Vietnam westerns: the western in the era of the Vietnam war

'The Western plot offers the perfect filter through which to look at the Vietnam war' - L. Furhammer & F. Isaksson

Western movies, although no longer a staple American film genre, have always had the potential to reflect or articulate the social and cultural values of their era. 'THe Western,' Philip French observed, ' is a great grab-bag, a hungry cuckoo of a genre, a vivacious bastard of a for ... ready to seize anything that's in the air....' So during the 1950s and early 1960s, as J.Fred MacDonald has noted, the western mirrored popular concerns of the Cold war era, with the Russians as global outlaws, intent on expansion and plunder, and the Americans as the heroic defenders of law and order and the decent peace-loving citizenry. John Wayne became the cinematic emblem of the 'good guys' in the struggle. he asumed many guises: Cavalry officer, sheriff, rancher, cattleman. But he was also laconic, no-nonsense, individualistic, stoic, protector of widows and orphans, with a heart of gold concealed beneath a rugged exterior.

Throughout the 1930s to the late 1950s Indians were frequently portrayed as ruthless predators, "'the red menace, a dangerous threat to White Civilization"' [Eugene Levy], the embodiment of anarchy, savagery and destruction. Their attributes included stealth, cunning and ruthlessness. However, some movies of that era used a rather different, if demeaning and paternalistic stereotype of Indians. The 'good' Indians were shown as naive, almost childlike, friendly , a bit stupid and occasionally courageous. They are often treated as buffoons and provide comic relief.

This duality is illustrated in John Ford's 1930 movie Drums Along the Mohawk, which has the interesting setting of pre-revolutionary era Mohawk Valley in upstate New York - then a region which marked part of what was the Indian frontier in that era. The 'bad' Indians -cruel and cunning - are fighting on the side of the devious British who are encouraging them to attack the American settlers, the 'good' Indians - amiable, harmless, gullible and simple - are aligned with the settlers. The settlers treat them as children and take it for granted that they will be grateful for the blessings of white civilization. 'I don't think we'll have any trouble with the Indians. We've always treated them fair' asserts the film's hero (Henry Fonda).

Below: creatures of nightmare - the movie's 'bad' Indians; the epitome of savagery

Throughout the 1930s to the late 1950s Indians were frequently portrayed as ruthless predators, "'the red menace, a dangerous threat to White Civilization"' [Eugene Levy], the embodiment of anarchy, savagery and destruction. Their attributes included stealth, cunning and ruthlessness. However, some movies of that era used a rather different, if demeaning and paternalistic stereotype of Indians. The 'good' Indians were shown as naive, almost childlike, friendly , a bit stupid and occasionally courageous. They are often treated as buffoons and provide comic relief.

This duality is illustrated in John Ford's 1930 movie Drums Along the Mohawk, which has the interesting setting of pre-revolutionary era Mohawk Valley in upstate New York - then a region which marked part of what was the Indian frontier in that era. The 'bad' Indians -cruel and cunning - are fighting on the side of the devious British who are encouraging them to attack the American settlers, the 'good' Indians - amiable, harmless, gullible and simple - are aligned with the settlers. The settlers treat them as children and take it for granted that they will be grateful for the blessings of white civilization. 'I don't think we'll have any trouble with the Indians. We've always treated them fair' asserts the film's hero (Henry Fonda).

Below: creatures of nightmare - the movie's 'bad' Indians; the epitome of savagery

Chief Big Tree as the good Indian Blue Black in Drums Along the Mohawk: friendly, childlike, a bit foolish, sometimes dignified.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s the Vietnam conflict was at its height. So was the controversy within America over that country's involvement in the war. The Western genre was adapted in order to comment on the war and the military. Not all attempts succeeded. John Wayne's second directorial effort, The Green Berets, uneasily combined features of the cavalry movie and his World War II action films to endorse US participation in the war. Here the American forces were brave warriors coming to the aid of the South Vietnamese. Ralph Nelson's Soldier Blue reversed this benign image. Its clumsy and sensationalist compilation of scenes of rape and atrocities portrayed the American military as vicious, cowardly and unscrupulous .

But three fine directors - Sam Peckinpah, Arthur Penn and Robert Aldrich - made three outstanding movies which demythologised many aspects of the traditional Western movie, as well as commenting on the Vietnam conflict.

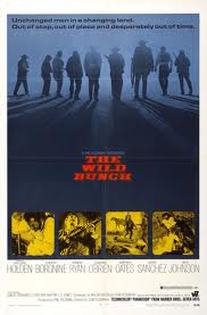

Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969) is largely set in Mexico in 1913, during a period of civil war. The outlaws after whom the movie gets its name become involved in this conflict, so synbolising American involvement in foreign countries. The outlaws' fate seems to be a warning of the outcome of such participation in foreign conflicts.

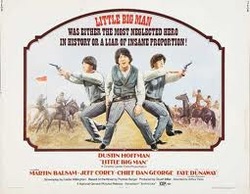

Little Big Man (1970) is Arthur Penn's ambitious, epic take on the entire western genre, with the U.S. military campaign of exterminating Indians standing in for the contemporary American treatment of Vietamese. The movie rather naively reverses the customary 'bad Indians -good whites' stereotype. here the Cheyenne are noble, courageous, defenders of their lifestyle against the greed, violence and maliciousness of white settlers and military.

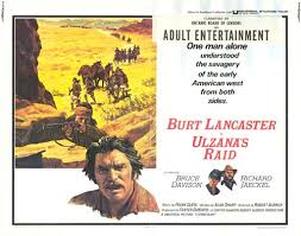

Robert Aldrich's little-known Ulzana's Raid (1972) is rather more realistic. Set in late 19th Century Arizona, the film is about another guerrilla war -this time on American soil, not South-East Asia. The guerillas are a tribe of Apache who are raiding white settlements. They are pursued by a U.S. cavalry unit led by a naive and gullible officer, reluctantly helped by a cynical and experienced Indian scout. Ulzana's Raid captures perfectly the dilemma the American military faced in Vietnam: they are fighting ruthless and dedicated opponents operating at will in their own territory and moving with a speed and stealth the Americans cannot match. The cavalry's superior firepower is outclassed by their enemy's knowledge of the terrain and their willingness to viciously exploit the suffering of the civilians they target and use as traps to lure the soldiers into danger.

But three fine directors - Sam Peckinpah, Arthur Penn and Robert Aldrich - made three outstanding movies which demythologised many aspects of the traditional Western movie, as well as commenting on the Vietnam conflict.

Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969) is largely set in Mexico in 1913, during a period of civil war. The outlaws after whom the movie gets its name become involved in this conflict, so synbolising American involvement in foreign countries. The outlaws' fate seems to be a warning of the outcome of such participation in foreign conflicts.

Little Big Man (1970) is Arthur Penn's ambitious, epic take on the entire western genre, with the U.S. military campaign of exterminating Indians standing in for the contemporary American treatment of Vietamese. The movie rather naively reverses the customary 'bad Indians -good whites' stereotype. here the Cheyenne are noble, courageous, defenders of their lifestyle against the greed, violence and maliciousness of white settlers and military.

Robert Aldrich's little-known Ulzana's Raid (1972) is rather more realistic. Set in late 19th Century Arizona, the film is about another guerrilla war -this time on American soil, not South-East Asia. The guerillas are a tribe of Apache who are raiding white settlements. They are pursued by a U.S. cavalry unit led by a naive and gullible officer, reluctantly helped by a cynical and experienced Indian scout. Ulzana's Raid captures perfectly the dilemma the American military faced in Vietnam: they are fighting ruthless and dedicated opponents operating at will in their own territory and moving with a speed and stealth the Americans cannot match. The cavalry's superior firepower is outclassed by their enemy's knowledge of the terrain and their willingness to viciously exploit the suffering of the civilians they target and use as traps to lure the soldiers into danger.

Western elements in a Vietnam movie: Apocalypse Now

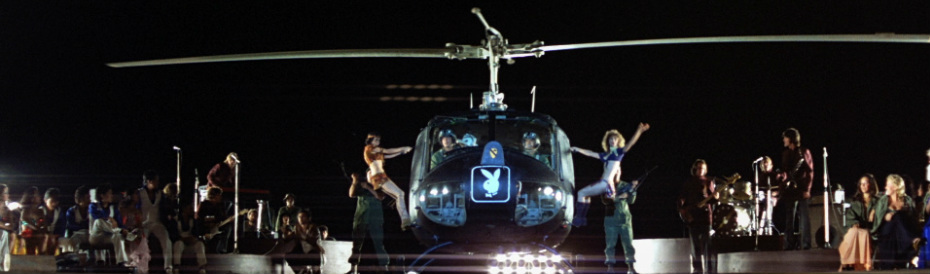

One scene in Coppola's masterpiece on Vietnam involves a clever reference to the Western genre. This occurs when Willard and his crew emerge from the darkness in their boat to find a brightly stadium by the side of the river. The avidly waiting soldiers are about to see a UFO troupe of Playboy bunnies, delivered by military helicopter put on a performance. Two of the girls are (un)dressed as a be-holstered cowgirl and an Indian maiden respectively. Their dance routine stimulates the soldiers to the point where they rush the stage and the troupe has to be abruptly helicoptered out. Meanwhile crowds of Vietnamese civilians eat their rice and placidly watch. It's a marvellous sequence - funny, sexy and ironic. Instead of the traditional Western stereotype of the cavalry bringing supplies to troops in a fort in hostile Indian territory, we have the modern air cavalry bringing Playboy bunnies referencing cowboy movies to soldiers who aren't exactly the stoic, self-possessed figures of Western mythology.

One scene in Coppola's masterpiece on Vietnam involves a clever reference to the Western genre. This occurs when Willard and his crew emerge from the darkness in their boat to find a brightly stadium by the side of the river. The avidly waiting soldiers are about to see a UFO troupe of Playboy bunnies, delivered by military helicopter put on a performance. Two of the girls are (un)dressed as a be-holstered cowgirl and an Indian maiden respectively. Their dance routine stimulates the soldiers to the point where they rush the stage and the troupe has to be abruptly helicoptered out. Meanwhile crowds of Vietnamese civilians eat their rice and placidly watch. It's a marvellous sequence - funny, sexy and ironic. Instead of the traditional Western stereotype of the cavalry bringing supplies to troops in a fort in hostile Indian territory, we have the modern air cavalry bringing Playboy bunnies referencing cowboy movies to soldiers who aren't exactly the stoic, self-possessed figures of Western mythology.