Hemingway & Gellhorn

Nicole Kidman and Clive Owen in Philip Kaufman's movie Hemingway & Gellhorn

[Photo: Karen Ballard / HBO]

Hemingway & Gellhorn: the Background to the Movie

|

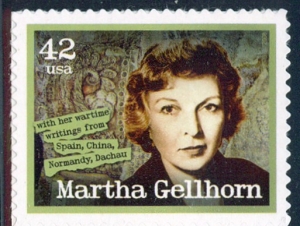

Despite the fascinating nature of Hemingway's life and times, few movies have been made about him, although his fictional work has frequently been adapted for the screen. And until 2012's HBO movie Hemingway & Gellhorn, no movie has been made about Martha Gellhorn.She was his third wife (an author and journalist herself) and for several years his companion on some of Hemingway's most interesting excursions into the battle zones of civil war Spain -a crucial setting in the movie - and World War 2, including China, Normandy and the liberation of Paris. Hemingway had divorced his previous two wives, but it was the feisty Gellhorn who divorced Hemingway and went on to have a long and distinguished career in journalism. Their fraught relationship is the subject of Philip Kaufman's movie.

|

Who was Martha Gellhorn?

"My whole memory of sex with Ernest is the hope that it would soon be over" - Martha Gellhorn

Although Gellhorn, an abrasively honest woman, described herself as "the worst bed partner in five continents", she had other attributes that appealed immediately to Hemingway when the pair met at Sloppy Joe's bar in Key West, Florida in 1936. Her initial impression of the writer was of "a large durty man in somewhat soiled white shorts and shirt." She decribed him as "an odd bird, very lovable and full of fire and a marvellous story teller (in a writer this is imagination, in anyone it's lying)." Hemingway was soon letting Gellhorn read the mss of his latest book and telling her "fine stories about Cuba and the hurricane." [Caroline Moorehead (ed), Selected Letters of Martha Gellhorn (New York: 2006), pp.44-45]

Although Hemingway & Gellhorn depicts them as having wild, passionate and frequent sex, in fact physical attraction appears to have been relatively unimportant in their relationship. Instead, Gellhorn's feisty spirit, sense of adventure, ability to drink, and refusal to be overawed by the author and his reputation attracted him. Like Hemingway she was a journalist and a novelist , although these attributes eventually became a source of conflict. At the time of this 1936 meeting she was about to go to Spain to report on the Civil War for Colliers magazine, a coveted assignment and in those days a rare feat for a woman reporter to work in such a dangerous war zone.

Although still married to Pauline Pfeiffer (see below), Hemingway both impressed by, and jealous of, Gellhorn's audacity, arranged his own assignment and joined her in Spain. This started a romance that resulted in Gellhorn becoming temporaily infatuated with the author. Thus at the start of 1940 she signed a "Guaranty" (three in fact) to "Mr Warp Dimpy Gellhorn Bong Hemmy" in which she promised "always to express the appreciation I truly feel for everything he does for me, gives to me and means to me." She also promised "not to divorce [Hemingway] ... not for nobody, only he has to be a good boy too and not love nobody but me." Presciently, she added "But he will not love nobody but me." [Caroline Moorehead (ed), Selected Letters of Martha Gellhorn (New York: 2006), pp. 80-81]

Some months later Hemingway obtained a divorce from Pfeiifer. But the Hemngway-Gellhorn relationship was fiery; each was an intemperate egoist with a fine eye for the glamour and commercial cachet that their marriage brought. Both were advocates for the Republican side in the war. Initially the pair were not the celebrated celebrity reporting couple in Spain. That honour for a time belonged to two remarkable people, Gerda Taro and Robert Capa. Gerda has been completely erasied from the Hemingway & Gellhorn movie, although her glamorous persona, intrepid reporting of events, romance with Capa and death on the battlefield overshadowed Gellhorn. Capa has fared better in the history of war correspondents, but the neglect of Taro has continued.

Like Toro, Gellhorn openly mocked what she called "that objectivity shit" in her reporting. She learnt some writing skills from Hemingway, but he soon became uneasy with his protege's increasing reputation as an intrepid reporter . He also disliked her co-equal status with him as a public couple.

The pair quarreled with increasing frequency and bitterness: "Are you a war correspondent our wife in bed?" Hemingway demanded. Gellhorn told a friend that "My whole memory of sex with Ernest is the hope that it would soon be over". Both were serially unfaithful; Gellhorn had at least one abortion. Eventually Gellhorn decided to answer Hemingway's question in emphatic fashion. She left him to go to Finland to report on the imminent Russian invasion. Then she went to most theaters of the war, including the Far East. Hemingway reluctantly accompanied her to observe action in the Sino-Japanese conflict, but the relationship was over and both knew it.

In 1944 Hemingway was drinking heavily and injured himself in a car accident. He had also become friendly with another journalist, Mary Welsh. Martha divorced him and continued her journalistic career, focusing on war zones. She got ashore at Normandy as a stretcher bearer, went on Allied bombers over Berlin, and was one of the first reporters to enter Dachau. After 1945 she reported on conflicts in Indo-China, the Middle East and, when aged 81, Panama. By 1950 she was decribing her marriage to Hemingway as "slavery", insisting that he had "grown more and more like a maniac.....I hated his toughness, because I know it for what it is.... a pose to get away with being nasty, and ungenerous...." Gellhorn claimed that Hemingway had regarded her "as the woman he wanted , which meant which meant the woman he intended absolutely to own, crush, eat alive." [Caroline Moorehead (ed), Selected Letters of Martha Gellhorn (New York: 2006), pp. 210]

After divorcing Hemingway, Gellhorn married a Time editor in 1954; the marriage ended in divorce nine years later. She adopted an Italian boy from an orphanage in 1949, eventually leaving him in the care of others while she carried on her journalistic travels, to the embitterment of the relationship. Later in life she became almost blind, the result of a botched cataract operation. Gellhorn died by her own hand in 1989, aged almost 90.

For more about Martha Gellhorn, click here.

|

|

|

Other Women in Hemingway's Life

Agnes von Kurowski

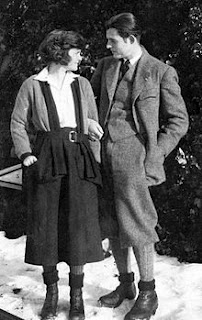

Agnes von Kurowski and Hemingway.

In June, 1918, days before his nineteenth birthday, Hemingway, who was serving with the Red Cross as an ambulance driver, was driving a mobile canteen when he was severely wounded by Austrian mortar fire and then by machine-gun fire as he carried a wounded Italian soldier to safety. During the six months that he spent recovering in a Milan hospital, Hemingway met Agnes von Kurowski, who was a Red Cross nurse there. She was seven years older than Hemingway, who became infatuated by her. However, Agnes, although fond of Hemingway was considerably less passionate. Her letters show that she was determined to pursue her nursing career and see more of life rather than become too emotionally involved with a youth she significantly nicknamed 'Kid'. She eventually wrote to the lovestruck Hemingway making it clear that the unconsummated relationship would go no further. Hemingway was upset and bitter over his rejection. A few years later he used Agnes in his second novel A Farewell to Arms as the model for Catherine Barkley, an English nurse who has a doomed relationship with Frederic Henry, a US soldier made impotent by his wounds. A fictionalized version of her also appears in The Snows of Kilimanjaro. Twice married, Agnes died aged 92 in 1984.

|

In Love and War was a 1996 film directed by Richard Attenborough. Many aspects of its depiction of the Hemingway-von Kurowsky relationship are fictional, especially in its depiction of the intensity of the relationship from Agnes' viewpoint. The film's inaccuracies are not redeemed by its acting or direction. It is best described as turgid.

|

Hadley Richardson

|

In his superb account of his 'Paris years', A Moveable Feast, written decades after he left his wife Hadley for the opportunities, financial and other, offered by the socialite-journalist Pauline Pfeiffer, Hemingway wrote of Hadley that she was

"the only one . . . who came well out of it finally and married a much finer man than I ever was or could ever hope to be and is happy and deserves it and that was one good and lasting thing that came out of that year". . Hemingway met Hadley Richardson after his return to the USA from hospitalization in MIlan and his rather one-sided romance with Agnes von Kurowski. Of his four wives, Hadley is especially important because she married Hemingway before he became the literary and media celebrity "Hemingway". Hadley was eight years older than the aspiring author [ a parallel here with Agnes' age] when they met in Chicago in 1920 at a party. She had a remarkable resemblance to Hemingway's mother. Her own protective mother had recently died; her father had earlier committed suicide. Like Hemingway, Richardson was prone to fits of deep depression. The pair quickly developed a relationship and married in September, 1921. Hadley's small income from a trust fund enabled Hemingway, always reluctant to augment income with any work other than writing or racetrack gambling, to go to Paris. Hadley not only provided money; she also wholeheartedly supported Ernest's literary endeavors. In Paris she did a remarkably competent job of seeing to Hemingway's culinary and domestic needs, as well as helping him fight his fits of depression. But some in Hemingway's circle of 'friends' among the American cultural expatriates regarded her as dull, quiet and conventional. Gradually he moved into the orbit of narcissistic intellectuals and celebrities -the Fitzgeralds, Gertrude Stein, Gerald and Sara Murphy, detaching himself from the calming and supportive influence of his wife. She astutely rejected them as poseurs: "I think I wanted something real". Encouraged by people like the Murphys, Hemingway blatantly carried on an affair with the very rich Pauline Pfeiffer, a Vogue editor. He was obviously seeking a divorce; Hadley eventually obliged. Her second marriage - to a journalist - was happier and longer; it lasted forty years. For Hemingway the end of the marriage meant that how worst features, such as his bullying, self-regard, and a determination to be the center of attention, now became increasingly prominent. His journey towards the loss of creative power and passion had begun.Towards the end of his life Hemingway finally admitted what the loss of Richardson meant to him: "I wish I had died before I ever loved anyone but her". |

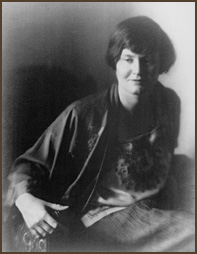

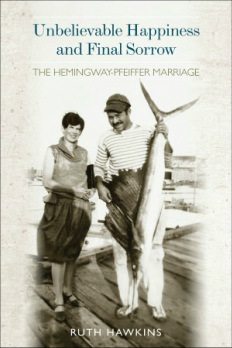

Pauline Pfeiffer -the second wifePfeiffer, born in 1895, came from a family that had made fortune in pharmaceuticals and land. During the war years she studied journalism at the University of Missouri (an unusual choice of subject for a woman in those days, and became a journalist, eventually working in New York, supported by a large allowance and with the luxury of her own family-provided apartment. She gained a job with Vanity Fair as fashion reporter, and then moved to Paris to work for Vogue. She and her sister immediately became much of the American 'ex-pat set' made famous by Fitzgerald and later Hemingway. At first Hemingway was more interested in her sister. Pauline became friends with Hadley, while carrying on an increasingly intense relationship with Hemingway. Ruth Hawkins' recent study of the relationship makes it clear that Hemingway was well aware of the monetary, social and leisure advantages presented by the Pfeiffer family's wealth and social cachet.The pair openly flaunted their relationship, successfully provoking Hadley into divorcing him.

The two married and returned to America, where Hemingway made full use of the Pfeiffer family's money to support his increasingly profitable writing, extensive travel, heavy drinking and expensive recreational pursuits such as big-game fishing. The marriage produced two sons. A grandson, Sean, has revamped the latest edition of Hemingway's A Moveable Feast to give their mother a more favorable portrayal. In the original edition Pfeiffer is depicted as entangling a gullible Hemingway into a relationship. The grandson includes a new section of the original draft in which Hemingway describes "the unbelievable happiness" he found in the relationship and admits culpability in the breakup of his marriage to Hadley. In 1937 Hemingway went to Spain to report on the Civil War, and found another woman - Martha Gellhorn. |

Mary Welsh: the last wife

|

In 1940 Mary Welsh, a journalist with Time magazine's European staff in Paris arrived in London after the fall of France to report on the war. Already divorced, she married an Australian journalist. Then in 1944 she met Hemingway, who was then recovering from a serious road accident. Martha showed scant sympathy, Mary offered sympathy and comfort. She accompanied him on his exploits in Europe after D-Day, in which Hemingway if you believe his accounts, landed on the beaches and played an active part in liberating Paris. Hemingway became infatuated with her:

"Funny how it should tasks one war to start a woman in your damn heart and another to finish her. Bad luck." The pair married the next year after Mary's second divorce. She was the only one of Hemingway's wives not to have come from St.Louis. Mary's role for the rest of Hemingway's life was to act as his companion, comforter and protector. His physical and mental health was declining sharply; he was overweight, alcoholic, diabetic, in pain from various injuries and his creative powers were waning. She lacked Gellhorn's journalistic abilities and zeal and offered no threat of competition to Hemingway as a writer. She was apparently quite content to look after Hemingway's needs although his increasing depression proved ultimately unconquerable. |

|

|