildings and interiors (and even natural objects like grass) on location shoots. Antonioni's disdain for conventional narrative and coherent plot was also ignored in MGM's naive hope that the commercial success that followed Blow-up 's combination of nudity, sex, drugs, fashion, youth and murder might be repeated in the director's take on the American counterculture. What MGM's bosses overlooked was that ultimately Blow-up was a mordant condemnation of an amoral, effete, uncaring and directionless section of society. Antonioni's great movie condemned rather than endorsed the values of "swinging London" and it depicted the younger generation as shiftless and shallow.

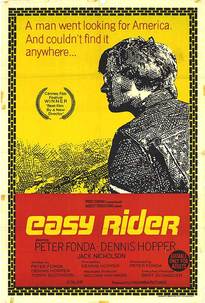

In the late 1960s and early 1970s Hollywood belatedly acknowledged the existence of the counter culture movement, a social and cultural phemonenon usually signified by words such as "hippies" , "communes", "flower power" and "free love". This recognition was no doubt assisted by the box-office success of Easy Rider (1969), one of the most significant of American postwar movies. Easy Rider has become the iconic counter culture movie. Not only did this cheaply-produced film make a lot of money; it was the focus of public and media controversy. Newspapers, politicians, TV pundits, 'experts' on American culture and history, indignant members of the public, delighted radicals excitedly contributed to the controversy about hippies, drugs, violence and the future of America that Easy Rider engendered.

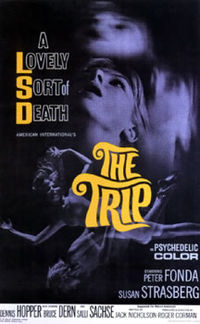

It is commonly assumed that Easy Rider was the first of the counterculture movies. But such films had been made since 1996-7. One of the first and most influential was Roger Corman's 1967 The Trip, which made a good profit in the USA starred Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper and was scripted by Jack Nicholson - the trio responsible for Easy Rider two years later. The 1967 film's LSD hallucinatory sequences were more convincing than those depicted in Easy Rider.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s Hollywood belatedly acknowledged the existence of the counter culture movement, a social and cultural phemonenon usually signified by words such as "hippies" , "communes", "flower power" and "free love". This recognition was no doubt assisted by the box-office success of Easy Rider (1969), one of the most significant of American postwar movies. Easy Rider has become the iconic counter culture movie. Not only did this cheaply-produced film make a lot of money; it was the focus of public and media controversy. Newspapers, politicians, TV pundits, 'experts' on American culture and history, indignant members of the public, delighted radicals excitedly contributed to the controversy about hippies, drugs, violence and the future of America that Easy Rider engendered.

It is commonly assumed that Easy Rider was the first of the counterculture movies. But such films had been made since 1996-7. One of the first and most influential was Roger Corman's 1967 The Trip, which made a good profit in the USA starred Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper and was scripted by Jack Nicholson - the trio responsible for Easy Rider two years later. The 1967 film's LSD hallucinatory sequences were more convincing than those depicted in Easy Rider.

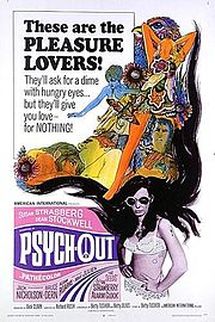

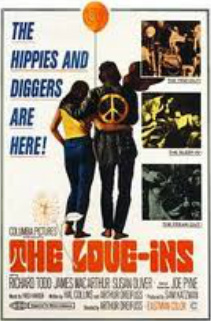

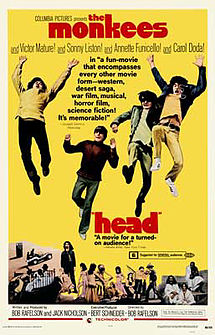

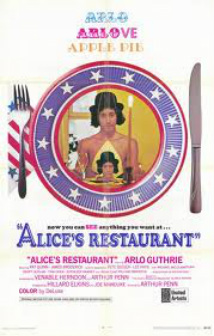

Whereas Easy Rider had considerable merit as a movie, unfortunately most of the Hollywood counterculture movies produced in its wake were clumsy, boring and ineptly written and directed. Although films like Psych-out are dross, they have considerable value today for the insight they throw on contemporary American responses to features of the counterculture. Easily the best of them is a film released within months of Easy Rider in 1969 and a few months before Zabriskie Point - Arthur Penn's Alice's Restaurant.

The making of Zabriskie Point

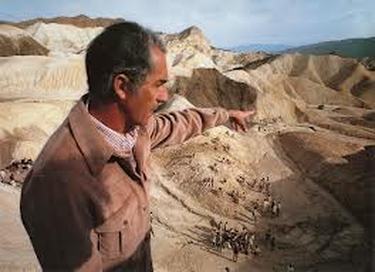

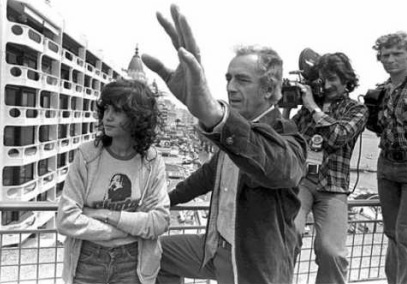

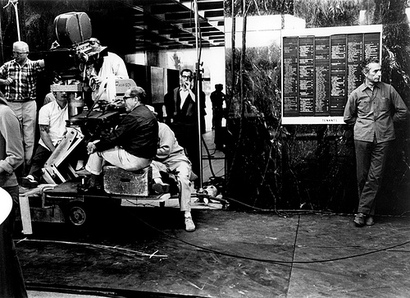

Antonionni filming in the lobby of the Los Angeles' Beneficial Plaza.

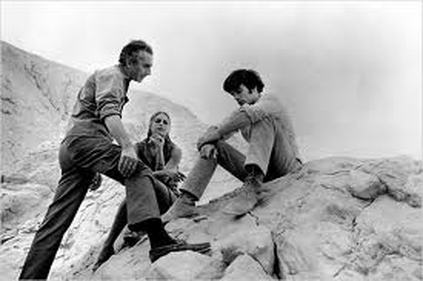

During his visit to the US during 1967-8, Antonioni observed the tumultuous social and cultural mood of the time, including the demonstrations and violence of the Chicago Democratic Party convention. He decided to make a film about a couple of disaffected countercultural youths, and selected two of them, neither with any acting experience, or, as the film was to expose, any acting talent. Daria Halprin was a Haight-Ashbury hippie; Mark Frechette a carpenter who lived in a Boston commune. Admirers of Antonioni and those on the European and American left eagerly anticipated a daring and vigorous endorsement of the mindset and milieu of the youthful American counterculture movement. MGM seems to have expected nubile hippies, currently fashionable anti-establishment attitudes, psychedelia and flower power galore, all of which would presumably attract hordes of young movie-goers..

The movie's "plot" - never an important element in an Antonioni film - was based on a brief newspaper article about a young man who stole a small airplane in Arizona and was killed by police while returning it. The perfunctory screenplay was the work of Antonionni, his then partner Clare Peploe, a left-wing journalist Frank Gardner, a promising young playwright, Sam Shepard, and the accomplished author Tonino Guerra, who had written scripts for most of Antonionni's acclaimed movies.

To the horror of the rapidly rotating roster of MGM producers and studio bosses, Antonioni went months over schedule, constantly reshooting scenes, introducing new ones, rewriting dialogue and changing his mind over locations, spending months selecting and rejecting music for the soundtrack. Antonioni's insistence on using his own Italian technical crew while their U.S. counterparts stood by on full pay was another source of contention. As a result Antonioni's budget spiralled out to $7 million - more than $5 million that it had cost to make Blow-up. MGM executives found the movie incomprehensible, the acting appalling. He also infuriated them with bitter criticisms of America in general and Hollywood in particular.

The movie's "plot" - never an important element in an Antonioni film - was based on a brief newspaper article about a young man who stole a small airplane in Arizona and was killed by police while returning it. The perfunctory screenplay was the work of Antonionni, his then partner Clare Peploe, a left-wing journalist Frank Gardner, a promising young playwright, Sam Shepard, and the accomplished author Tonino Guerra, who had written scripts for most of Antonionni's acclaimed movies.

To the horror of the rapidly rotating roster of MGM producers and studio bosses, Antonioni went months over schedule, constantly reshooting scenes, introducing new ones, rewriting dialogue and changing his mind over locations, spending months selecting and rejecting music for the soundtrack. Antonioni's insistence on using his own Italian technical crew while their U.S. counterparts stood by on full pay was another source of contention. As a result Antonioni's budget spiralled out to $7 million - more than $5 million that it had cost to make Blow-up. MGM executives found the movie incomprehensible, the acting appalling. He also infuriated them with bitter criticisms of America in general and Hollywood in particular.

Below: Antonionni at work on Zabriskie Point

The hostile reaction

Zabriskie Point opened in 1970 to critical derision and box-office disaster. It was condemned as Antonionni's worst movie and appeared on most lists of the worst films of 1970. Only the photography and the eclectic musical soundtrack escaped condemnation. Critics agreed that the movie was inert, the screenplay a mess, the acting woeful. All of Antonioni's flaws as a director - his tendency to mistake wilfull obscurity for profundity, his use of actors as mere ciphers, self-indulgent overdoses of ennui and alienation - were all too obviously and too lengthily on display in Zabriskie Point. Its most obvious flaws - acting, script, pretension -cruelly illustrated the director's trick of deliberately making his films obscure in order to attract critical attention. He explained to actor Peter Bowles (Blow-up) who complained to Antonioni that the director had removed a crucial speech, one that Bowles thought elucidated the film's meaning.

So I launched into an explanation of why he shouldn't cut the speech. He listened, and listened,

until finally I ran out of words. There was silence. So I said, "Erm, sir, are you going to put the speech

back in now?" He replied, "No. Because, Peter, you have explained to me exactly why I should cut it.

If I leave the speech in, everyone will know what the film is about, but if I take the speech out, everyone

will say it is about this, it is about that, it is about the other. It will be controversial."

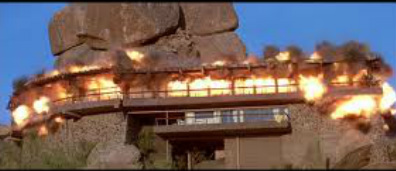

The movie exhibited the worst features of what Andrew Sarris called "Antoniennui", a morbidly self-conscious brand of intellectual malaise. Two of the movie's key sequences, the orgy in the desert and the apocalyptic slow-motion explosion of a luxury home and its contents - were met with mockery and contempt.

Those who had hoped for a movie that would be a revolutionary manifesto, revealing profound insights about 1960s era American angst while extolling countercultural values and condemning American capitalism were especially disappointed. Antonioni's implicit criticisms of America are trite and hackneyed: billboards, advertising, LA smog, LA traffic jams, real estate deals, faceless corporations, visual urban ugliness, conspicuous consumption, etc. But there was no grand overarching condemnation nor were there any suggestions of an irresistible revolutionary movement that would bring about enlightenment.

In fact, to the horror of the director's politically radical and countercultural admirers, Zabriskie Point presented members of the counterculture as narcissistic, self-indulgent, directionless and ineffectual, who couldn't make a sandwich let alone a revolution. His two protagonists ( just known as Mark and Daria) are bemused and, in the case of Mark, vacuous and arrogant. Daria seems good-natured but hardly dynamic. Mark's 'revolutionary' activity consists of (possibly) killing a policeman and threatening another with a gun and stealing a plane; Daria's contribution is to imagine blowing up a luxury home in the desert. Significantly, neither actually achieve anything by their actions / imaginations. These people are not the kind who will either bring about a revolution that will overthrow the 'Establishment' or achieve a new dawn of enlightenment. This was probably Antonioni's point but it was one that proved unacceptable for most of the director's admirers amongst American and European public intellectuals and those in the counterculture.

The crucial exchange in an argument between Daria and Mark presents a clear-cut division over attitudes. Daria says "There are a thousand different sides to every question", to which Mark replies that "You gotta have heroes and villains so that you can fix things up." This exchange of course is pure Antonioni: the failure to communicate, people talking past each other. Unfortunately, this theme is conveyed by way of pretentious, self-conscious and tedious dialogue desperately trying to appear hip:

Mark:Would you like to go with me?

Daria: Where?

Mark: Wherever I'm going.

Daria Are you *really* asking?

Mark: Is that your *real* answer?

As critics on both left and right pointed out, Antonionni seemed to have little grasp of what was actually happening in America at the time. Flower power, hippies and revolutionary activism had lost their radical chic and were losing the attention of the media. They were no longer "hip." The Vietnam war and its economic, political and cultural consequences was now the central issue, not the elitist and self-absorbed activities of a small and overwhelmingly privileged group of activists most of whom, unlike their working-class and less-education contemporaries, were safe from being called up to fight and die in a needless war.

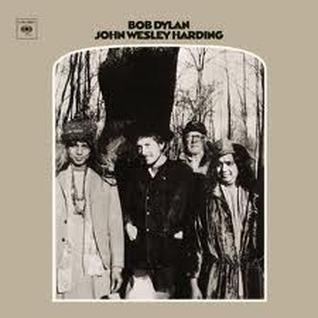

In terms of popular culture, this shift in attitude was best illustrated by the most recent albums of Bob Dylan. John Wesley Harding (1967) and Nashville Skyline (1969), both of which abandoned electric guitar and returned to folk and country music modes, lyrics and instrumentation. The absence of reference to the Vietnam conflict and the changing cultural and economic background, helps make Zabriskie Point strangely out of touch and irrelevant. Moreover, American audiences hadhad their fill of anti-establishment movies. Antonioni had made his film a couple of years too late and he had focused it on increasingly irrelevant groups and attitudes.

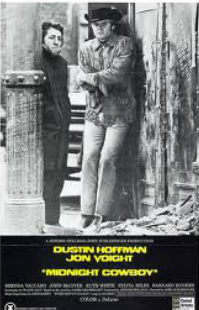

Unfortunately for Antonioni, his cinematic take on America in general and the counterculture in particular was made even more out of date, stereotyped and derivative by two films that had just preceded Zabriskie Point. Another foreigner, the British director John Schlesinger, had delivered a scathing but humane indictment of American society in Midnight Cowboy, which examined life on the fringes of a consumer culture. Midnight Cowboy was everything that Zabriskie Park was not - attuned to the problems of American life in the late sixties, superbly acted, uncondescending to its characters, and omitting big statements and flashy set-pieces in favour of a detailed examination of a neglected but significant section of U.S. society, those hoping to somehow move up from deprivation to participation in a materialistic society. By comparison, Zabriskie Point was trite and superficial.

So I launched into an explanation of why he shouldn't cut the speech. He listened, and listened,

until finally I ran out of words. There was silence. So I said, "Erm, sir, are you going to put the speech

back in now?" He replied, "No. Because, Peter, you have explained to me exactly why I should cut it.

If I leave the speech in, everyone will know what the film is about, but if I take the speech out, everyone

will say it is about this, it is about that, it is about the other. It will be controversial."

The movie exhibited the worst features of what Andrew Sarris called "Antoniennui", a morbidly self-conscious brand of intellectual malaise. Two of the movie's key sequences, the orgy in the desert and the apocalyptic slow-motion explosion of a luxury home and its contents - were met with mockery and contempt.

Those who had hoped for a movie that would be a revolutionary manifesto, revealing profound insights about 1960s era American angst while extolling countercultural values and condemning American capitalism were especially disappointed. Antonioni's implicit criticisms of America are trite and hackneyed: billboards, advertising, LA smog, LA traffic jams, real estate deals, faceless corporations, visual urban ugliness, conspicuous consumption, etc. But there was no grand overarching condemnation nor were there any suggestions of an irresistible revolutionary movement that would bring about enlightenment.

In fact, to the horror of the director's politically radical and countercultural admirers, Zabriskie Point presented members of the counterculture as narcissistic, self-indulgent, directionless and ineffectual, who couldn't make a sandwich let alone a revolution. His two protagonists ( just known as Mark and Daria) are bemused and, in the case of Mark, vacuous and arrogant. Daria seems good-natured but hardly dynamic. Mark's 'revolutionary' activity consists of (possibly) killing a policeman and threatening another with a gun and stealing a plane; Daria's contribution is to imagine blowing up a luxury home in the desert. Significantly, neither actually achieve anything by their actions / imaginations. These people are not the kind who will either bring about a revolution that will overthrow the 'Establishment' or achieve a new dawn of enlightenment. This was probably Antonioni's point but it was one that proved unacceptable for most of the director's admirers amongst American and European public intellectuals and those in the counterculture.

The crucial exchange in an argument between Daria and Mark presents a clear-cut division over attitudes. Daria says "There are a thousand different sides to every question", to which Mark replies that "You gotta have heroes and villains so that you can fix things up." This exchange of course is pure Antonioni: the failure to communicate, people talking past each other. Unfortunately, this theme is conveyed by way of pretentious, self-conscious and tedious dialogue desperately trying to appear hip:

Mark:Would you like to go with me?

Daria: Where?

Mark: Wherever I'm going.

Daria Are you *really* asking?

Mark: Is that your *real* answer?

As critics on both left and right pointed out, Antonionni seemed to have little grasp of what was actually happening in America at the time. Flower power, hippies and revolutionary activism had lost their radical chic and were losing the attention of the media. They were no longer "hip." The Vietnam war and its economic, political and cultural consequences was now the central issue, not the elitist and self-absorbed activities of a small and overwhelmingly privileged group of activists most of whom, unlike their working-class and less-education contemporaries, were safe from being called up to fight and die in a needless war.

In terms of popular culture, this shift in attitude was best illustrated by the most recent albums of Bob Dylan. John Wesley Harding (1967) and Nashville Skyline (1969), both of which abandoned electric guitar and returned to folk and country music modes, lyrics and instrumentation. The absence of reference to the Vietnam conflict and the changing cultural and economic background, helps make Zabriskie Point strangely out of touch and irrelevant. Moreover, American audiences hadhad their fill of anti-establishment movies. Antonioni had made his film a couple of years too late and he had focused it on increasingly irrelevant groups and attitudes.

Unfortunately for Antonioni, his cinematic take on America in general and the counterculture in particular was made even more out of date, stereotyped and derivative by two films that had just preceded Zabriskie Point. Another foreigner, the British director John Schlesinger, had delivered a scathing but humane indictment of American society in Midnight Cowboy, which examined life on the fringes of a consumer culture. Midnight Cowboy was everything that Zabriskie Park was not - attuned to the problems of American life in the late sixties, superbly acted, uncondescending to its characters, and omitting big statements and flashy set-pieces in favour of a detailed examination of a neglected but significant section of U.S. society, those hoping to somehow move up from deprivation to participation in a materialistic society. By comparison, Zabriskie Point was trite and superficial.

Zabriskie Point awkwardly combines a disatrous attempt to appear, in the argot of the day, 'hip', 'cool' and 'with it', with a rather more interesting if ultimately unsuccessful recycling of Antonioni's traditional concerns. Thus we have trite portrayals of the sterility of corporate America, the envisaged destruction of an edifice embodying materialism and consumerism, with images of the isolation of the individual intruding on the natural world, plus an unintentionally hilarious depiction of mass couplings in a barren landscape.

Another film released just before Zabriskie Point was Arthur Penn's Alice's Restaurant, based on Arlo Guthrie's long talking blues song about the draft. This was Penn's first movie after the success of Bonnie and Clyde. Humorous and satrical in parts, the film has a wistful and elegiac mood. Unlike Antonioni, Penn does not make the mistake of regarding the counterculture as the preserve of the young and the politically radical. And unlike Antionini, Penn understands the overwhelming importance of the draft and the Vietnam war as the catalyst for protest. His characters are authentic and essentially decent, even the police, unlike the superficial stereotypes that populate Zabriskie Point.

Simple, basic, unpretentious, proclaiming a return to the roots of American music. The covers of Dylan's 1967 and 1969 albums, and their music, constitute a rejection of psychedelia and flower-power influences.

Arthur Penn's subtle and gently elegiac Alice's Restaurant (below left) is essential viewing for anyone wanting to gain insight into both the American counterculture at the end of the 1960s and, more generally, into the American mood at the end of that momentous era. Midnight Cowboy (below right) is a gritty, disturbing look at the underside of the the American dream. Its critique of U.S. culture, unlike Antonioni's is both subtle and convincing.

Arthur Penn's subtle and gently elegiac Alice's Restaurant (below left) is essential viewing for anyone wanting to gain insight into both the American counterculture at the end of the 1960s and, more generally, into the American mood at the end of that momentous era. Midnight Cowboy (below right) is a gritty, disturbing look at the underside of the the American dream. Its critique of U.S. culture, unlike Antonioni's is both subtle and convincing.

Zabriskie Point as a continuation of Antonioni's thematic concerns

A major reason for the critical response to Zabriskie Point was that Antonioni did not make the type of movie that he had been expected to make. He decribed the USA as "the most interesting country in the world" because it was there that "some of the essentual truths and contradictions of our time can be isolated in their pure state." But although he mixed in American radical chic circles and echoed some of their currently fashionable tropes about the counterculture, youth and revolutionary politics, he was ultimately more interested in his customary intellectual and thematic concerns. Above all, these focused on the plight of people unable to articulate exactly what they wanted, who were searching for some direction in their lives but distracted and made indecisive by the temptations of materialism and consumerism. Antonioni was also fascinated by the contrasts between the beauty and solitude of the natural world and its contrast with the crowded, polluted, confining modern world of commerce and industry. This aspect of his critique of modern life was made most obviously in Red Desert and it is reasserted vigorously in Zabriskie Point.

Indeed, the director's main concerns in Zabriskie Point are not really about youth, counterculture and revolutionary politics, which are only perfunctorily and clumsily acknowledged. Once the scene shifts from Los Angeles to the desert, the movie finally lurches into intermittent life. It is in Death Valley and its desolate surrounds - "so primitive, like the moon" - that the real core of Antonioni's interest can be found. Antonioni is not really interested in Mark and Daria's counterculture ideas and revolutionary mentality. Instead, he returns to his habitual themes. The pair's increasingly tiresome attempts to communicate with each other and their inability to articulate their ideas (foreshadowed in the opening sequence of would-be revolutionaries ineffectually arguing about tactics) are what really interest him. He is equally interested in using Death Valley and the desert to exemplify another of his habitual themes: how landscape/environment/ settings can reveal characters' moods and states of mind, aridity as a reflection of modern life. And the movie's finale with the desert home and contents exploding (in Daria's mind) exemplifies Antonioni's distaste for materialism and consumerism.

Indeed, the director's main concerns in Zabriskie Point are not really about youth, counterculture and revolutionary politics, which are only perfunctorily and clumsily acknowledged. Once the scene shifts from Los Angeles to the desert, the movie finally lurches into intermittent life. It is in Death Valley and its desolate surrounds - "so primitive, like the moon" - that the real core of Antonioni's interest can be found. Antonioni is not really interested in Mark and Daria's counterculture ideas and revolutionary mentality. Instead, he returns to his habitual themes. The pair's increasingly tiresome attempts to communicate with each other and their inability to articulate their ideas (foreshadowed in the opening sequence of would-be revolutionaries ineffectually arguing about tactics) are what really interest him. He is equally interested in using Death Valley and the desert to exemplify another of his habitual themes: how landscape/environment/ settings can reveal characters' moods and states of mind, aridity as a reflection of modern life. And the movie's finale with the desert home and contents exploding (in Daria's mind) exemplifies Antonioni's distaste for materialism and consumerism.

|

|

|

Above left: the (in)famous climax to the movie: the exploding house and contents slow-motion sequence.

Above right: the excellent trailer for the film provides an accurate summary of the movie from start to finish in under two minutes. Enjoy!

Above right: the excellent trailer for the film provides an accurate summary of the movie from start to finish in under two minutes. Enjoy!