1941

The frenetic poster for Steven Spielberg's comedy 1941 was a perfect reflection of the movie: brash, frenetic, chaotic and garish. At the time of the film's release in 1979, Spielberg was coming off the astonishing critical and commercial successes of Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Critics were waiting to pounce on the young cinematic genius and 1941 gave them the perfect opportunity. The movie was slammed as tasteless, racist, sexist, childish, incoherent and confused. Spielberg himself once claimed that "I will spend the rest of my life disowning this movie'". Yet 1941 has gradually acquired cult status, and its vibrancy and enthusiasm, and its sustained and ingenious comic sequences have become admired.1941 is now seen as belonging to that critically-disdained movie genre of mad-cap, anarchic comedy such as Hellzapoppin! and It''s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

The key incidents that make up 1941 - a Japanese submarine attack, an apparent bombing raid on the city, a riot on city streets, panic within Los Angeles - although apparently the result of the over-fevered imaginations of the scriptwriters Robert Gale and Robert Zemickis, actually did have a basis in historical fact, although the movie conflates several separate events into less than twenty-four hours on 13 December, 1941.

The key incidents that make up 1941 - a Japanese submarine attack, an apparent bombing raid on the city, a riot on city streets, panic within Los Angeles - although apparently the result of the over-fevered imaginations of the scriptwriters Robert Gale and Robert Zemickis, actually did have a basis in historical fact, although the movie conflates several separate events into less than twenty-four hours on 13 December, 1941.

The Historical Events Behind the Comedy of 1941

Three separate events provide the basis of Spielberg's movie:

(1) the shelling of the Ellwood oil refinery near Santa Barbara by a Japanese submarine on 23 February, 1942

(2) The battle of Los Angeles a.k.a. the Great Los Angeles Air Raid of the night of 24-25 February, 1942

(3) The Zoot Suit riots between white armed force personnel and Latino youths in Los Angeles, May-June 1943

1. Japanese submarine I-17 makes the first Axis attack on the US mainland, 23 February, 1942

After the attack on Pearl Harbor , submarine I-17, with its 101 officers and crew, along with six other Japanese submarines sank several merchant vessels off America's west coast. It sank a tanker off Cape Mendocino and resupplied at Kwajalewin. In the New Year, under the command of Kozo Nishino, it returned to west coast area. Before the war Nishino had been a tanker captain carrying oil from Ellwood to Japan.On the early evening of 23 February, I-17 was in the Santa Barbara channel, from where it shelled several oil tanks onshore for twenty minutes. Little damage was caused, and some shells landed on a nearby ranch and the Ellwood pier. The I-17 eventually returned to Japan. although throughout the rest of the war Japanese submarines continued to harass merchant shipping off the North American west coast. At least one launched incendiary balloons intended to start fires in the forests of Oregon.

1941 uses the events of 23 February as a rather clumsy sequence that kick-starts the plot. Most of what the movie shows is entirely fictitious. However, 1941 is correct in showing that the I-17's shelling created panic and hysteria in Los Angeles and revealed ineptitude on the part of the local military and civic authorities in the face of the first Axis attack on the mainland USA. The next night saw the infamous 'Battle of Los Angeles', where the panic and incompetence escalated.

The Fate of I-17 In August 1943, 97 of the submarine's complement of 103 were killed when it sank in the southwest Pacific after being attacked by the New Zealand navy anti-submarine trawler HMNZS Tui and several American aircraft.

1941 uses the events of 23 February as a rather clumsy sequence that kick-starts the plot. Most of what the movie shows is entirely fictitious. However, 1941 is correct in showing that the I-17's shelling created panic and hysteria in Los Angeles and revealed ineptitude on the part of the local military and civic authorities in the face of the first Axis attack on the mainland USA. The next night saw the infamous 'Battle of Los Angeles', where the panic and incompetence escalated.

The Fate of I-17 In August 1943, 97 of the submarine's complement of 103 were killed when it sank in the southwest Pacific after being attacked by the New Zealand navy anti-submarine trawler HMNZS Tui and several American aircraft.

2. The 'Battle' of Los Angeles / Great Los Angeles Air Raid, 24-25 February, 1942

A day after the Ellwood shelling, there occurred a series of farcical events that provide the basis for several crucial sequences in 1941. Hysteria - politely called "war nerves" by a 1963 inquiry - over the shelling quickly escalated the next evening to rumors about a Japanese air attack on the city and a resulting anti-aircraft attack on supposed targets in the night sky. The decision to alert air-raid wardens and impose a total blackout over the city, as well as shut down many of southern California's radio stations exacerbated the military and public over-reaction. The news commentary broadcast below reveals the confusion and uncertainty. Its references to "objects" in the night sky later provided UFO believers with "evidence" of a alien presence above L.A. However, the 1983 study by the US Office of War History blames the more mundane presence of a stray weather balloon being fired on by excited anti-aircraft battery operators. This friendly fire may have killed three three civilians; three more may have died from heart attacks.

Inquiries into the fiasco began immediately. Various scenarios were provided, almost all lacking any evidentiary proof whatsoever. These included claims that Mexico was providing Japan with secret airbases to attack the US. Another claimed that the US government was to blame for it wanted an excuse to move defense industries away from California. The Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox blamed "war nerves" and anxiety - a reasonable assessment - but his views were widely regarded as part of an elaborate cover-up.

The movie does a good job of showing these "war nerves'. However, the flights of P-17 fighters, and depictions of damage are fictional. There were riots in 1943, but they were racist in origin, rather than arising from inter-service rivalry as shown in the movie.

Inquiries into the fiasco began immediately. Various scenarios were provided, almost all lacking any evidentiary proof whatsoever. These included claims that Mexico was providing Japan with secret airbases to attack the US. Another claimed that the US government was to blame for it wanted an excuse to move defense industries away from California. The Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox blamed "war nerves" and anxiety - a reasonable assessment - but his views were widely regarded as part of an elaborate cover-up.

The movie does a good job of showing these "war nerves'. However, the flights of P-17 fighters, and depictions of damage are fictional. There were riots in 1943, but they were racist in origin, rather than arising from inter-service rivalry as shown in the movie.

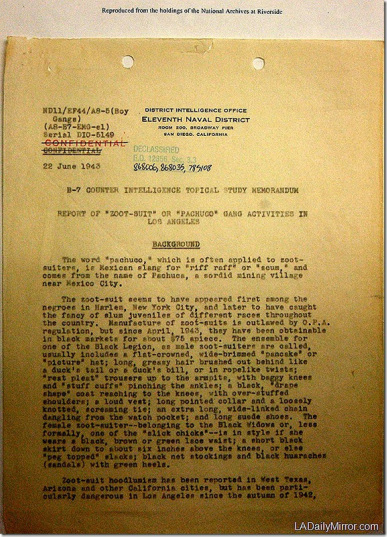

3. The LA Zoot-Suit Riots of mid-1943

Photo above from L/A. Times shows a crowd stopping a streetcar on Main Street, LA in search of Zoot Suiters,

8 June, 1943. Note the emotive claim below the photo: "The rebellion was caused by zoot gangs molesting citizens."

The scenes of riotous mayhem in Los Angeles that make up a large part of 1941 are based on the so-called "Zoot Suit riots" that actually occurred in early June, 1943. Unfortunately, the riots were hardly noted for their comic exuberance. In fact, after more than half a century they constitute a serious blot on the American military,the local press, civic authorities and the LA police department. All these aspects are ignored by 1941, although to be fair to the movie it is concerned openly with transplanting scenes of civic and intra-military disturbances onto a fictional scenario. Some scenes of rioting in 1941 show a few Zoot suiters, but the film shows the mayhem as essentially extended brawls between sailors, marines and soldiers.

The 1943 riots were named after an interesting fashion phenomenon of the early 1940s, which according to Kathy Peis originated amongst African-Americans in Harlem during the 1930s. The name itself may derive from African-American rhyming slang. The style featured a large jacket with very long sleeves, pants cinched at the waist, swollen at knee level and tight at the ankles, thick soled shoes. Other features included a long key chain and a fedora that often had a feather attached.

This flamboyant and highly conspicuous costume and the values it represented became the trigger for communal violence in LA. Its catalyst was the simmering racial tension between the city's Mexican-American population, especially its young men, and white servicemen stationed in southern California. Mexican-Americans faced job and wage discrimination, and were victimized by police and newspapers. The zoot suit worn by some Mexican-American males became the outward manifestation of a distinctive sub-culture. It was also associated with gangs' criminal activities. Many whites objected to the style because they regarded it as unpatriotic. The zoot suit ignored the official clothing regulations guidelines on the rationing of fabrics as a war economy measure. Its voluminous design, and use of woolen fabric stood in stark contrast to the simpler, cheaper, plain military uniforms. It was also blatantly not designed for warfare. Thus it was easy to accuse its wearers specifically, and Mexican-Americans collectively, of a lack of patriotism in the midst of war.

Accordingly, the riots of 1943 combined racial discrimination, wartime nerves, sensationalist reporting, poverty and testosterone-driven group violence. Fights between servicemen and Zoot suiters in late May escalated to all-out confrontation starting on 3 June, with off-duty police playing an inciting role. Soon thousands of sailors, marines and soldiers were roaming the streets looking for Zoot suiters. They marched into bars, movie theaters and pulled people off trolleys and buses. Most of their victims were young teens. Many Mexican-Americans and some Filipinos and African-Americans were physically assaulted with clubs and and forced to remove their suits. Such tactics continued for several days with organized groups of military police and Navy Shore Patrols searching for soot-suited "gangsters" and "de-zooting" them. It took until On 7 June before military authorities intervened. Troops and sailors were confined rot barracks and banned from entering Los Angles.

Although these authorities maintained that their personnel had been acted in self-defense, an official inquiry established by California's Governor soon found that racism was the fundamental cause of the riot, and that the press had exacerbated the situation.

8 June, 1943. Note the emotive claim below the photo: "The rebellion was caused by zoot gangs molesting citizens."

The scenes of riotous mayhem in Los Angeles that make up a large part of 1941 are based on the so-called "Zoot Suit riots" that actually occurred in early June, 1943. Unfortunately, the riots were hardly noted for their comic exuberance. In fact, after more than half a century they constitute a serious blot on the American military,the local press, civic authorities and the LA police department. All these aspects are ignored by 1941, although to be fair to the movie it is concerned openly with transplanting scenes of civic and intra-military disturbances onto a fictional scenario. Some scenes of rioting in 1941 show a few Zoot suiters, but the film shows the mayhem as essentially extended brawls between sailors, marines and soldiers.

The 1943 riots were named after an interesting fashion phenomenon of the early 1940s, which according to Kathy Peis originated amongst African-Americans in Harlem during the 1930s. The name itself may derive from African-American rhyming slang. The style featured a large jacket with very long sleeves, pants cinched at the waist, swollen at knee level and tight at the ankles, thick soled shoes. Other features included a long key chain and a fedora that often had a feather attached.

This flamboyant and highly conspicuous costume and the values it represented became the trigger for communal violence in LA. Its catalyst was the simmering racial tension between the city's Mexican-American population, especially its young men, and white servicemen stationed in southern California. Mexican-Americans faced job and wage discrimination, and were victimized by police and newspapers. The zoot suit worn by some Mexican-American males became the outward manifestation of a distinctive sub-culture. It was also associated with gangs' criminal activities. Many whites objected to the style because they regarded it as unpatriotic. The zoot suit ignored the official clothing regulations guidelines on the rationing of fabrics as a war economy measure. Its voluminous design, and use of woolen fabric stood in stark contrast to the simpler, cheaper, plain military uniforms. It was also blatantly not designed for warfare. Thus it was easy to accuse its wearers specifically, and Mexican-Americans collectively, of a lack of patriotism in the midst of war.

Accordingly, the riots of 1943 combined racial discrimination, wartime nerves, sensationalist reporting, poverty and testosterone-driven group violence. Fights between servicemen and Zoot suiters in late May escalated to all-out confrontation starting on 3 June, with off-duty police playing an inciting role. Soon thousands of sailors, marines and soldiers were roaming the streets looking for Zoot suiters. They marched into bars, movie theaters and pulled people off trolleys and buses. Most of their victims were young teens. Many Mexican-Americans and some Filipinos and African-Americans were physically assaulted with clubs and and forced to remove their suits. Such tactics continued for several days with organized groups of military police and Navy Shore Patrols searching for soot-suited "gangsters" and "de-zooting" them. It took until On 7 June before military authorities intervened. Troops and sailors were confined rot barracks and banned from entering Los Angles.

Although these authorities maintained that their personnel had been acted in self-defense, an official inquiry established by California's Governor soon found that racism was the fundamental cause of the riot, and that the press had exacerbated the situation.

|

|

Some Scenes in 1941 That Definitely Are Not Historical Fact

A Tragic Aftermath of the 'Invasion' Hysteria Depicted in 1941

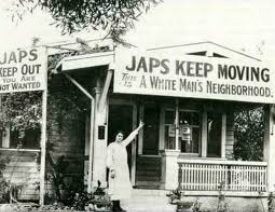

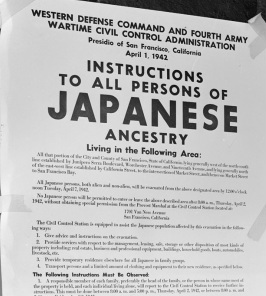

The hysteria produced by the Ellwood shelling and the subsequent 'Great Los Angeles Air Raid' in early 1942 fed into the public anger and fear that resulted from the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The west coast of the USA, especially California, had large pockets of people of Japanese origin - most of them being American citizens. However, the humiliation over the fiasco of early February only stimulated rumors about infiltration of spies and even military units amongst the region's Japanese-American population. This mood was in flamed by unscrupulous local and national politicians, and local farmers, unions and business groups eager to remove Japanese-American competitors for jobs and profits.

A few days after the panics of early February, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which allowed 'military areas' to be designated as 'exclusion zones' from which individuals or specific groups of people cloud be excluded.Under this Order all people of Japanese ancestry, including American citizens, were excluded from the Pacific coast area. They were eventually interned in 'War Re-Location Centers', many of which provided inadequate food, shelter, medical, plumbing and educational amenities. At least in the USA families were allowed to stay together. In Canada, people of Japanese origin were sent to similar camps but males were separated from women and and children and sent to labor camps.

Although the American Supreme Court twice ruled that the internment policy was constitutional, it is not recognized as a shameful occasion in American history and a blot on Roosevelt's reputation. In 1988 Congress and President Reagan apologized for the policy and its effects, describing it as the sad result of "race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership." Reparations of $1.6 billion paid to internees and descendants.

A few days after the panics of early February, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which allowed 'military areas' to be designated as 'exclusion zones' from which individuals or specific groups of people cloud be excluded.Under this Order all people of Japanese ancestry, including American citizens, were excluded from the Pacific coast area. They were eventually interned in 'War Re-Location Centers', many of which provided inadequate food, shelter, medical, plumbing and educational amenities. At least in the USA families were allowed to stay together. In Canada, people of Japanese origin were sent to similar camps but males were separated from women and and children and sent to labor camps.

Although the American Supreme Court twice ruled that the internment policy was constitutional, it is not recognized as a shameful occasion in American history and a blot on Roosevelt's reputation. In 1988 Congress and President Reagan apologized for the policy and its effects, describing it as the sad result of "race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership." Reparations of $1.6 billion paid to internees and descendants.