Lincoln: (2012): Director - Steven Spielberg

Spielberg's Take on Abraham Lincoln

What sort of film did Spielberg hope to make?

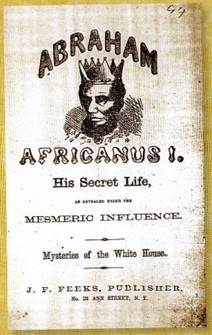

Abraham Lincoln has featured in countless movies, but comparatively few have devoted their full running-time to aspects of his life and career. Indeed, the last such film was made more seventy years ago. Only three of these movies have lasting merit, and, unsurprisingly, two of the them were directed by great American directors. D.W. Griffith made Abraham Lincoln in 1931 and Henry Ford made the superb Young Mr. Lincoln in 1939. The next year the competent John Cromwell directed Abe Lincoln in Illinois, a film significant mainly for Raymond Massey's portrayal of Lincoln, a performance which he repeated in several other other period films for the next half-century and which became embedded in the minds of several generations in the USA and overseas as the epitome of Lincoln the man and President.

Spielberg was determined to approach Lincoln from a different standpoint. His inspiration for making the film came several years ago, after reading historian Doris Kearns Goodwin's book Team of Rivals: the Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. Spielberg and his scriptwriter, playwright Tony Kushner, decided not to make a film covering Lincoln's life and political career as Griffith did. Nor would his film cover a lengthy and significant aspect of Lincoln's life, as did both Young Mr. Lincoln and Abe Lincoln in Illinois. Instead, Spielberg and his scriptwriter Tony Kushner worked from more restricted perspective. They confined their focus to a few months (mainly January)in early 1865 and to a key political event: the President's struggle to persuade Congress to abolish slavery by passing the 13th Amendment to the Constitution before the civil war ended. "I wanted the audience to get into the working process of the President", Spielberg declared.

The result was what the movie critic A.O. Scott calls " a political thriller" and what the Bloomberg News describes as a "mash note to brass-knuckle American politics". Both Spielberg and Kushner have taken a brave box-office gamble. The crucial part of Spielberg's "working process" involved Lincoln overcoming myriad political, personal and regional and factional animosities amongst the politicians and somehow patching up a coalition of votes in favor of the amendment. Although this approach to the movie had the advantage of highlighting Lincoln's superb political skills and statesmanlike vision, its audience appeal would presumably be fairly limited.

Spielberg was determined to approach Lincoln from a different standpoint. His inspiration for making the film came several years ago, after reading historian Doris Kearns Goodwin's book Team of Rivals: the Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. Spielberg and his scriptwriter, playwright Tony Kushner, decided not to make a film covering Lincoln's life and political career as Griffith did. Nor would his film cover a lengthy and significant aspect of Lincoln's life, as did both Young Mr. Lincoln and Abe Lincoln in Illinois. Instead, Spielberg and his scriptwriter Tony Kushner worked from more restricted perspective. They confined their focus to a few months (mainly January)in early 1865 and to a key political event: the President's struggle to persuade Congress to abolish slavery by passing the 13th Amendment to the Constitution before the civil war ended. "I wanted the audience to get into the working process of the President", Spielberg declared.

The result was what the movie critic A.O. Scott calls " a political thriller" and what the Bloomberg News describes as a "mash note to brass-knuckle American politics". Both Spielberg and Kushner have taken a brave box-office gamble. The crucial part of Spielberg's "working process" involved Lincoln overcoming myriad political, personal and regional and factional animosities amongst the politicians and somehow patching up a coalition of votes in favor of the amendment. Although this approach to the movie had the advantage of highlighting Lincoln's superb political skills and statesmanlike vision, its audience appeal would presumably be fairly limited.

The essential background to the struggle over the 13th Amendment,early 1865

Lincoln (pictured in this scene with William Seward , his Secretary of State), was determined to abolish slavery before the civil ended. He realised that his Emancipation Proclamation of 1862, although symbolically important, was very limited in its scope and of fragile legality. The end of war would mean that the legal status of slavery in slave states would still remain intact. With the Confederacy's leaders realising that defeat was now inevitable and that the South would eventually be returned to the Union, there was a real danger that the southern states could rejoin with slavery still intact and the whole tragic conflict would be eventually resumed. A Constitutional amendment abolishing slavery would prevent this possibility. It would also provide a moral and humanitarian justification for Lincoln fighting the civil war.

|

During 1864 a bill proposing a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery was introduced by Missouri Senator John Henderson, a Lincoln ally, and supported by a former rival of Lincoln's, Senator Lyman Trumbull. The measure passed the Senate but was rejected by the House of Representatives. \After his re-election in November, Lincoln set about trying to construct coalition of of Representatives to pass the amendment. Many of those he had to persuade were 'lame-duck' representatives from the opposition Democratic Party, men who had lost their seats in the November election but still sat until the new Congress would meet months later. Lincoln had to overcome petty political rivalries, racism, abolitionist demands for stronger legislation, and a widespread demand that he finish the war before embarking on such a controversial move. Even members of his own Cabinet were unhappy.

|

|

Even William Seward, the Secretary of State and a man who Lincoln relied on to get the House to pass the amendment, had his doubts about abolition. During 1860-1 Seward had proposed appeasing the South by offering a bill that would prevent Congress passing any amendment to the Constitution that would have abolished slavery. In fact, just before the civil war broke out in 1861, the House of Representatives actually passed such legislation. Known as the Corwin amendment after its Republican proposer, Representative Thomas Corwin of Ohio, it stated

"No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State (References: Ohio Historical Society; Ohio State Capitol Museum). Ironically, President Lincoln sent the amendment to the states for them to vote on its ratification. Only two did,so it failed to be adopted but even today it remains that historical curiosity - an unratified constitutional amendment. |

Mary Todd LincolnSally Field played Lincoln's wife. Mary Lincoln was an emotionally fragile, psychologically-troubled woman, prone to depression and vindictive outbursts. Tactless, embittered and unstable, prone to spells of crippling depression verging on dementia, the fraught relationship between husband and wife was another burden Lincoln faced during his Presidency.

|

|

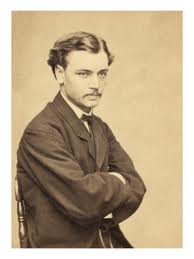

Robert's life was saved by the brother of Lincoln's assassin.

Jersey Station [August?] 1864 "The incident occurred while a group of passengers were late at night purchasing their sleeping car places from the conductor who stood on the station platform at the entrance of the car. The platform was about the height of the car floor, and there was of course a narrow space between the platform and the car body. There was some crowding, and I happened to be pressed by it against the car body while waiting my turn. In this situation the train began to move, and by the motion I was twisted off my feet, and had dropped somewhat, with feet downward, into the open space, and was personally helpless, when my coat collar was vigorously seized and I was quickly pulled up and out to a secure footing on the platform. Upon turning to thank my rescuer I saw it was Edwin Booth, whose face was of course well known to me, and I expressed my gratitude to him, and in doing so, called him by name." p. 70-71 of "Robert Todd Lincoln: A Man In His Own Right" by John S. Goff. |

Robert Todd LincolnThe Lincoln's oldest son, played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt, ignored his parent's strenuous objections and dropped out of study at Harvard to join the ranks of Union soldiers and fight in the waning months of the civil war.

Robert was a shy, thoughtful but determined person, rather overwhelmed by the spotlight that fell on the Presidential family. He eventually became a lawyer, served as Secretary of War for two Presidents, and later served as the equivalent of American ambassador to Britain. Amazingly, he was present at two presidential asassinations:those of Presdents James Garfield and William McKinley. (He did not go to the Ford Theater but was with Lincoln when the President died the next day.) And his life was once saved by the brother of Lincoln's assassin (see left) |

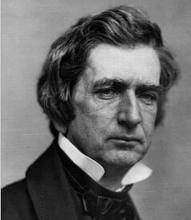

William SewardOne of the leading contendsers for the Republican nomination for the presidency in 1860, Seward (played by William Strathairn) became one of Lincoln's "team of rivals" in the President's Cabinet. As Secretary of State Seward was given a relatively free hand by Lincoln, and shrewdly handled the difficult task of keepimng Britain neutral in the civil war. As time went on Seward, unlike Lincoln, became less committed to emancipation of the slaves. Ge was seriously injured on his sickbed by one of the group who took part in the conspiracy to kill the president.

|

Thaddeus StevensStevens was a tireless campaigner against slavery and acted as Lincoln's chief enforcer in persuading the House of Representatives by both fair means and foul to pass the 13th Amendment. Sarcastic, vindictive, embittered and impatient, he shrewdly used his key post as Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee to push the legislation through the House. Tommy Lee Jones' performance does a fine job of capturing this fascinating politician's fiery personality and vicious speech.

|

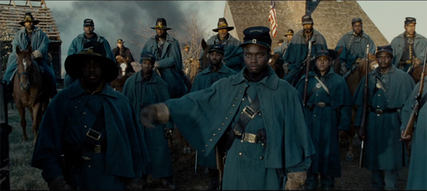

The Role of African-Americans in Spielberg's Lincoln

Does Lincoln represent its African-American characters as merely "passive"?

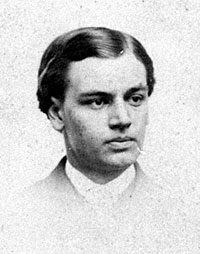

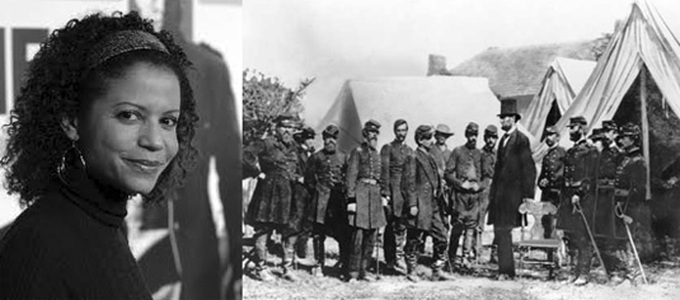

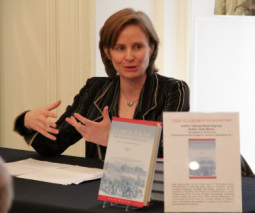

Kate Masur, historian at Northwestern.

Some historians have pointed out that the decision of Spielberg and Kushner to severely limit their movie's scope to a study of Lincoln's attempts to get the thirteenth amendment abolishing slavery through the House of Representatives overlooks the decades of efforts of both white abolitionists and African-Americans themselves to prepare the way for the passage of such legislation. Kate Masur, an historian at Northwestern, whose specialty is research into the activism of the civil war era in Washington D.C, condemns "Lincoln" for what she claims is the movie's representation of African-Americans. For Masur, the film's "African-American characters do almost nothing but passively wait for white men to liberate them....Lincoln gives us only faithful servants waiting passively for the day of Jubilee.... [it] helps perpetuate the notion that African-Americans have offered little of substance to their own liberation."

According to Masur, emancipation is portrayed as "a gift from white people to black people". She insists that blacks shown in the movie are stereotypes, lack agency, and have been given few notable lines. They are there to represent gratitude and stoicism, but are not credited with playing a significant part in the process of emancipation. For example, the movie includes Elizabeth Keckley, a black woman who was an important organizer of black women in the city. Although Masur strangely describes her as a "servant" she was in fact, and is shown in the movie as, a confidante of Mary Lincoln as well as a self-sufficient entrepreneur: dressmaker to the President's wife. As portrayed by actor Gloria Reuben (herself a forceful and articulate figure in African-American affairs), Keckley is intelligent, judicious, authoritative. Indeed, Mrs Lincoln seems to be emotionally dependent on Keckley, not the other way round.

Her criticisms are based on a fundamental premise - the didn't make the movie according to my taste and my interests. Masur's area of expertise concerns the roles that African-Americans played in Civil War era Washington, especially their roles in campaigning for abolition and in raising the consciousness of fellow blacks about racial,social and economic injustice. She is annoyed that these undoubtedly significant features of the era are not included in the movie. Thus she complains that Lincoln does not show Keckley discussing the relief work that both she and Mrs Lincoln engaged in.

Mansur chooses to ignore that Spielberg made it clear in his comments and in the movie itself that its s focus was deliberately limited. This is not a picture with a wide social perspective; it is an examination of two features: the tortuous political process of getting a reluctant House of Representatives to pass the 13th amendment, and what this process reveals about Lincoln the man and the President. And that process was to be determined by political institutions and conventions from which at that time African-Americans were excluded and by groups of politicians who were overwhelmingly white.

Had Spielberg wanted to make a film about African-Americans' role in their emancipation process he would doubtless have used as his source Masur's book An Example for All the Land, which examines black political and social activism in Washington D.C. in the 1860s. But Spielberg intended to make a completely different type of film, which is why he sourced Doris Kearns Goodwin's Band of Rivals. So he focused on the complex yet fascinating political struggle and omitted other issues.

Kate Masur snidely comments that "As in Schindler's List and Saving Private Ryan, 'his purpose is more to entertain and inspire than to educate." She might like to consider that entertainment and inspiration should be the objectives of a wide educator.

Her criticisms are based on a fundamental premise - the didn't make the movie according to my taste and my interests. Masur's area of expertise concerns the roles that African-Americans played in Civil War era Washington, especially their roles in campaigning for abolition and in raising the consciousness of fellow blacks about racial,social and economic injustice. She is annoyed that these undoubtedly significant features of the era are not included in the movie. Thus she complains that Lincoln does not show Keckley discussing the relief work that both she and Mrs Lincoln engaged in.

Mansur chooses to ignore that Spielberg made it clear in his comments and in the movie itself that its s focus was deliberately limited. This is not a picture with a wide social perspective; it is an examination of two features: the tortuous political process of getting a reluctant House of Representatives to pass the 13th amendment, and what this process reveals about Lincoln the man and the President. And that process was to be determined by political institutions and conventions from which at that time African-Americans were excluded and by groups of politicians who were overwhelmingly white.

Had Spielberg wanted to make a film about African-Americans' role in their emancipation process he would doubtless have used as his source Masur's book An Example for All the Land, which examines black political and social activism in Washington D.C. in the 1860s. But Spielberg intended to make a completely different type of film, which is why he sourced Doris Kearns Goodwin's Band of Rivals. So he focused on the complex yet fascinating political struggle and omitted other issues.

Kate Masur snidely comments that "As in Schindler's List and Saving Private Ryan, 'his purpose is more to entertain and inspire than to educate." She might like to consider that entertainment and inspiration should be the objectives of a wide educator.

|

|

|