Silence of the Sea (Le silence de la mer)

Dir: Jean-Pierre Melville

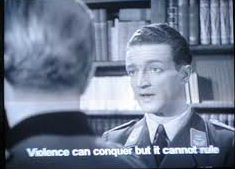

"Violence can conquer but it cannot rule"

Melville's 1947 examination of war and resistance

What's it about?

Many spoilers follow.

Jean-Pierre Melville's 1948 movie uses the German occupation of France during the second world war to examine the question of how violence and evil must be resisted. Yet only a few seconds of the film show scenes of war and for the most part the events of the film occur within one room in a small house (which belonged to 'Vercors', the author of the short novel on which La silence de la mer is based and himself a former Resistance member). 'Vercors' ( the name of a mountainous region in south-east France) was the psuedonym of Jean Bruller, a journalist-illustrator. The film closely follows the novella. Interestingly, the idea of a morally decent German officer billeted in a French home in a provincial town was used by Irene Nemirovsky in the French Jewish author's then unpublished second volume of her novel Suite Francaise. (She was arrested, and died in Auschwitz. The two volumes (of a planned five) were published to acclaim in 2004). [Alan Riding, And the Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris (London: 2011), pp.275-8]

The movie, like the book, is about the nature of resistance, in particular resistance to the Germans, but the actual Resistance movement plays no part in Le silence de la mer. And although the film is strongly anti-Nazi, a German officer ultimately emerges as a heroic figure.

Most of the film is set in the sitting-room of a small house in a rural town. A wounded German officer, has been billeted with the two occupants of the house - a man in his sixties and his niece, in her early twenties. Opposed to the German and what he stands for, the pair decide to resist him and what he represents: they do not speak to him at all for the month that he stays there. Nor do they look at him. (The uncle provides ocasional voice-over comments). The officer, Werner von Ebbrenac, is constantly polite, considerate and friendly. Every evening he talks to the pair, although they never respond. he talks about his love of music and literature, and about his personal beliefs. He tells the unresponsive couple how much he admires France and its literary culture, just as he admires Germany's musical culture. He expresses the hope that the two cultures will merge. France,he maintains, can help to overcome the vicious and violent elements that he acknowledges in German life. "I wish you a good evening" he says each night at the end of his monologue.

Towards the end of the film the setting changes. The officer goes to Paris, a city he admires, and visits its great landmarks. He meets some fellow German officers.To his dismay they do not share his vision of France; instead, they deplore French culture as depraved, corrupt and in need of Germanic 'purification'. He realises that they represent what Nazi Germany and the German army really are - brutalizing forces of domination. Von Ebbrenac knows that he had been in denial, that his role as a German officer makes him a complicit element in an evil institution.

When von Ebbrenac returns to the couple's house, he tells them that he is leaving to return to the war. He has asked to be sent to "hell": the Russian front.

Jean-Pierre Melville's 1948 movie uses the German occupation of France during the second world war to examine the question of how violence and evil must be resisted. Yet only a few seconds of the film show scenes of war and for the most part the events of the film occur within one room in a small house (which belonged to 'Vercors', the author of the short novel on which La silence de la mer is based and himself a former Resistance member). 'Vercors' ( the name of a mountainous region in south-east France) was the psuedonym of Jean Bruller, a journalist-illustrator. The film closely follows the novella. Interestingly, the idea of a morally decent German officer billeted in a French home in a provincial town was used by Irene Nemirovsky in the French Jewish author's then unpublished second volume of her novel Suite Francaise. (She was arrested, and died in Auschwitz. The two volumes (of a planned five) were published to acclaim in 2004). [Alan Riding, And the Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris (London: 2011), pp.275-8]

The movie, like the book, is about the nature of resistance, in particular resistance to the Germans, but the actual Resistance movement plays no part in Le silence de la mer. And although the film is strongly anti-Nazi, a German officer ultimately emerges as a heroic figure.

Most of the film is set in the sitting-room of a small house in a rural town. A wounded German officer, has been billeted with the two occupants of the house - a man in his sixties and his niece, in her early twenties. Opposed to the German and what he stands for, the pair decide to resist him and what he represents: they do not speak to him at all for the month that he stays there. Nor do they look at him. (The uncle provides ocasional voice-over comments). The officer, Werner von Ebbrenac, is constantly polite, considerate and friendly. Every evening he talks to the pair, although they never respond. he talks about his love of music and literature, and about his personal beliefs. He tells the unresponsive couple how much he admires France and its literary culture, just as he admires Germany's musical culture. He expresses the hope that the two cultures will merge. France,he maintains, can help to overcome the vicious and violent elements that he acknowledges in German life. "I wish you a good evening" he says each night at the end of his monologue.

Towards the end of the film the setting changes. The officer goes to Paris, a city he admires, and visits its great landmarks. He meets some fellow German officers.To his dismay they do not share his vision of France; instead, they deplore French culture as depraved, corrupt and in need of Germanic 'purification'. He realises that they represent what Nazi Germany and the German army really are - brutalizing forces of domination. Von Ebbrenac knows that he had been in denial, that his role as a German officer makes him a complicit element in an evil institution.

When von Ebbrenac returns to the couple's house, he tells them that he is leaving to return to the war. He has asked to be sent to "hell": the Russian front.

The Silence of the Sea is Melville's cinematic commentary on the nature of resistance to evil, although it does not feature any reference to the French Resistance. Both the German officer and the French uncle and niece offer, not physical, but moral resistance. He never ceases his lonely struggle to communicate his idealized vision of a better world, despite his efforts being (apparently) ignored. At the end he offers a sort of sacrifice by volunteering to go to what will probably be his death on the Russian front. The French couple in turn rely on moral willpower to overcome the fact that the occupier is a gentle, benign person. Only when he ceases to be an occupier can communication occur. The old man and the young woman resist the easy way out: communicating with the officer because he is a good person. The fact that he is part of an evil institution justifies their silence. The couple's attitude is in contrast with that of most French people during the Occupation - they were prepared to tolerate the German presence. By the film's end von Ebbrenac has finally realized why the pair refuse to talk to him - although a morally good individual, he is complicit in the terrible work of evil forces.

Jean-Pierre Melville's directorial style in The Silence of the Sea

Melville at work.

Silence of the Sea was Melville's first feature film, made in 1948. During the next 22 years he made another twelve movies. Born Jean-Pierre Grumach to Jewish parents in 1917, and a cinema fanatic from childhood, he loved American movies and American culture. During his mid-twenties Grumach changed his surname to Melville, after the author of Moby Dick. But the films he idolized belonged to commercial genres and studios that most intellectuals disdained during the period from the 1930s to the early fifties. Thus the gritty Warner Bros movies of the 1930s and thriller / gangster movies, along with stars like Bogart were lauded by Melville. During the second world war the aspiring director was a member of the Resistance. His later cinematic obsession with investigating loyalty and adherence to a personal code of honor and integrity may well have arisen of his experiences in the Resistance as well as the fact that these values are also central to many of the gangster/ thriller movies that he admired. LIke so many of the heroes in his films, Melville delighted in being on the outside, rejecting the mainstream. He was proudly right-wing at a time when most of his fellow intellectuals were left-wing; he praised American culture for years when it was anathema to French bien-pensants. He was secretive, caustic, ungrateful, impossible to please, proudly describing himself as "a solitary."

Throughout his career Melville made a virtue out of the very limited financial and technical resources that he had when he started The Silence of the Sea in 1948. He assisted with photography, costumes, script and set design. His credo of minimal production values, which included as much shooting on location as possible to avoid studio and union costs, were eventually copied by the young directors of the 'New Wave', like Godard and Truffaut. Through the movies of Melville this new generation of French directors were introduced to the riches provided by critically-despised Hollywood genres and directors. Using Melville as their mentor,they went on to appropriate motifs, themes and stylistic devices from this pool.

Throughout his career Melville made a virtue out of the very limited financial and technical resources that he had when he started The Silence of the Sea in 1948. He assisted with photography, costumes, script and set design. His credo of minimal production values, which included as much shooting on location as possible to avoid studio and union costs, were eventually copied by the young directors of the 'New Wave', like Godard and Truffaut. Through the movies of Melville this new generation of French directors were introduced to the riches provided by critically-despised Hollywood genres and directors. Using Melville as their mentor,they went on to appropriate motifs, themes and stylistic devices from this pool.

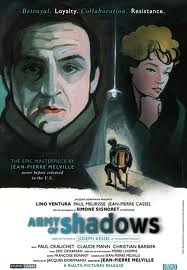

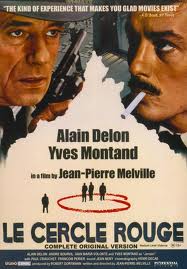

These stills from Silence of the Sea provide some insight into Melville's early style. The movie is the equivalent of chamber music, quiet and restrained. It has an unrelenting focus on figures seated or talking (or not talking at all), and key scenes are often shot in close-ups of faces. Shadows and contrasts abound. Ingmar Bergman borrowed heavily from this feature of Melville's technique. Melville's essential theme in all his movies is that of the necessity of loyalty and the need to maintain one's personal honor at all costs, and many of his shots in Silence close in on individuals in the process of making decisions that carry moral weight and personal consequences. These images and this theme are to be found in all his films, especially his superb movie on the Resistance, Army of Shadows (L'armée des ombre). His various thriller / underworld movies, such as Le Cercle Rouge combine variants on tough-guy edginess, exciting action sequences and sombre evocations of a dangerous underworld.

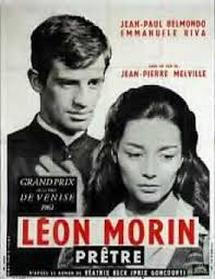

Melville went on to make two other films about occupation and resistance. His next was 1961's Léon Morin, Priest in which war, occupation and resistance are treated in an understated, indirect manner, but constituting essential background for his drama of temptation and faith. Almost two decades later came his masterpiece, Army of Shadows, a majestic and acerbic examination of the Resistance movement and the nature of betrayal.