Farewell, My Queen (2012) Dir: Benoit Jacquot

Les adieux a la reine

A Refreshingly New Perspective on Marie Antoinette & the Versailles Court

oThe artist Elizabeth Louise Vigee Le Brun who painted this controversial 1783 portrait of the Queen (on left) observed noted that her restlessness made her a difficult subject to portray. Vigee became the Queen's official artist. This portrait was regarded as scandalous by the French public, who were shocked by the (comparatively) simple white English-fashion Muslin dress, the informal straw hat and complete lack of ornaments, and the smile (undignified!) The artist was forced to replace it with a version depicting the Queen in an elaborate French-style silk dress and an elaborate coiffure,shown on right.

[Anka Muhlstein, 'A Most Successful Woman',New York Review of Books, XLIII,No 5, 2016]

[Anka Muhlstein, 'A Most Successful Woman',New York Review of Books, XLIII,No 5, 2016]

Friend, Confidante, Mentor, (Lover?) - Duchesse Yolande Gabrielle de Polignac

The Popular Press, the Wicked Queen of Versailles and the Duchesse de Polignac

'La reine scélérate' .

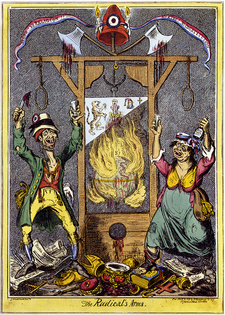

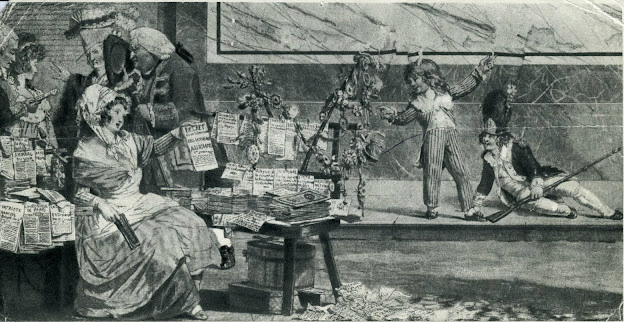

Farewell, My Queen deals subtly with one aspect of the monarchy that has become the subject of much scholarly discussion in recent years. This concerns the significance of the ways in which contemporary French publications, many of them pornographic, such as songs, cartoons, broadsheets, poems and popular art, - the tabloid press of the day - depicted the royal couple and their aristocratic hangers-on at Versailles. In 1986 Chantal Thomas published La reine scélélerate (The Wicked Queen) and argued that the Queen was undermined by the constant scurrilous depictions of her. Among other charges, she was accused of infidelity,espionage, bestiality, murder, incest, witchcraft, treason and lesbianism. Thomas's book examines a range of such depictions, and concludes that not only do they constitute a male horror of the female body; they also form a 'misogynist demonization' of the Queen and indeed of women's status and power in France. Such imagery, Thomas argues, was an attempt to replace a feminized, corrupt monarchy with a republic representing the 'male' virtues of honesty, dignity and justice.o

Unfortunately, Thomas fails to recognize that scandalous depictions were not confined to Marie Antoinette. Louis XVI was subjected to an equally vitriolic attack and his sexual and moral attributes were just as viciously attacked as were the Queen's. So too were the manners and morals of others at the Court, male as well as female. This aspect has been more recently discussed in a superior study, The Body Politic by Antoine Baecque. The author points out that French popular literature of the late 18th Century habitually used images of the body, both male and female, especially the bodies of the King , Queen, aristocrats and revolutionaries alike to both condemn and praise. Thus Louis was depicted as impotent and flaccid, Marie as bestial, and the aristocracy as monstrous. Images of women revolutionaries, far from denigrating either their bodies or their abilities, depicted them as heroic leaders, models for their menfolk to emulate.

Unfortunately, Thomas fails to recognize that scandalous depictions were not confined to Marie Antoinette. Louis XVI was subjected to an equally vitriolic attack and his sexual and moral attributes were just as viciously attacked as were the Queen's. So too were the manners and morals of others at the Court, male as well as female. This aspect has been more recently discussed in a superior study, The Body Politic by Antoine Baecque. The author points out that French popular literature of the late 18th Century habitually used images of the body, both male and female, especially the bodies of the King , Queen, aristocrats and revolutionaries alike to both condemn and praise. Thus Louis was depicted as impotent and flaccid, Marie as bestial, and the aristocracy as monstrous. Images of women revolutionaries, far from denigrating either their bodies or their abilities, depicted them as heroic leaders, models for their menfolk to emulate.

Jacquot's movie refers to one of the lesser charges against the Queen, that of lesbianism, especially in relationship to her friend and confidante, the Duchesse de Polignac.The Duchesse de Polignac is as controversial a figure as Marie Antoinette herself. Indeed, controversy seems to have followed her descendants -her great-great-great-great grandchildren are the Princesses Caroline, Stephanie and Prince Albert of Monaco. She was born in 1749, and was thus six years older than Marie Antoinette. Like the future Queen, had an arranged marriage (at age 17) to Count Jules Polignac, who came from a proudly aristocratic but financially embarrassed family which had for centuries clung close to royal power and influence.

There are two divergent views of the duchesse. The dominant view, largely supported by historical evidence, is that Gabrielle assidiously worked to obtain favours, wealth and influence for herself and the Polignac family. She first met Marie in 1775 and immediately the two became close friends. Gabrielle insisted, however, that she would not move into the court unless her husband was given a lucrative post and the family debts were paid. She used her shrewdness to inveigle her way into the affections of not only Marie Antoinette, but KIng Louis and his young brother. These invaluable connexions produced an outpouring of royal patronage on a scale that astounded and infuriated other courtiers, jealous of the privileges bestowed on the Polignacs. Louis actively encouraged the friendship between the older, more assured woman and his often lonely, easily distracted wife: he believed that Gabrielle had a calming influence on the Queen. The younger Marie appears to have relied on the ambitious older woman and mother of four for advice on matters social, sexual and gynaecological.Polignac certainly used her friendship to accumulate favours and privileges to an extent unequalled by any other royal favourite in Louis' court. In 1782 she was given the prestigious title of Governess to the Children of France (i.e. to the royal children) and a thirteen-room apartment in the palace, as well as her own 'cottage' near the Queen's beloved Hameau de la Reine, a faux Disneyfied rural homestead.

The most serious charges against Polignac's influence on the Queen are political. She encouraged Marie to become encapsulated within a lifetsyle completely detached from the social and political realities of late eighteenth century France. Under her guidance the Queen not only became a symbol of frivolity, laziness and excess, completely divorced from the needs of the enormous majority of her subjects. She also became the easy target for slander and gossip, thereby combining allegations of immorality with profligacy. The Duchesse's political stance also had unfortunate repercussions for Marie. In 1789 Gabrielle had become what would now be called a 'hard-liner'. She, along with the King's brother the Comet d'Artois, demanded a forceful response to the growing political and social discontent in Paris and the rest of France. Gabrielle, along with Artois and others successfully pushed the King to dismiss his chief minister Jacques Necker, one of the few who realised both the seriousness of the discontent and the monarchy's inability to crush it by armed force. Necker's sacking triggered armed insurrection in Paris.

Defenders of Gabrielle correctly note that nepotism and corruption were hardly unique to the Polignacs; the entire court at Versailles was completely contaminated by it. Gabrielle was only doing what dozens of her rivals were doing, only more successfully. Besides, Gabrielle did not dominate the Queen's affections; Marie had another powerful favourite, the Princesse de Lamballe. They also point out the jealousy that motivated other courtiers' hatred of the Duchesse. The allegations that Gabrielle was committing acts of gross immorality remain unsubstantiated - although she and the Comte de Vaudreille may well have been lovers. Again, such conduct was hardly unique at the court. Her defenders claim that the Duchesse was essentially a beautiful, witty, brave figure, caring and kind-hearted, who loved her children and protected the Queen.

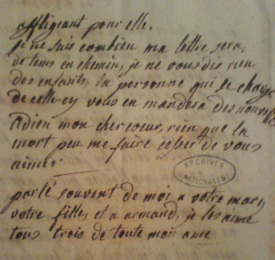

However, Gabrielle's behaviour when things turned bad tends to confirm the negative view of her as opportunistic. As early as 14 July she and her family fled Versailles and ended up in the safe haven of Switzerland. From there she carried on a correspondence with the Queen, an exchange which shows that Marie was still devoted to her. She had been unwell for some time and her condition worsened until she she died in 1793, a few days after the Queen's execution. Her supporters then and now claim she died of a broken heart, and her epitaph claims that "she died of sorrow". A more mundane explanation is that she died of either cancer or tuberculosis.

There are two divergent views of the duchesse. The dominant view, largely supported by historical evidence, is that Gabrielle assidiously worked to obtain favours, wealth and influence for herself and the Polignac family. She first met Marie in 1775 and immediately the two became close friends. Gabrielle insisted, however, that she would not move into the court unless her husband was given a lucrative post and the family debts were paid. She used her shrewdness to inveigle her way into the affections of not only Marie Antoinette, but KIng Louis and his young brother. These invaluable connexions produced an outpouring of royal patronage on a scale that astounded and infuriated other courtiers, jealous of the privileges bestowed on the Polignacs. Louis actively encouraged the friendship between the older, more assured woman and his often lonely, easily distracted wife: he believed that Gabrielle had a calming influence on the Queen. The younger Marie appears to have relied on the ambitious older woman and mother of four for advice on matters social, sexual and gynaecological.Polignac certainly used her friendship to accumulate favours and privileges to an extent unequalled by any other royal favourite in Louis' court. In 1782 she was given the prestigious title of Governess to the Children of France (i.e. to the royal children) and a thirteen-room apartment in the palace, as well as her own 'cottage' near the Queen's beloved Hameau de la Reine, a faux Disneyfied rural homestead.

The most serious charges against Polignac's influence on the Queen are political. She encouraged Marie to become encapsulated within a lifetsyle completely detached from the social and political realities of late eighteenth century France. Under her guidance the Queen not only became a symbol of frivolity, laziness and excess, completely divorced from the needs of the enormous majority of her subjects. She also became the easy target for slander and gossip, thereby combining allegations of immorality with profligacy. The Duchesse's political stance also had unfortunate repercussions for Marie. In 1789 Gabrielle had become what would now be called a 'hard-liner'. She, along with the King's brother the Comet d'Artois, demanded a forceful response to the growing political and social discontent in Paris and the rest of France. Gabrielle, along with Artois and others successfully pushed the King to dismiss his chief minister Jacques Necker, one of the few who realised both the seriousness of the discontent and the monarchy's inability to crush it by armed force. Necker's sacking triggered armed insurrection in Paris.

Defenders of Gabrielle correctly note that nepotism and corruption were hardly unique to the Polignacs; the entire court at Versailles was completely contaminated by it. Gabrielle was only doing what dozens of her rivals were doing, only more successfully. Besides, Gabrielle did not dominate the Queen's affections; Marie had another powerful favourite, the Princesse de Lamballe. They also point out the jealousy that motivated other courtiers' hatred of the Duchesse. The allegations that Gabrielle was committing acts of gross immorality remain unsubstantiated - although she and the Comte de Vaudreille may well have been lovers. Again, such conduct was hardly unique at the court. Her defenders claim that the Duchesse was essentially a beautiful, witty, brave figure, caring and kind-hearted, who loved her children and protected the Queen.

However, Gabrielle's behaviour when things turned bad tends to confirm the negative view of her as opportunistic. As early as 14 July she and her family fled Versailles and ended up in the safe haven of Switzerland. From there she carried on a correspondence with the Queen, an exchange which shows that Marie was still devoted to her. She had been unwell for some time and her condition worsened until she she died in 1793, a few days after the Queen's execution. Her supporters then and now claim she died of a broken heart, and her epitaph claims that "she died of sorrow". A more mundane explanation is that she died of either cancer or tuberculosis.

|

|

|