Hangmen Also Die

(Fritz Lang, 1943)

Within a few days of the news that Reinhold Heydrich, Hitler's governor of the occupied nation of Czechoslovakia, had died of complications after a daring roadside assassination attempt, two famous emigres from Nazi Germany met in Hollywood to discuss making a film based on the events. One of the pair was Fritz Lang, the famousGerman Expressionist film-maker, director of such classics as M and Metropolis in Germany, and Fury in the USA.. The other was a recent German emigre: Bertolt Brecht, the most famous of Europe's dramatists, one of the twentieth century's leading literary theorists and a fine poet and lyricist. Brecht, a fervent Communist of Stalinist sympathies, had already written some of the twentieth century's most innovative plays, such as The Threepenny Opera, Baal and Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. Both Brecht and Lang had been forced to flee Nazi Germany. Brecht was endangered by his communist sympathies; Lang had a Jewish mother. The artistic innovations and content of both men's work was regarded as 'decadent' and 'unGerman' by the Nazi cultural establishment.

Above left: Fritz Lang and Bertolt Brecht. Above right shows Lang [centre] on set with the great cinematographer James Wong Howe and H.H. von Twardowski, who played the role of Heydrich in the movie.

The Making of Hangmen Must Die

Although Land and Brecht agreed that the Heydrich assassination provided possibilities for a worthwhile movie, and the pair initially worked on a script, their relationship was contentious and controversial. This was hardly surprising. Although Lang had helped financially and otherwise in arranging for the playwright to obtain safe haven in America, conflict was probably inevitable. Both men had irascible and domineering personalities. Although both belonged to the political left, Lang did not share Brecht's communist beliefs. Lang had already spent some years working within the restrictions of Hollywood's studio system ( and would spend another decade or so there). He disliked that system, and felt stifled by it, but circumvented it when he could. Brecht, brashly condemned Hollywood and America as soon as he arrived; Brecht, profoundly ungrateful by nature, despised America and constantly complained about his housing, his finances and the U.S. authorities' suspicions of his communist views.. For him, Hollywood was epitomised capitalism at its worst, a sordid merchant of false values and moral decadence that distracted the masses from realising their economic and social exploitation. Even worse for Brecht, Hollywood completely failed to appreciate what he regarded as his enormous artistic talent and cultural genius. Brecht also regarded Lang as having sold out to Hollywood. As early as 1937 Brecht wrote to his then wife Lotte Lenya that

“Lang makes you want to puke. Nobody in the whole world is as important as he imagines himself to be. I completely understand why he is so hated everywhere.” Yet the monocled and disdainful Lang not only helped support and finance Brecht's move from Europe to the USA. He also offered Brech the chance to work on a script as a means of helping the author's finances.

Unsurprisingly, the pair's collaboration on this script (they initially called it "the hostage story") about the assassination became increasingly tense and eventually ended in discord, with Brecht making an unsuccessful claim to Hollywood's Screenwriters Guild over credit for the final script. Ironically, the screenplay credit was given to another Communist: the American screenwriter John Wexley, who was blacklisted for his communist views in the McCarthy era.

Although Land and Brecht agreed that the Heydrich assassination provided possibilities for a worthwhile movie, and the pair initially worked on a script, their relationship was contentious and controversial. This was hardly surprising. Although Lang had helped financially and otherwise in arranging for the playwright to obtain safe haven in America, conflict was probably inevitable. Both men had irascible and domineering personalities. Although both belonged to the political left, Lang did not share Brecht's communist beliefs. Lang had already spent some years working within the restrictions of Hollywood's studio system ( and would spend another decade or so there). He disliked that system, and felt stifled by it, but circumvented it when he could. Brecht, brashly condemned Hollywood and America as soon as he arrived; Brecht, profoundly ungrateful by nature, despised America and constantly complained about his housing, his finances and the U.S. authorities' suspicions of his communist views.. For him, Hollywood was epitomised capitalism at its worst, a sordid merchant of false values and moral decadence that distracted the masses from realising their economic and social exploitation. Even worse for Brecht, Hollywood completely failed to appreciate what he regarded as his enormous artistic talent and cultural genius. Brecht also regarded Lang as having sold out to Hollywood. As early as 1937 Brecht wrote to his then wife Lotte Lenya that

“Lang makes you want to puke. Nobody in the whole world is as important as he imagines himself to be. I completely understand why he is so hated everywhere.” Yet the monocled and disdainful Lang not only helped support and finance Brecht's move from Europe to the USA. He also offered Brech the chance to work on a script as a means of helping the author's finances.

Unsurprisingly, the pair's collaboration on this script (they initially called it "the hostage story") about the assassination became increasingly tense and eventually ended in discord, with Brecht making an unsuccessful claim to Hollywood's Screenwriters Guild over credit for the final script. Ironically, the screenplay credit was given to another Communist: the American screenwriter John Wexley, who was blacklisted for his communist views in the McCarthy era.

To Brecht's annoyance, Lang made Hangmen as a film noir which used Heydrich's assassination to focus on the noirish elements of betrayal, complicity and intrigue, set within a claustrophobic atmosphere of intrigue and menace. Lang wanted tension and audience interest in the fates of the characters. As in many of his films, he observes the struggles of people under threat from overpowering forces. The superb cinematography of James Wong Howe emphasises shadows and darkness, and highlight individuals trapped in a confined situation.

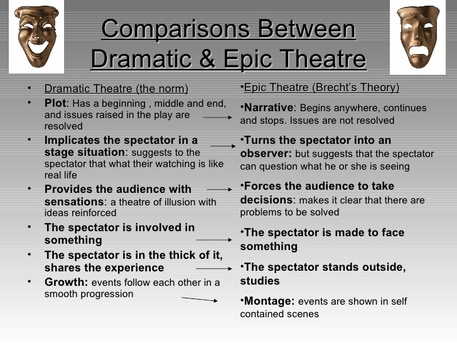

But Brecht wanted overt and artificial political statements. For him tension and viewer identification with characters diverted attention from political messages. Brecht wanted the movie to portray the Resistance movement as part of a mass 'people's uprising' against fascist rule. Lang, more realistically, downplayed this political aspect, and insisted on focussing on a sense of entrapemnt , as (fictional) individuals desperately trying to escape overwhelmingly powerful oppressive forces. Brecht regarded this approach as melodramatic. Lang saw Brecht's stance as emphasising Marxist platitudes at the expense of tension and audience interest. Brecht of course didn't want the audience to become intensely involved with the movie. Instead they should be detached observers puzzling out a political message. Lang wanted to make a successful box-office Hollywood thriller with an anti-Nazi message. He hoped to stir the emotions, Brecht aimed to stimulate the intellect.

The image below [source unknown], although based on stage theatre, conveniently sums up the differences between Lang's approach (dramatic theatre) and Brecht's approach (Epic theatre) to cinematic drama:

But Brecht wanted overt and artificial political statements. For him tension and viewer identification with characters diverted attention from political messages. Brecht wanted the movie to portray the Resistance movement as part of a mass 'people's uprising' against fascist rule. Lang, more realistically, downplayed this political aspect, and insisted on focussing on a sense of entrapemnt , as (fictional) individuals desperately trying to escape overwhelmingly powerful oppressive forces. Brecht regarded this approach as melodramatic. Lang saw Brecht's stance as emphasising Marxist platitudes at the expense of tension and audience interest. Brecht of course didn't want the audience to become intensely involved with the movie. Instead they should be detached observers puzzling out a political message. Lang wanted to make a successful box-office Hollywood thriller with an anti-Nazi message. He hoped to stir the emotions, Brecht aimed to stimulate the intellect.

The image below [source unknown], although based on stage theatre, conveniently sums up the differences between Lang's approach (dramatic theatre) and Brecht's approach (Epic theatre) to cinematic drama:

|

|

|