Generation War - Swing Kids

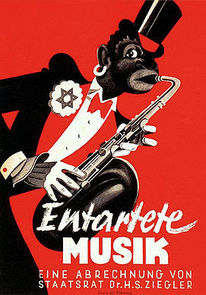

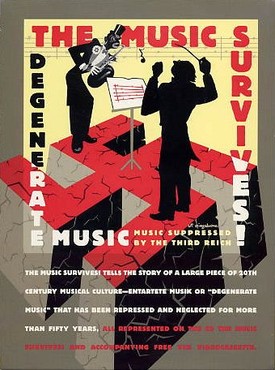

A sequence at the start of Generation War accurately depicts the official Nazi response to the jazz music that the series' five protagonists are enjoying. They are warned by an SS officer that listening to it is unlawful and unGerman. For the Third Reich, jazz and its variants were 'Entarte Musuk' - Degenerate Music, a cultural blasphemy. The Nazis regarded jazz as the inferior product of what they regarded as 'inferior' races, namely negroes and Jews. . Other. less obvious aspects of jazz also aroused the displeasure not only of the Nazis but of some Germans who otherwise regarded Hitler and his followers as dangerous oafs. They disliked the spontaneity and informality of jazz music and dance, its lack of academic respectability, its sometimes vulgar lyrics and its disdain for accepted musical conventions. IT was individualistic, not collective. Apart from the racial aspect emphasised by the Nazis, the case against Jazz was essentially that it was the antithesis of the high culture beloved by the high bourgeoisie of Europe, Britain and America. Worse still - jazz's performers and enthusiasts delighted in that very fact.

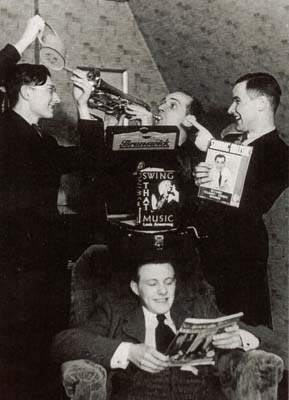

One of the very few movies about jazz, swing music and the Nazis is the 1993 Hollywood film, Swing Kids, with Christian Slater in his first starring role. Although unsuccessful at the time, it does a remarkabkle job of conveying the exhiliration and appeal of swing to young Germans. It also explores, much more deeply than Generation War, the impact of Nazi ideology on friendship and family, as well as on culture.

One of the very few movies about jazz, swing music and the Nazis is the 1993 Hollywood film, Swing Kids, with Christian Slater in his first starring role. Although unsuccessful at the time, it does a remarkabkle job of conveying the exhiliration and appeal of swing to young Germans. It also explores, much more deeply than Generation War, the impact of Nazi ideology on friendship and family, as well as on culture.

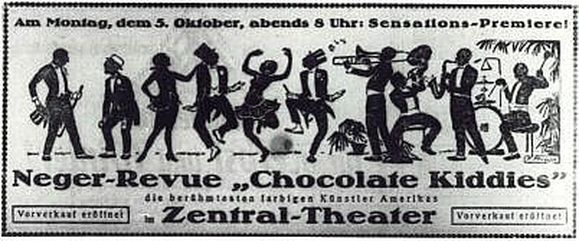

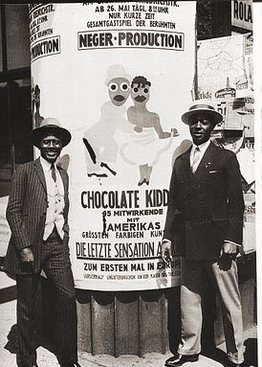

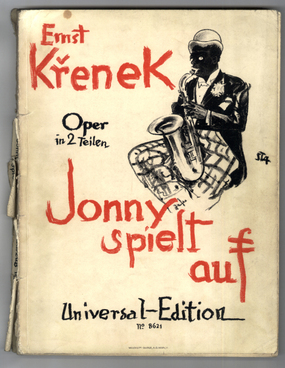

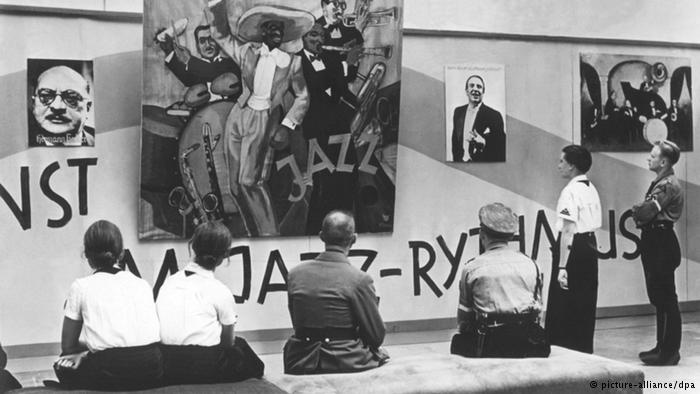

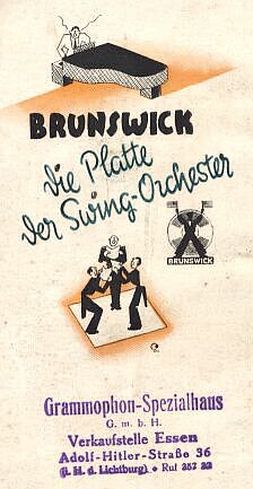

Examples of music labelled as degenerate and 'un German, ranging from jazz to composers of Jewish origin or left-wing sympathies, are obtainable on disk [above, middle]. Operetta wasalso condemned, as was atonal music. Alban Berg, Paul Hindemith and Igor Stravinsky were among classical composers whose work was classified as 'cultural bolshevism.' During the twenties some musical productions basaed on jazz performances of Negro musicians were popular in Berlin and some other German cities. One of the these productions was Chocolate Kiddies (note the name of the prduction company on poster top and above left). Another popular item in the late twenties was a jazz 'opera' Jonny strikes up [the band], by a Czech-Austrian composer Ernst Kronek, a fan of the jazz bands touring Germany after the war. The picture of the negro musician with saxophone in poster above was used as a model for the brochure of the 1938-9 exhibition. Incidentally, the saxophone was regarded with great suspicion by the Nazis. For them it represented black-Jewish-American culture at its worst. Jonny strikes up was singled out for special mention in the brochure. It declared that "A people that nears hysteria in its praise for 'Jonny,' who has already shown off much too long for that people, has grown spiritually and mentally ill, and is internally confused and unclean."

[above images from http://leroidesbelges.wordpress.com and http://www.return2style.de]

Under the Third Reich, action against jazz bands and their fans was uncoordinated and ambiguous. Municipal authorities, police, Nazi party functionaries and the SS initially tried to stamp out the music but the 1936 Berlin Ol;ympics meant that repressive policies were temporarily relaxed.and then tightened again after 1938 under the leadership of he Reichsmusikammer, a Nazi cultural enforcement agency set up to stamp out "alien" music. After the German defeat at Stalingrad in 1943 restrictions became more severe.

[above images from http://leroidesbelges.wordpress.com and http://www.return2style.de]

Under the Third Reich, action against jazz bands and their fans was uncoordinated and ambiguous. Municipal authorities, police, Nazi party functionaries and the SS initially tried to stamp out the music but the 1936 Berlin Ol;ympics meant that repressive policies were temporarily relaxed.and then tightened again after 1938 under the leadership of he Reichsmusikammer, a Nazi cultural enforcement agency set up to stamp out "alien" music. After the German defeat at Stalingrad in 1943 restrictions became more severe.

These two paintings by Otto Dix, the famous German artist of the Wemar Republic whose work was detested by the Nazis and concdemned as degenerate, uses jazz, negro musicians and the saxophone to refer to features of life in 1920s urban Germany. His work was removed from galleries and museums, and some of it was confiscated or destroyed.

The glowering central figure in the ironically-titled 1922 painting 'To Beauty' [above left] is Dix himself. Note the triumphant negro musician with an American flag in his pocket and drums featuring an American Indian. The painting above left is the central panel from Dix's famous triptych of 1927-8: Grossstadt [Big City] which again features a negro musician and a jazz combo with a conspicuous saxophone, as well as a Charlestoning couple. For Dix, and for many Germans, jazz in its manifestations was a symbol of urban modernity in the shell-shocked post-war Germany. For the Nazis it represented inter-racial mixing, permissiveness and a rejection of 'traditional' German values.

The glowering central figure in the ironically-titled 1922 painting 'To Beauty' [above left] is Dix himself. Note the triumphant negro musician with an American flag in his pocket and drums featuring an American Indian. The painting above left is the central panel from Dix's famous triptych of 1927-8: Grossstadt [Big City] which again features a negro musician and a jazz combo with a conspicuous saxophone, as well as a Charlestoning couple. For Dix, and for many Germans, jazz in its manifestations was a symbol of urban modernity in the shell-shocked post-war Germany. For the Nazis it represented inter-racial mixing, permissiveness and a rejection of 'traditional' German values.

Nazi Attitudes Towards Jazz and the Swing Kids

Officially, the Third Reich condemned jazz as early as 1933. But by the mid-1930s several "orchestras" openly performed Benny Goodman-style jazz in Berlin, including top hotels frequented by high-ranking Nazis. Although But during the war they faced a problem. Swing music and dancing was popular with troops and civilians alike, even though "social dancing" appears to have been banned in some places. Swing was also popular with members of the armed forces and was regarded as boosting morale while the news from the battle fronts gradually got increasingly sombre. So the Reich's response - largely due to the shrewdness of Josef Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda and Enlightentment - was confusingly ambiguous and uncorordinated even to the extent of condoning the broadcasting of some swing music and permitting the publication of material about swing music. For Goebbels, a happy soldier meant a better warrior. A few German bands were allowed to perform and record swing music. But many German jazz musicians were gradually conscripted into war duties - sometimes replaced by foreign musicians from Italy, Holland and Belgium. Goebbel's Ministry even arranged for such groups to entertain troops on furlough in concerts at major ballrooms and hotels. Some of these 'orchestras' were sent to to entertain front-line troops in their messes and barracks, where the officers seem to have made it clear that they wanted jazz of an uninhibited variety. A leading Nazi cultural bureaucrat, Hans Hinkel, once accomnpanied a jazz group to a concert in Occupied France, where he unwisely told troops that 'Jewish' and "Anglo-American' tunes would not be played. The angry audience pelted him with apples until he changed his mind.

[Michael Kater, Different Drummers: jazz in the culture of Nazi Germany [New York:1992], p.118

The best known of these was the group known by the innocuous and not very jazz-sounding name of "Charlie and his Orchestra." The historian Michael Kater decribes the group as "a special combination of sterling jazz players called together by Goebbel's ministry in the service of Nazi propaganda." Kater concludes that Charlie's Orchestra was "the most bizarre phenomenon both in the history of Nazi popular culture and the Reich's strenuous propaganda effort." [Kater, p.130] The reasons behind Goebbel's decisons were cynically clever. Goebbels wanted German radio to broadcast some music that would appeal to neighbouring countries and Britain and to act a sweetener to encourage listeners to stay tuned to the propaganda broadcasts in which Charlie's Orchestra's jazz was embedded. This music was broadcast to Britain in the programmes of William Joyce, a British fascist in Berlin, nick-named Lord Haw-Haw by his British listeners (he had a braying upper-class accent). However, his broadcasts were popular in the UK not because of their musical content but because they announced the names of captured British POWs, [Kater, pp.130-135]

The band, formed in 1940, made studio recordings which were released on disk in some of these countries. Their music was regularly broadcast to the British Isles. Some listeners in Canada and the USA claim that they were able to hear German shortwave broadcasts of the band.

Charlie and his Orchestra was formed by German saxophonist Lutz Templin, an admirer of swing. It included clarinetist clarinetist Kurt Abraham and trombone player Willy Berking, and was led by crooner Charlie Schwedler. He had a fine command of English and a knack for hijacking popular swing songs and replacing their lyrics with anti-semitic, anti-Allied lyrics.

"Mr Churchill, how do you do?

Hello, hello

Your famous convoys are not coming through ...."

Or this 1941 lyric based on the jstandard "Slumming on Park Avenue"

Here is the latest song of the British airmen:

Let's go bombing, oh, let's go bombing,

just like good old British airmen do.

Let us bomb the Frenchmen who were

once our allies!

England fights for liberty, we make them realize,

from the skies.

Let's go shelling where they're dwelling,

shelling Nanette, Fifi and Lulu.

Let us go to it, let's do it, let's sink

their food-ships too.

Let's go bombing, it's becoming quite the thing to do.

Not exactly witty or romantic, but the music not the words were the main thing and Charlie and his orchestra were very popular in Gertmany and in parts of occupied Europe. Modern assessments of the band's actual abilities assess it as competent at best but

[Michael Kater, Different Drummers: jazz in the culture of Nazi Germany [New York:1992], p.118

The best known of these was the group known by the innocuous and not very jazz-sounding name of "Charlie and his Orchestra." The historian Michael Kater decribes the group as "a special combination of sterling jazz players called together by Goebbel's ministry in the service of Nazi propaganda." Kater concludes that Charlie's Orchestra was "the most bizarre phenomenon both in the history of Nazi popular culture and the Reich's strenuous propaganda effort." [Kater, p.130] The reasons behind Goebbel's decisons were cynically clever. Goebbels wanted German radio to broadcast some music that would appeal to neighbouring countries and Britain and to act a sweetener to encourage listeners to stay tuned to the propaganda broadcasts in which Charlie's Orchestra's jazz was embedded. This music was broadcast to Britain in the programmes of William Joyce, a British fascist in Berlin, nick-named Lord Haw-Haw by his British listeners (he had a braying upper-class accent). However, his broadcasts were popular in the UK not because of their musical content but because they announced the names of captured British POWs, [Kater, pp.130-135]

The band, formed in 1940, made studio recordings which were released on disk in some of these countries. Their music was regularly broadcast to the British Isles. Some listeners in Canada and the USA claim that they were able to hear German shortwave broadcasts of the band.

Charlie and his Orchestra was formed by German saxophonist Lutz Templin, an admirer of swing. It included clarinetist clarinetist Kurt Abraham and trombone player Willy Berking, and was led by crooner Charlie Schwedler. He had a fine command of English and a knack for hijacking popular swing songs and replacing their lyrics with anti-semitic, anti-Allied lyrics.

"Mr Churchill, how do you do?

Hello, hello

Your famous convoys are not coming through ...."

Or this 1941 lyric based on the jstandard "Slumming on Park Avenue"

Here is the latest song of the British airmen:

Let's go bombing, oh, let's go bombing,

just like good old British airmen do.

Let us bomb the Frenchmen who were

once our allies!

England fights for liberty, we make them realize,

from the skies.

Let's go shelling where they're dwelling,

shelling Nanette, Fifi and Lulu.

Let us go to it, let's do it, let's sink

their food-ships too.

Let's go bombing, it's becoming quite the thing to do.

Not exactly witty or romantic, but the music not the words were the main thing and Charlie and his orchestra were very popular in Gertmany and in parts of occupied Europe. Modern assessments of the band's actual abilities assess it as competent at best but

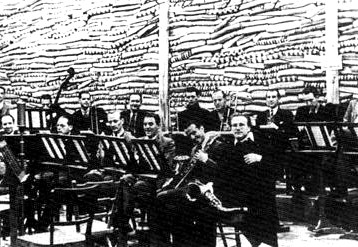

Charlie and his Orchestra in the studio [above left] and playing in a hotel in 1942 [above right]. Their music is still available on some specialist CDs and DVDs.

|

|

|