The Campaign Against Hollywood Movies Pt.2

Both these movies were very popular in interwar New Zealand. The Jazz Singer was one of first talkie musicals shown here, but sometimes regarded askance for ; Henry Viii was praised for its essential "Britishness" of subject matter, production values and country of origin. From the twenties through to the forties many cultural commentators insisted on the superiority of British movies to their Hollywood counterparts. But the New Zealand picture-going public knew better: American movies was far more popular than the usually lacklustre and torpid products of the moribund British film industry of the time.

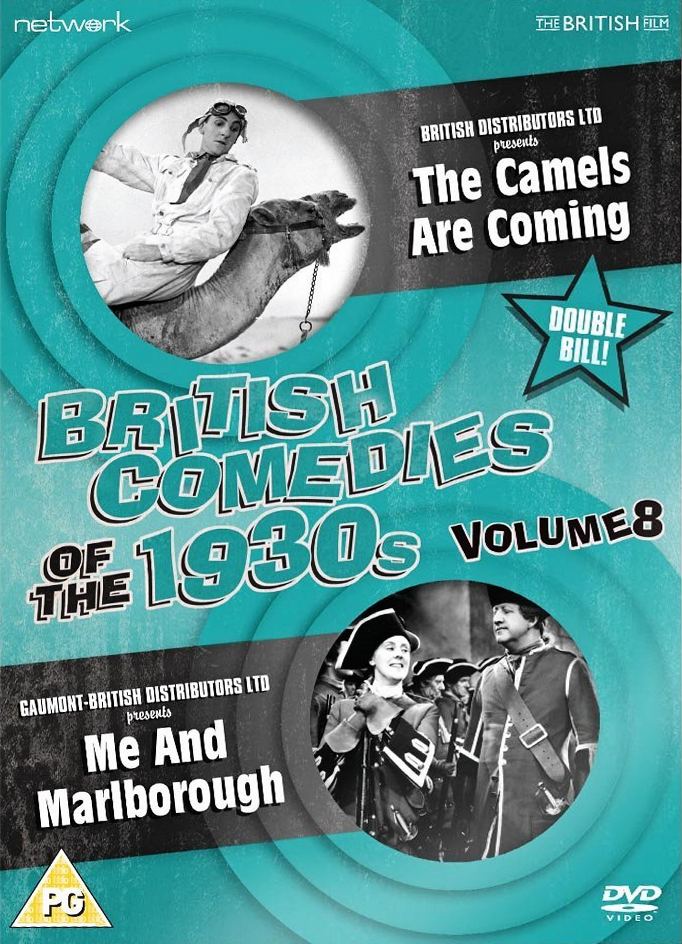

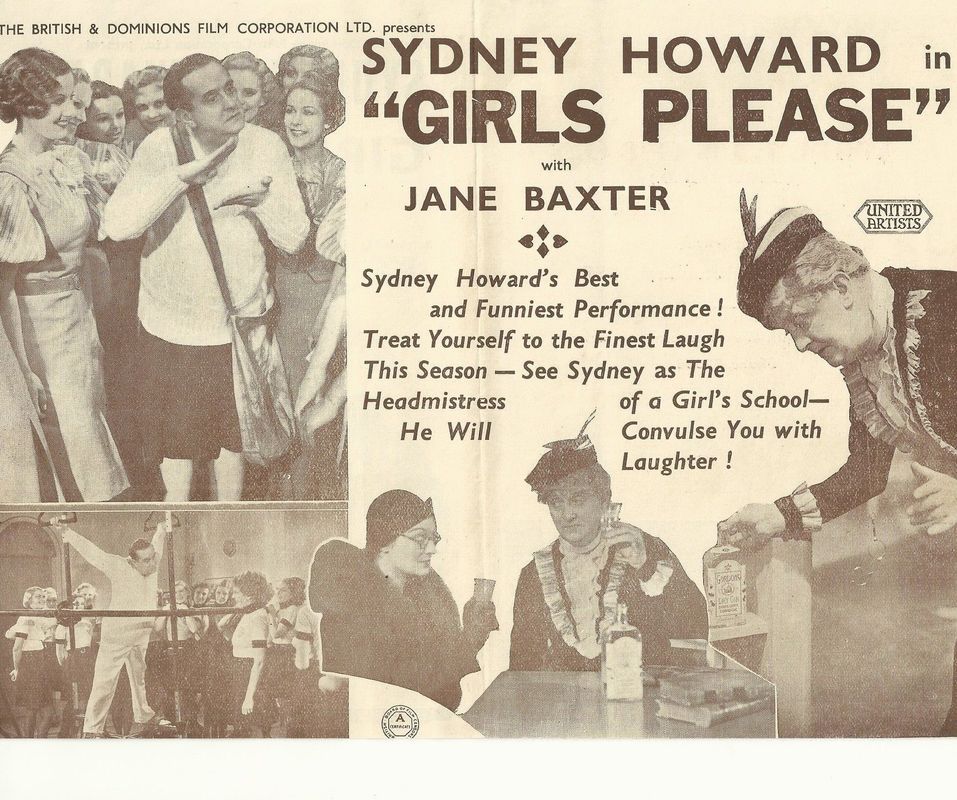

The 1920s and 1930s: American movies & the "British is best' mentality

2. With very few exceptions (HItchock's English movies, Private Life of Henry VIII),British movies in the interwar years were usually inferior to their Hollywood counterparts. In almost every movie-making aspect - cinematography, script, production values, direction, acting - British movies were second-rate. With a few exceptions, like Hitchcock, British films in the 1920s and 1930s were essentially filmed stage plays that made little attempt to hide their origins. Most British films of that era were "quota quickies" - made as cheaply and quickly as possible to fill the quota of British films stipulated by the Cinematograph Films Act of 1927. However, some comedies were successful,notably those with Will Hays and George Formby.

But in New Zealand cultural and moral guardians continued to disparage Hollywood movies while simultaneously praising the 'virtues' of British cinema. To the intense annoyance of these elites, New Zealand moviegoers voted with their feet (and wallets) for Hollywood over Pinewood.

Why did New Zealand's elites condemn Hollywood movies and endorse British cinema in

inter-war New Zealand?

1. Hollywood movies were accused of being "tasteless', crass and sentimental. Thus In 1929 a parliamentarian, H. Thomson, condemned U.S. films as full of ‘sickly sentiment and a good deal of vulgarity....’ New Zealanders were in danger of being corupted by American ideas and values.54 According to Thomson, ‘the low type of American picture generally shown at the Saturday-afternoon matinees not only must have an effect upon the speech, but it has a more positive danger in the ideas that are suggested. I need not refer so much to sexual and problem pictures, which are frequently shown, but to those that show a perverted idea of justice and a glorification of the criminal and the bandit.’

2. Hollywood films supposedly spread American slang and pronunciation to the detriment of 'proper' English pronunciation and proper English values. ‘The American dialect and the barbarous “Yankee” intonation always grate on one’ complained a Christchurch viewer of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. ‘Whoever is responsible should see should see that the interests of good English and good taste such rubbish is not inflicted on the people of New Zealand’.57 Two years later Thomson reiterated these concerns about the elocutionary and cultural standards of New Zealanders by urging the government to direct the film censor ‘to purge, as far as possible, the vile American accents of many of the “talkie” films and the sickly sentimental psuedo-morality which seeks its inspiration among the lowest social strata of the population’.58 He insisted that the New Zealand audiences of Hollywood movies lacked the cultural taste and judgement of their social and educational superiors. He disparaged the audience who viewed the session of Broadway Melody he attended in 1929: ‘it is deplorable that the taste of the people should be so reduced as to find its mental pabulum in.... [such films]’’59 Such patronising attitudes were occasionally refuted. In 1934 Hamilton’s Cinema News defended

'the people who go to shows to enjoy themselves in their own way and not to cause themselves perpetual headaches in looking for points to criticize. The superior ones of the earth have ever been above the things that entertain the ordinary majority.'60

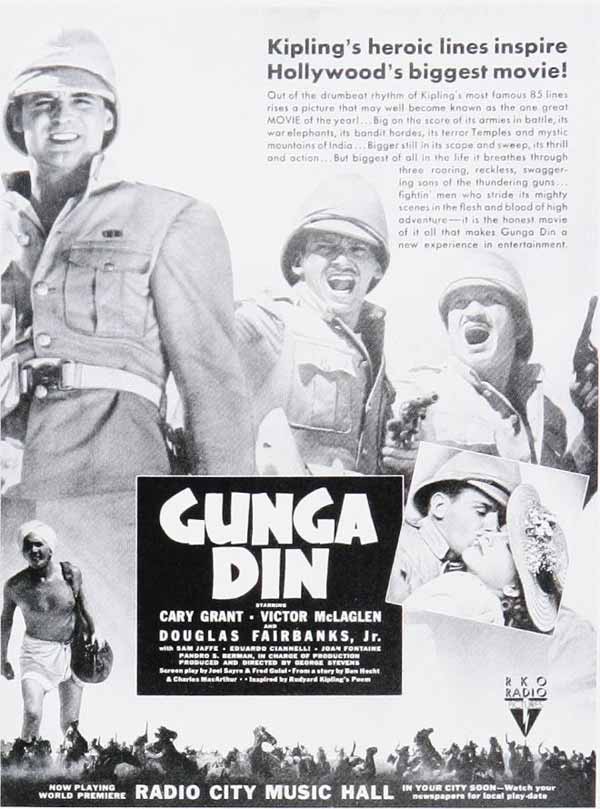

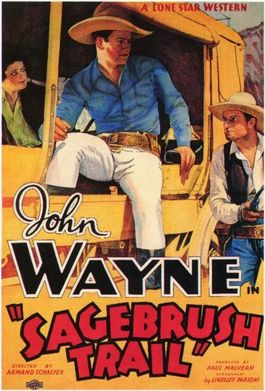

Below: to the horror of New Zealand's moral and cultural guardians of the interwar years, the nation's audiences loved the movie stars and film genres that Hollywood's movie industry produced. The Marx Brothers, Charlie Chaplin, Shirley Temple, Cary Grant and western and action films were especially popular.

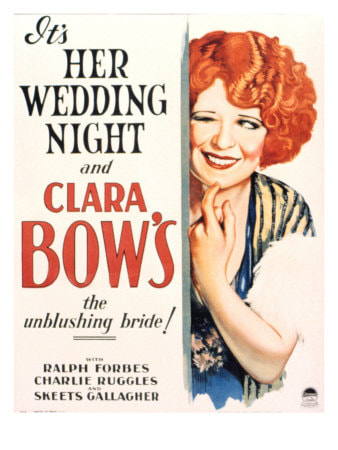

The movies and stars of the thirties and early firties that were so popular in the U.S.A. also met with a happy reception in New Zealand. Most members of the cultural elites looked askance at Hollywood genres such as musicals, madcap comedies and rousing adventure films, regarding them as superficial and mindkess. But within decades these genres and their movies , as well as their box-office stars like Shirley Temple, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Clara Bow and Cary Grant, became recognised as cultural icons By comparison most British movies of that era have been forgotten. The movies of Alfred Hitchcock (e.g. The 39 Steps, The Lady Vanishes) are the most obvious exception.

3. The overwhelming civic and intellectual consensus of the interwar era denigrated the taste and values of New Zealand's cinema-going audiences. Their preference for Hollywood films was sometimes cited as evidence of their poor judgement. Several editorials in the Otago Daily Times in the 1930s insisted that movies were of dubious artistic quality precisely because they aimed to appeal to the general New Zealand public, which the Times perceived as having lower standards of taste and aesthetic judgement than their social and cultural superiors.

'Its circle of admirers is much wider than that embracing lovers of good music, readers of fine books, or patrons of the other fine arts.... The backbone of the public support ...[for] the film industry is provided by the millions who may never care for any other music than jazz and songs of sentiment, and who may depend for their reading upon the daily newspaper and regard art as only those coloured prints that depict homely scenes at the fireside or the shaggy Highland cattle standing bleakly amidst extraordinarily purple heather. '

Such an audience, passive and intellectually undemanding, was highly susceptible to detrimental influences from films. Unfortunately for them, and unlike the minority of ‘discerning picture-goers’, the impact of cinema was likely to be damaging, for films frequently dealt with ‘disagreeable’ subjects ...the more sordid aspects of life’. Consequently, New Zealand cinemagoers, young and old, required protection from these unsavoury features.61

According to the Times, movies were an inferior aesthetic experience compared with stage drama. In cinema, especially American cinema, ‘the mind was diverted from thinking to seeing, from a study to a spectacle....’ The ‘higher type of mind’ sought drama as a source for intellectual reflection. But the ‘common type’ required emotional satisfaction, mere passive entertainment of the senses, ‘untutored by introspective analysis’. From this perspective, there was a division between cinema and its more refined and culturally correct counterpart, stage drama. There was also a split between their respective audiences, the one large but unthinking, and the other, smaller but refined and thoughtful. Talkies, in the Times’ perception, possessed an immediate, visceral but superficial appeal to the senses, not the intellect. American films were especially guilty of this cultural crime, for they were initially aimed at the vast, psychologically callow congeries of humanity gathered in the great cities of the New World, the more especially as the perilous and picturesque experiences with natives have been succeeded by the viler perils and animalism of gangsters.'

What especially concerned the Times was the imminent threat to New Zealand youth presented by the ‘ethical standards of the lower grades of the New World’ insinuating themselves here by way of Hollywood movies. Thus vigilance was needed to ensure ‘the foul sewers of man’s lower nature are not paraded on the public screen’.

4. Racism also played a role in perceptions of American cinema during these formative interwar years. In 1936 the Attorney-General agonized over the alleged influence of Hollywood on the street culture of some young Maori. 'They

dress and act the part of ...[film] characters ...usually the characters of the wild west films. That the films do have a strong suggestive influence is thus clear and that this influence is in the direction of increasing crime is also clear.

The Film Censor’s files of that era contain letters complaining about the presence of negro music and negro actors in American musical films, which were especially popular in New Zealand with the arrival of ‘talkies’. W.W. Tanner, the censor in the 1930s, agreed with these complaints . In January 1931 he described how he dealt with such films: ‘he had blocked all of them’. According to Tanner, ‘the general public did not know what they had been protected from’, namely cabaret and other scenes set in ‘surroundings of low quality’. Other public officials also condemned Hollywood musicals as indecent. T.B. Strong, New Zealand's Director of Education in the late 1920s, blamed ‘Yankee cinematograph pictures’ for their ‘insidious influence on our young folk’. He told Wellington Girls’ College pupils and parents of his objection to cabaret sequences

which not only included an ‘unashamed exhibition of female nakedness’, but also contained slang ‘characteristic of the less-educated American.’

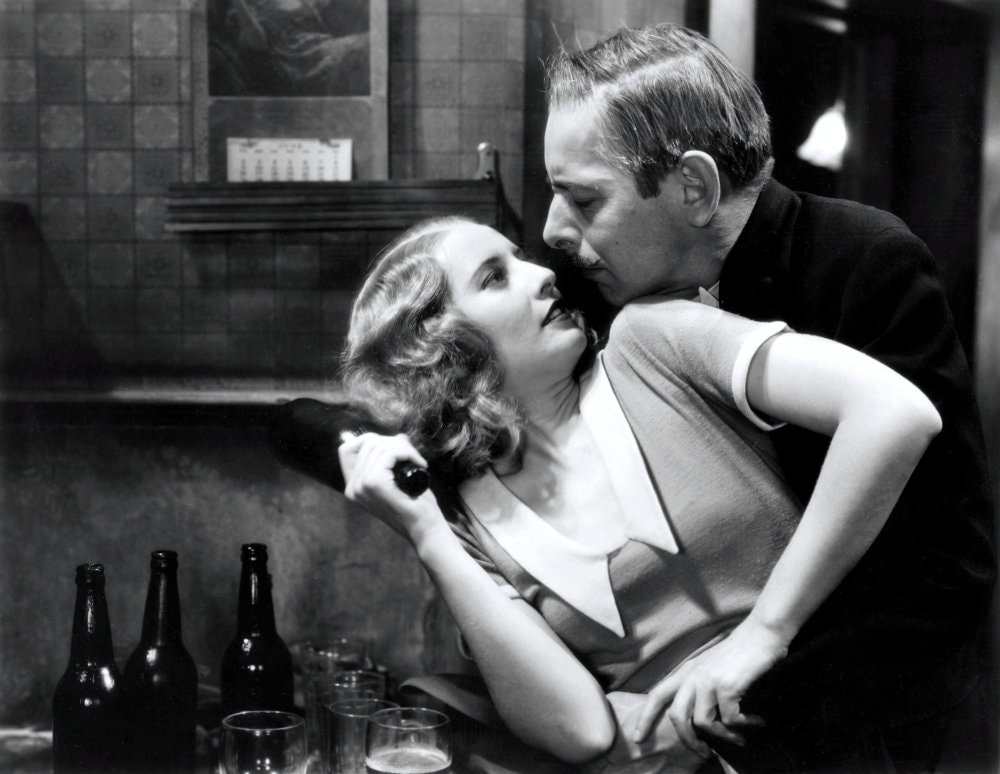

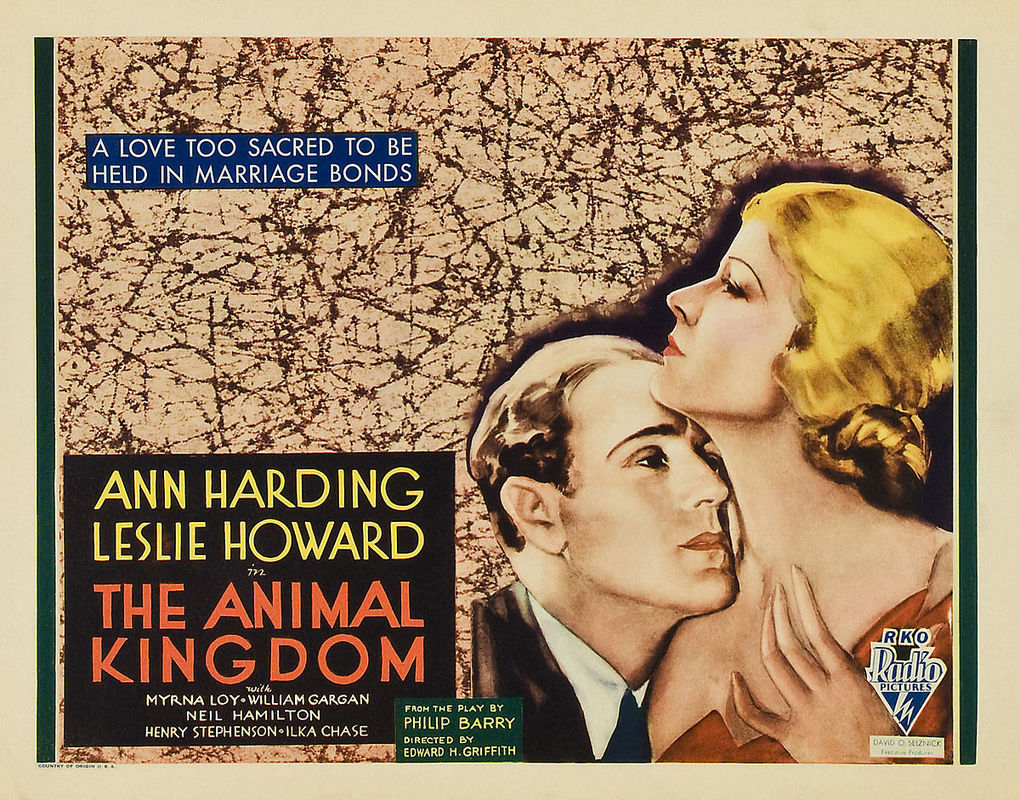

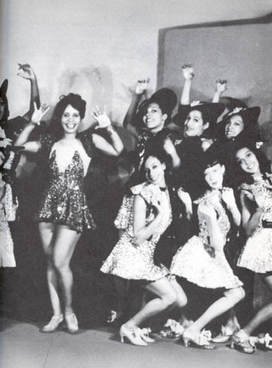

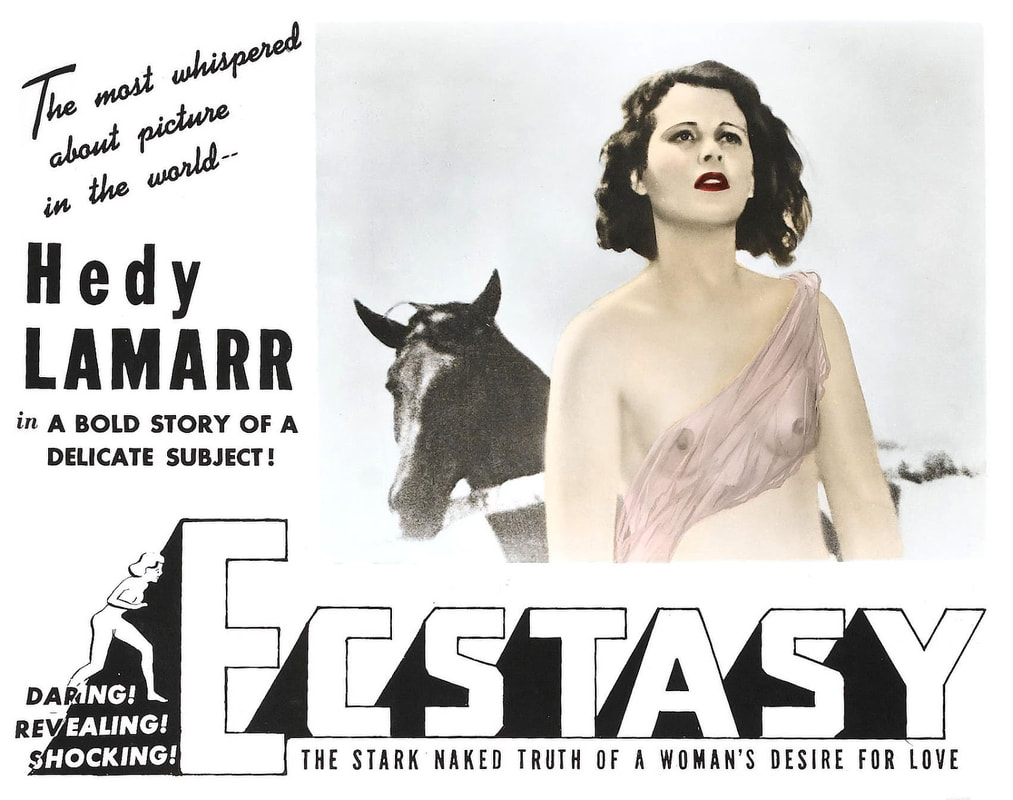

Below: Risque titles, risque costumes, temptresses, sexually chatged scenes, night-club and cabaret scenes -and, the horror! - black entertainers on-screen and alongside white actors.

'Its circle of admirers is much wider than that embracing lovers of good music, readers of fine books, or patrons of the other fine arts.... The backbone of the public support ...[for] the film industry is provided by the millions who may never care for any other music than jazz and songs of sentiment, and who may depend for their reading upon the daily newspaper and regard art as only those coloured prints that depict homely scenes at the fireside or the shaggy Highland cattle standing bleakly amidst extraordinarily purple heather. '

Such an audience, passive and intellectually undemanding, was highly susceptible to detrimental influences from films. Unfortunately for them, and unlike the minority of ‘discerning picture-goers’, the impact of cinema was likely to be damaging, for films frequently dealt with ‘disagreeable’ subjects ...the more sordid aspects of life’. Consequently, New Zealand cinemagoers, young and old, required protection from these unsavoury features.61

According to the Times, movies were an inferior aesthetic experience compared with stage drama. In cinema, especially American cinema, ‘the mind was diverted from thinking to seeing, from a study to a spectacle....’ The ‘higher type of mind’ sought drama as a source for intellectual reflection. But the ‘common type’ required emotional satisfaction, mere passive entertainment of the senses, ‘untutored by introspective analysis’. From this perspective, there was a division between cinema and its more refined and culturally correct counterpart, stage drama. There was also a split between their respective audiences, the one large but unthinking, and the other, smaller but refined and thoughtful. Talkies, in the Times’ perception, possessed an immediate, visceral but superficial appeal to the senses, not the intellect. American films were especially guilty of this cultural crime, for they were initially aimed at the vast, psychologically callow congeries of humanity gathered in the great cities of the New World, the more especially as the perilous and picturesque experiences with natives have been succeeded by the viler perils and animalism of gangsters.'

What especially concerned the Times was the imminent threat to New Zealand youth presented by the ‘ethical standards of the lower grades of the New World’ insinuating themselves here by way of Hollywood movies. Thus vigilance was needed to ensure ‘the foul sewers of man’s lower nature are not paraded on the public screen’.

4. Racism also played a role in perceptions of American cinema during these formative interwar years. In 1936 the Attorney-General agonized over the alleged influence of Hollywood on the street culture of some young Maori. 'They

dress and act the part of ...[film] characters ...usually the characters of the wild west films. That the films do have a strong suggestive influence is thus clear and that this influence is in the direction of increasing crime is also clear.

The Film Censor’s files of that era contain letters complaining about the presence of negro music and negro actors in American musical films, which were especially popular in New Zealand with the arrival of ‘talkies’. W.W. Tanner, the censor in the 1930s, agreed with these complaints . In January 1931 he described how he dealt with such films: ‘he had blocked all of them’. According to Tanner, ‘the general public did not know what they had been protected from’, namely cabaret and other scenes set in ‘surroundings of low quality’. Other public officials also condemned Hollywood musicals as indecent. T.B. Strong, New Zealand's Director of Education in the late 1920s, blamed ‘Yankee cinematograph pictures’ for their ‘insidious influence on our young folk’. He told Wellington Girls’ College pupils and parents of his objection to cabaret sequences

which not only included an ‘unashamed exhibition of female nakedness’, but also contained slang ‘characteristic of the less-educated American.’

Below: Risque titles, risque costumes, temptresses, sexually chatged scenes, night-club and cabaret scenes -and, the horror! - black entertainers on-screen and alongside white actors.

Everything that W.W. Tanner, New Zealand's film censor from 1924 to 1938 detested about Hollywood movies can be seen in these images above and below: negro performers and musicians (especially those in scenes with whites), cabaret sequences, songs and dialogue with American slang, nudity, 'offensive' sexual behaviour. He even bannd the 1930 antiwar classic All Quiet on the Western Front and cut sceens from King Kong. Most of the films he cut or banned were American, not British, in origin.