The Monuments Men- recovering looted World War II art

"It used to be called plundering. But today things have become more humane. In spite of that, I intend to plunder, and to do it thoroughly."

Hermann Goring

Hermann Goring

George Clooney's upcoming The Monuments Men has a capable director, a great cast (Clooney, Cate Blanchett, Matt Damon, Bill Murray, John Goodman etc) and is based on the wartime exploits of an interesting but virtually unknown group: Frenchwoman Rose Valland who helped thwart Nazi plans to send looted French art to Germany and a team of art experts who job was to track down the places where looted art had been hidden by the Nazis. As author Robert Edsel has described in his book Monuments Men: Allied heroes, Nazi thieves and the greatest treasure hunt in history (London: 2009), approximately 350 men and women from several countries worked at various times for the U.S. Army unit known as the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Section (MFAA). Many of them were art historians and museum administrators and curators, whose expertise was essential in identifying the stolen objects and tracing the rightful owners. Others were chosen because of their fluency in languiages, especially German.Their job was to locate and return art works and historical documents that the Nazis had looted from public and private collections throughout Occupied Europe, a significant portion of the latter coming from Jewish sources. Eventually the Monuments Men restored over five million cultural artefacts.

It will be interesting to see if Clooney's movie can match the calibre of John Frankenheimer's 1964 The Train, which also features a character based on Rose Villand and the French Resistance's efforts to prevent a trainload of looted art being sent to Germany. Frankenheimer's movie is one of the best war / Resistance movies ever made: exciting, tense, and with a strong moral message.

It will be interesting to see if Clooney's movie can match the calibre of John Frankenheimer's 1964 The Train, which also features a character based on Rose Villand and the French Resistance's efforts to prevent a trainload of looted art being sent to Germany. Frankenheimer's movie is one of the best war / Resistance movies ever made: exciting, tense, and with a strong moral message.

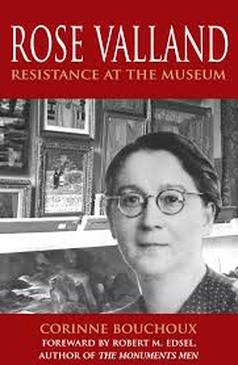

Rose Valland

A crucial contributor to the achievements of the 'Monuments Men' team was an unassuming, self-effacing Frenchwoman, Rose Valland (played in the movie by Cate Blanchett).Rose Valland (1898-1980), a product of small-town provincial France, did not come from the socially and educationally privileged elite that usually supplied Anglo-French museum and art curators. Before she gained gained several degrees in art history and fine arts, Valland had for a time tried life as a struggling artist in Paris. Unassuming, self-effacing, and rather plain and dour in appearance, she was working as an unpaid volunteer curator in Paris' Jeu de Paume gallery in the Tuileries Gardens when the Nazi Occupying forces took it over and used it as a depot to store artworks stolen from private French collections, mainly Jewish.

The quiet, efficient Valland, who concealed her German-speaking ability in order to eavesdrop, oversaw the steady accumulation of looted artworks. Her knowledge of shorthand helped her to carefully record what art was being stored and transferred, and its destination. She passed this information, which included details of which trains were carrying the plundered art to Germany, on to her contacts in the Resistance. Her main contact was Jacues Jaujard, Director of National Museums, who had established links with the Resistance. He gave Valland the dangerous job of secretly compiling, under the watchful eyes of German guards and supervisors, an inventory of all the art works the Nazis had deposited in the Jeu de Paume.Valland even copied negatives of the photos the Germans made of each item stored in the gallery. A typical message to Jaujard (3 January, 1943) told him that "75 bottles of champagne, 21 bottles of cognac, 16 Flemish and Dutch paintings left the Jeu de Palme at the request of M. Goring to celebrate his birthday." But all she could do after witnessing the burning, in the garden of the Jeu de Palme, of several hundred "degenerate" paintings by Picasso,Miro and others, was inform Jaujard "Impossible to save anything." [Alan Riding, And the Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris (London, 2011), p.166 ]

Her surreptitious role became even more important when under Hitler's orders, the Jeu de Paume became headquarters for the Special Staff for Pictorial Art, a section of the ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg), itself a unit of the Foreign Affairs Division of the Reich. Alan Riding, whose book on cultural life in Paris under the Occupation is essential reading for anyone interested in the period of Occupation and the Resistance, discusses Goring's visit to the Jeu de Paume in November, 1940

" he was stunned by what he saw, and what, in effect, he was being offered.

For Goring's inspection, the Jeu de Paume had been arranged like a nineteenth

century museum, with hundreds of paintings covering the walls of two floors,

plus a good many more displayed on the racks. "

Riding, And the Show Went On , p.162.

By late 1944 the Germans planned to get rid of their looted art and send it by train to Germany. Riding describes how Valland

" learned on August 1. 1944, that five cars of train No.40,044 were being

loaded with 148 cases of art ...tipped off the Resistance, which kept the train

from leaving Alnay, on the outskirts of Paris." Riding, p.167

The quiet, efficient Valland, who concealed her German-speaking ability in order to eavesdrop, oversaw the steady accumulation of looted artworks. Her knowledge of shorthand helped her to carefully record what art was being stored and transferred, and its destination. She passed this information, which included details of which trains were carrying the plundered art to Germany, on to her contacts in the Resistance. Her main contact was Jacues Jaujard, Director of National Museums, who had established links with the Resistance. He gave Valland the dangerous job of secretly compiling, under the watchful eyes of German guards and supervisors, an inventory of all the art works the Nazis had deposited in the Jeu de Paume.Valland even copied negatives of the photos the Germans made of each item stored in the gallery. A typical message to Jaujard (3 January, 1943) told him that "75 bottles of champagne, 21 bottles of cognac, 16 Flemish and Dutch paintings left the Jeu de Palme at the request of M. Goring to celebrate his birthday." But all she could do after witnessing the burning, in the garden of the Jeu de Palme, of several hundred "degenerate" paintings by Picasso,Miro and others, was inform Jaujard "Impossible to save anything." [Alan Riding, And the Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris (London, 2011), p.166 ]

Her surreptitious role became even more important when under Hitler's orders, the Jeu de Paume became headquarters for the Special Staff for Pictorial Art, a section of the ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg), itself a unit of the Foreign Affairs Division of the Reich. Alan Riding, whose book on cultural life in Paris under the Occupation is essential reading for anyone interested in the period of Occupation and the Resistance, discusses Goring's visit to the Jeu de Paume in November, 1940

" he was stunned by what he saw, and what, in effect, he was being offered.

For Goring's inspection, the Jeu de Paume had been arranged like a nineteenth

century museum, with hundreds of paintings covering the walls of two floors,

plus a good many more displayed on the racks. "

Riding, And the Show Went On , p.162.

By late 1944 the Germans planned to get rid of their looted art and send it by train to Germany. Riding describes how Valland

" learned on August 1. 1944, that five cars of train No.40,044 were being

loaded with 148 cases of art ...tipped off the Resistance, which kept the train

from leaving Alnay, on the outskirts of Paris." Riding, p.167

Goering paid 21 visits to the Jeu de Palme.

Valland's work was highly dangerous. The Jeu de Palme during Occupation was not a placid museum sub-branch: its activities were carried out under the watchful eyes of top Nazis, and the ERR itself was a privileged branch of Nazi officialdom. She was under constant surveillance; torture and either a death sentence or deportation to a concentration camp awaited her if her activities were discovered.In fact, she was warned that she could be shot if any 'indiscretion' was found. Her work on the task of saving, identifying and returning looted art works to their rightful owners continued after the end of the war. Valland worked in Germany from 1945-1951 on this project and on her return to France she continued her mission to trace and return stolen French art.

Yet the male-dominated, socially and academically privileged French art world barely acknowledged her contributions. Instead, she was criticised for working with the American Monument Men and for tirelessly pursuing the whereabouts of unrecovered stolen art - this caused considerable embarrassment for influential members of the postwar French cultural and political elite whose own compromises and greed were in danger of being exposed. A Louvre curator, Magdeleine Hours, later lamented that Valland

"received little understanding from her colleagues; she unleashed envy and passions, and we were few to show out admiration. On the day of her funeral at Les Invalides, the Director of the Musees de France administration, theChief Curator of the drawing department, and myself, with a few museum attendants, were practically the only ones present to show the respects that were due to her. This woman, who had risked her life so often and with such persistence, who had brought honor to the corps of curators and saved the property of so many collectors, was treated by many with indifference, if not hostility." (cited Edsel, Monuments Men, p.413)

Yet the male-dominated, socially and academically privileged French art world barely acknowledged her contributions. Instead, she was criticised for working with the American Monument Men and for tirelessly pursuing the whereabouts of unrecovered stolen art - this caused considerable embarrassment for influential members of the postwar French cultural and political elite whose own compromises and greed were in danger of being exposed. A Louvre curator, Magdeleine Hours, later lamented that Valland

"received little understanding from her colleagues; she unleashed envy and passions, and we were few to show out admiration. On the day of her funeral at Les Invalides, the Director of the Musees de France administration, theChief Curator of the drawing department, and myself, with a few museum attendants, were practically the only ones present to show the respects that were due to her. This woman, who had risked her life so often and with such persistence, who had brought honor to the corps of curators and saved the property of so many collectors, was treated by many with indifference, if not hostility." (cited Edsel, Monuments Men, p.413)

Monuments Men filming on location: Wexford air base, near London (left) and two Berlin locations.

The Monuments Men in historical context: World War II Looting of Art Works

The looting of art works from defeated nations or peoples by their conquerors has been a persistent feature of the aftermath of war. It has an unfortunately long history, as Ivan Lindsay, an art expert and dealer and formerly a British army officer, points out, noting that the Romans and Napoleon, among others, considered looting of valuables and artefacts as a normal process of war, even an excuse to go to war. He observes that in the eighth century BCE, Sargun II (from modern Syria), invaded most of the eastern Mediterranean and looted art works and religious statuary as well as gold, silver, and even musical instruments. From one temple alone in Musasit Sargun took "one ton of gold, five tons of silver, and 334,000 objects." A century later the King of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar II sacked Jerusalem, in the process enslaving its Jewish population and stealing all the gold lodged in the Temple of Solomon. The latter was put to use to rebuild Bablyon, including the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. During the 356-323 BCE Alexander the Great's prolonged campaigns depended on looted gold and silver from his conquered territories, especially great cities like Persepolis. http://www.ancient.eu.com/article/214/

Stephanie Goldfarb, an expert on the topic of cultural theft, points out that the Romans played an especially significant role in the annals of art theft. They "perpetuated the tradition of cultural plunder as a symbolic glorification of the conquering empire." Perhaps the most infamous example was the sack of Jerusalem in 70BCE and its destruction and pillaging of its Temple. The plunder was brought to Rome and the consequent enpormous procession of its booty can still be seen in the famous Arch of Titus.

In more 'recent' times, looting of cultural artefacts was carried out by the Crusaders, the Spanish conquistadores, and the seventeenth century Swedish father and daughter monarchs, Gustav Adolphus, who aimed to establish Stockholm as a great cultural center. However, his activities were outdone by Napoleon Bonaparte. He stripped Italy of many of his greatest artefacts: the huge bronze Four Horses of San Marco, Venice. Works stolen from Rome included the Laocoon, the Discobulus, the Medici Venus and the Discobulus. According to Goldfarb,

"Napoleon perpetuated a wide-scale systematic seizure of art which would surpass all art crime which had previously been perpetuated during war. Napoleon strove to model his own empire after that of the Romans and consequently embraced the Roman paradigm of wartime art looting. For Napoleon, looting was thus a declaration of triumph, as it had been for the Romans, but it was also a demonstration of his ideological goals. Napoleon imagined that he was founding a new empire to rival that of Rome, and sought to demonstrate the similarity (but also the superiority) of Napoleonic France to ancient Rome. In order to align himself with the Roman Empire, Napoleon not only embraced the Roman model of looting, but specifically sought to seize the treasures of the Roman Empire itself. For Napoleon, conquering Rome meant conquering a symbol of power....

Napoleonic cultural plunder was not confined to the Italian peninsula. Prussia, Vienna and Flanders provided other sources as well.This system of "state-sponsored looting" was bureaucratically organised, led by the Commission Temporaire de Arts, which issued lists of art works to be seized in invaded countries and cities.

The central repository for many of these artefacts was the Louvre. As Peter Brooks notes, at this time the Louvre (which opened during the Revolution's Reign of Terror) was "largely built on the systematic looting of Western Europe and Egypt, of which Napoleon made himself master." Under the supervision of the museum's Director, Dominique-Vivant Denon, appointed by Napoleon, the Louvre became what Brooks calls "the European capital of cultural artefacts", in which Napoleonic artistic spoils were centrally located for the education, moral and cultural improvement and enjoyment of the population, ranging from art connoisseurs, artists and the public at large. The collections, then, would not be available only to a select few; the people could participate as well.

Stephanie Goldfarb, an expert on the topic of cultural theft, points out that the Romans played an especially significant role in the annals of art theft. They "perpetuated the tradition of cultural plunder as a symbolic glorification of the conquering empire." Perhaps the most infamous example was the sack of Jerusalem in 70BCE and its destruction and pillaging of its Temple. The plunder was brought to Rome and the consequent enpormous procession of its booty can still be seen in the famous Arch of Titus.

In more 'recent' times, looting of cultural artefacts was carried out by the Crusaders, the Spanish conquistadores, and the seventeenth century Swedish father and daughter monarchs, Gustav Adolphus, who aimed to establish Stockholm as a great cultural center. However, his activities were outdone by Napoleon Bonaparte. He stripped Italy of many of his greatest artefacts: the huge bronze Four Horses of San Marco, Venice. Works stolen from Rome included the Laocoon, the Discobulus, the Medici Venus and the Discobulus. According to Goldfarb,

"Napoleon perpetuated a wide-scale systematic seizure of art which would surpass all art crime which had previously been perpetuated during war. Napoleon strove to model his own empire after that of the Romans and consequently embraced the Roman paradigm of wartime art looting. For Napoleon, looting was thus a declaration of triumph, as it had been for the Romans, but it was also a demonstration of his ideological goals. Napoleon imagined that he was founding a new empire to rival that of Rome, and sought to demonstrate the similarity (but also the superiority) of Napoleonic France to ancient Rome. In order to align himself with the Roman Empire, Napoleon not only embraced the Roman model of looting, but specifically sought to seize the treasures of the Roman Empire itself. For Napoleon, conquering Rome meant conquering a symbol of power....

Napoleonic cultural plunder was not confined to the Italian peninsula. Prussia, Vienna and Flanders provided other sources as well.This system of "state-sponsored looting" was bureaucratically organised, led by the Commission Temporaire de Arts, which issued lists of art works to be seized in invaded countries and cities.

The central repository for many of these artefacts was the Louvre. As Peter Brooks notes, at this time the Louvre (which opened during the Revolution's Reign of Terror) was "largely built on the systematic looting of Western Europe and Egypt, of which Napoleon made himself master." Under the supervision of the museum's Director, Dominique-Vivant Denon, appointed by Napoleon, the Louvre became what Brooks calls "the European capital of cultural artefacts", in which Napoleonic artistic spoils were centrally located for the education, moral and cultural improvement and enjoyment of the population, ranging from art connoisseurs, artists and the public at large. The collections, then, would not be available only to a select few; the people could participate as well.

|

|

Nazi Art Theft

Hitler surveying a model of his planned Linz cultural center.

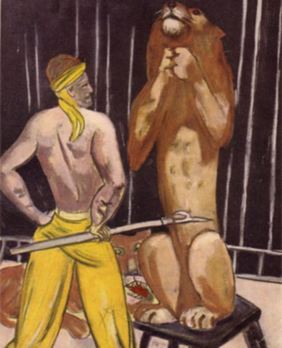

Stephanie Goldfarb notes that "as under Napoleon, Nazi art looting was state-sponsored, but the nazis took it to an entirely new level." It began as the destruction of so-called 'degenerate' art and the confiscation of Jewish cultural treasures in Germany, then spread to the occupied territories of Europe, including Poland, France, Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands (worth an estimated 21-22 billion US dollars today). Many of the art works were intended for the private collections of Hitler and Goering, and other top Nazis. Others were earmarked for Hitler's planned Fuhrermuseum in Linz, Austria, his adopted home town, and the burial place of his parents. Hitler intended to rebuild Linz as a magnificent cultural center housing the finest art museum in the world, crammed with art treasures taken from all over Europe.

Not only did the scale and value of Nazi cultural looting surpass all other examples in history. It was also unique in its ideologically-based religious and ethnic motivation: a form of cultural 'cleansing' of the cultural heritage of what the Nazis deemed to be 'inferior' races and cultures. The Nazi state apparatus even set up a special unit headed by Alfred Rosenberg for 'acquiring' art objects - the Einsatzstan Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR). The Nuremberg Tribunal condemned Rosenberg to death for, among other crimes, his part in what it called "a system of orgnaised plunder of both public and private property throughout the invaded countries of Europe."

See Goldfarb's 'Lessons in Looting', http://art-crime.blogspot.co.nz/2009/07/lessons-in-looting.html

Not only did the scale and value of Nazi cultural looting surpass all other examples in history. It was also unique in its ideologically-based religious and ethnic motivation: a form of cultural 'cleansing' of the cultural heritage of what the Nazis deemed to be 'inferior' races and cultures. The Nazi state apparatus even set up a special unit headed by Alfred Rosenberg for 'acquiring' art objects - the Einsatzstan Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR). The Nuremberg Tribunal condemned Rosenberg to death for, among other crimes, his part in what it called "a system of orgnaised plunder of both public and private property throughout the invaded countries of Europe."

See Goldfarb's 'Lessons in Looting', http://art-crime.blogspot.co.nz/2009/07/lessons-in-looting.html

Photo left above shows a U.S. soldier, Corproal Donald Omitz, examining a painting recovered from storage in a German mine; above centre shows a soldier sorting stolen Hebrew and Jewish documents stolen from synagogues etc.; right: two members of the Monuments Men team examine paintings found in a German mine.

Photos from U.S. National Archives Records (Holocaust-Era Assets: Records Relating to Nazi Gold: Greg Bradsher)

Photos from U.S. National Archives Records (Holocaust-Era Assets: Records Relating to Nazi Gold: Greg Bradsher)

Above left: looted Rembrandt portrait recovered in MUnich, 1945; Right: one of the Monuments Men examining rescued Italian art.

The movie correctly refers to the roles of President Roosevelt and also General Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, in establishing the Monuments Men team. Illustration left shows Eisenhower and General Patton inspecting art rescued by the Monuments men team.

The crucial Eisenhower order mentioned in the film was in fact issued only eleven days before the D-Day invasion:

"Shortly we will be fighting our way across the Continent of Europe in battles designed to preserve our civilization. Inevitably, in the path of our advance will be found historical monuments and cultural centers which symbolize to the world all that we are fighting to preserve.

It is the responsibility of every commander to protect and respect these symbols whenever possible.

In some circumstances the success of the military operation may be prejudiced in our reluctance to destroy these revered objects. Then, as at Cassino, where the enemy relied on our emotional attachments to shield his defense, the lives of our men are paramount. So, where military necessity dictates, commanders may order the required action even though it involves destruction to some honored site.

But there are many circumstances in which damage and destruction are not necessary and cannot be justified. In such cases, through the exercise of restraint and discipline, commanders will preserve centers and objects of historical and cultural significance. Civil Affairs Staffs at higher echelons will advise commanders of the locations of historical monuments of this type, both in advance of the frontlines and in occupied areas. This information, together with the necessary instruction, will be passed down through command channels to all echelons."

The crucial Eisenhower order mentioned in the film was in fact issued only eleven days before the D-Day invasion:

"Shortly we will be fighting our way across the Continent of Europe in battles designed to preserve our civilization. Inevitably, in the path of our advance will be found historical monuments and cultural centers which symbolize to the world all that we are fighting to preserve.

It is the responsibility of every commander to protect and respect these symbols whenever possible.

In some circumstances the success of the military operation may be prejudiced in our reluctance to destroy these revered objects. Then, as at Cassino, where the enemy relied on our emotional attachments to shield his defense, the lives of our men are paramount. So, where military necessity dictates, commanders may order the required action even though it involves destruction to some honored site.

But there are many circumstances in which damage and destruction are not necessary and cannot be justified. In such cases, through the exercise of restraint and discipline, commanders will preserve centers and objects of historical and cultural significance. Civil Affairs Staffs at higher echelons will advise commanders of the locations of historical monuments of this type, both in advance of the frontlines and in occupied areas. This information, together with the necessary instruction, will be passed down through command channels to all echelons."

The significance of Cassino for the Monuments Men team

Most accounts of the reasons behind the formation of the Monuments Men overlook the significance of the Allied forces struggle to capture the vital strategic Italian Monte Cassino monastery, on a 500 foot high hill which overlooked the narrow Liri Valley through which the Allied forces had to pass to enter northern Italy. Crack German forces had taken over the 1400 year-old Benedictine monastery, which for centuries had been the depository of invaluable religious works of art. They turned its environs into an almost impregnable fortress, setting up fields of fire, minefields, fortifications and demolishing stopbanks to flood strategic areas.

Allied forces, including the [free] Polish Army and the New Zealand Division, plus its Maori Battalion, attacked repeatedly. Unaware that the Germans had shrewdly deployed their forces in the much more defensible zone outside the monastery, they called in airstrikes which eventually demolished the Monastery. Not a single German soldier was killed. The ruins simply provided more defensible positions. Consequently, the eventual capture of the site came at considerable Allied cost.

Nazi and Italian Fascist propaganda claimed that the Allies had wilfully destroyed the irreplaceable art works, a lie that is still repeated in some accounts of the battle. In fact, Eisenhower had months earlier ordered that as far as possible Allied forces must "endeavour to protect all Italian monuments." For weeks Allied commanders refused to attack the Cassino directly for fear of being labelled cultural vandals, with the result that troops and their loved ones increasingly claimed that Allied men were being sacrificed in order to protect cultural artefacts. However, the Axis propaganda portraying the Allies as uncouth barbarians may well have influenced the decison to set up the Monuments men team.

What the Allies failed to realise until too late was that, with the exception of some frescoes on walls, all the invaluable cultural artefacts had been safely removed from the Monastery some months before the battle. Under the supervision of Oberstleutnant Julius Schagel, a hundred trackloads of art, statues manuscripts and books - and the remains of St. Benedict - accompanied by monks from the Abbey, were transferred to Rome. The Reich Propganda Division filmed the transfer in detail. It was the subject of one of their weekly newsreels, Die Deutsche Wochschau, shown in German cinemas in February 1944.

Ironically, fifteeen cases of artworks from Cassino were looted by the Hermann Goering division and sent to him as a birthday present.

One of the Monuments Men, Thomas Howe, worked after the war at cataloguing and restoring both the looted art and the artefacts removed from the

Monastery to Rome.

Allied forces, including the [free] Polish Army and the New Zealand Division, plus its Maori Battalion, attacked repeatedly. Unaware that the Germans had shrewdly deployed their forces in the much more defensible zone outside the monastery, they called in airstrikes which eventually demolished the Monastery. Not a single German soldier was killed. The ruins simply provided more defensible positions. Consequently, the eventual capture of the site came at considerable Allied cost.

Nazi and Italian Fascist propaganda claimed that the Allies had wilfully destroyed the irreplaceable art works, a lie that is still repeated in some accounts of the battle. In fact, Eisenhower had months earlier ordered that as far as possible Allied forces must "endeavour to protect all Italian monuments." For weeks Allied commanders refused to attack the Cassino directly for fear of being labelled cultural vandals, with the result that troops and their loved ones increasingly claimed that Allied men were being sacrificed in order to protect cultural artefacts. However, the Axis propaganda portraying the Allies as uncouth barbarians may well have influenced the decison to set up the Monuments men team.

What the Allies failed to realise until too late was that, with the exception of some frescoes on walls, all the invaluable cultural artefacts had been safely removed from the Monastery some months before the battle. Under the supervision of Oberstleutnant Julius Schagel, a hundred trackloads of art, statues manuscripts and books - and the remains of St. Benedict - accompanied by monks from the Abbey, were transferred to Rome. The Reich Propganda Division filmed the transfer in detail. It was the subject of one of their weekly newsreels, Die Deutsche Wochschau, shown in German cinemas in February 1944.

Ironically, fifteeen cases of artworks from Cassino were looted by the Hermann Goering division and sent to him as a birthday present.

One of the Monuments Men, Thomas Howe, worked after the war at cataloguing and restoring both the looted art and the artefacts removed from the

Monastery to Rome.

Above left image shows how the Monastery site commanded the strategic valley below. All three images show the extent of the destruction caused by the American Air Force's bombing.

Below left: German soldiers unload trucks containing art and artefacts taken from Cassino .

Below right: American trucks returning looted art works to Florence get a civic reception.

Below left: German soldiers unload trucks containing art and artefacts taken from Cassino .

Below right: American trucks returning looted art works to Florence get a civic reception.

Newly discovered evidence of Nazi art thefts emerge just weeks before movie's premiere

In early November, 2013, German authorities announced the discovery in Munich of a hoard of some 1500 art works looted during the Nazi era, including works by Matisse, Chagall and Picasso, as well as other from previous centuries, with an estimated total value of about a billion Euros. Some of the paintings have never before been seen.The cache was hidden for over six decades in a disheveled apartment owned by reclusive octogenarian Cornelius Gurlitt, son of influential pre-war art dealer Hildebrandt Gurlitt who helped Nazis acquire looted art works. Part of the hoard consists of works shown at the notorious 1937 Exhibition of Degenerate Art. Others were either seized from Jewish owners or were sold by them under duress at ridiculously low prices. The invaluable collection was actually discovered by Bavarian customs police in February, 2011, but their recovery was not announced at that time. Officially, this was in order to allow authorities time to try to solve the vexed problem of deciding legal ownership of the paintings. but already allegations of a coverup are emerging. Cornelius Gurlitt has apparently vanished.