Scott (and Zelda and Scottie) Fitzgerald Go to Hollywood

F.Scott Fitzgerald and Hollywood

The two images above mark the first and the final stages of Scott Fitzgerald's time in Hollywood as a scriptwriter.

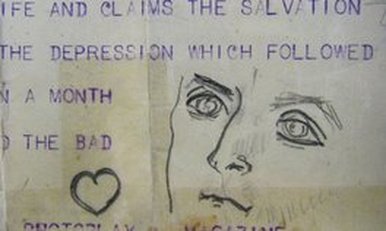

The first image is a section from a crumpled telegram, containing a sketch of the author (and a heart) by his wife, Zelda. The telegram,was sent to Scott from the editor of Photoplay magazine in January, 1927 a year or so after the publication of The Great Gatsby.It asked him to write an "editorial" of five hundred words giving the perspective of "youth" on the 1920s. At this time, Fitzgerald was at the height of his fame, earning large amounts of money for his short stories. The telegram reached him in Hollywood, where he was working on the script for Lipstick, intended to be a movie about flappers, a category famously an flamboyantly embodied by Zelda. Ominously, the script was never completed, the movie never made.

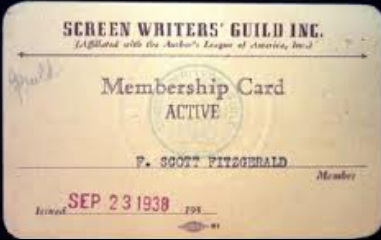

The second image, little over a decade later, signifies the third and final stage of Fitzgerald's scriptwriting career in Hollywood. By now his literary fame had receded, his work was unfashionable and he was desperately short of the money needed to pay for his drinking, the upkeep of his daughter and the institutionalisation of Zelda. Death was only a few months away.

The first image is a section from a crumpled telegram, containing a sketch of the author (and a heart) by his wife, Zelda. The telegram,was sent to Scott from the editor of Photoplay magazine in January, 1927 a year or so after the publication of The Great Gatsby.It asked him to write an "editorial" of five hundred words giving the perspective of "youth" on the 1920s. At this time, Fitzgerald was at the height of his fame, earning large amounts of money for his short stories. The telegram reached him in Hollywood, where he was working on the script for Lipstick, intended to be a movie about flappers, a category famously an flamboyantly embodied by Zelda. Ominously, the script was never completed, the movie never made.

The second image, little over a decade later, signifies the third and final stage of Fitzgerald's scriptwriting career in Hollywood. By now his literary fame had receded, his work was unfashionable and he was desperately short of the money needed to pay for his drinking, the upkeep of his daughter and the institutionalisation of Zelda. Death was only a few months away.

Scott Fitzgerald and the movies

"Chorus Girl's Romance" - based on a Fitzgerald story.

"I hate the place [Hollywood] like poison with a sincere hatred," Fitzgerald wrote to his agent in 1935. Since the resurrection of Fitzgerald's literary reputation over the last two or three decades, his relationship with Hollywood has usually been depicted as that of a tormented literary genius, needing money and so forced to waste his talents writing screenplays in a city he despised for a bunch of philistines who were incapable of recognising his remarkable talents. This failure to acknowledge his gifts, according to this scenario, helped destroy this sensitive icon of 20th Century American literature.

Fitzgerald himself occasionally promoted this myth of an author whose talents were unappreciated by the cynical, uncouth, money-grabbing Hollywood studio producers. In 1936 he wrote that movies were a "mechanical and communal art that ... was capable of reflecting only the tritest thought, the most obvious emotion ... an art in which words were subordinate to images, where persopnality was worn down to the inevitable low gear of collaboration..... There was a ranking indignity, that to me had become almost an obsession, in seeing the power of the written word subordinated to another power, a more glittering, a grosser power...." He claimed that his three spells in Hollywood had ended in failure because he could not accept the necessity of collaboration over scripts and that, unlike his fellow scriptwriters, he was not a hack and would not turn out scripts to order.

Fitzgerald himself occasionally promoted this myth of an author whose talents were unappreciated by the cynical, uncouth, money-grabbing Hollywood studio producers. In 1936 he wrote that movies were a "mechanical and communal art that ... was capable of reflecting only the tritest thought, the most obvious emotion ... an art in which words were subordinate to images, where persopnality was worn down to the inevitable low gear of collaboration..... There was a ranking indignity, that to me had become almost an obsession, in seeing the power of the written word subordinated to another power, a more glittering, a grosser power...." He claimed that his three spells in Hollywood had ended in failure because he could not accept the necessity of collaboration over scripts and that, unlike his fellow scriptwriters, he was not a hack and would not turn out scripts to order.

|

Yet for most of his career Fitzgerald was infatuated with Hollywood and aspired to become a a famous writer of screenplays. In his youth he went to the movies frequently; he especially admired Birth of a Nation. As Alan Margolies points out, Fitzgerald "had been interested in, maybe fascinated by, movie-making from a very early period of his life." When he went to New York after World War I Fitzgerald wrote frantically and at first unsuccessfully. Significantly, his list of writings at that time placed his film scripts first. "I wrote movies. I wrote song lyrics. I wrote complicated advertising schemes. I wrote poems .... " When his collection of short stories entitled Flappers and Philosophers was published, Fitzgerald happily accepted the money Hollywood offered to turn two of them, "Head and Shoulders" (filmed as The Chorus Girl's Romance) and "The Off-Shore Pirates" into movies.

This Hollywood money was significant - eventually disastrous -for the struggling young author, Zelda Sayres, who had earlier rejected his proposal of marriage earlier on the grounds that he was poor. Now Fitzgerald telegraphed her I HAVE SOLD THE MOVIE RIGHTS OF HEAD AND SHOULDERS TO THE METRO COMPANY FOR TWENTY FIVE HUNDRED DOLLARS I LOVE YOU DEAREST GIRL. The wealth and opportunities that Hollywood offered writers like Fitzgerald was one of several factors that explains his love-hate relationship with what was now America's movie capital. He (and Zelda) also loved the social cachet and glamour it provided, the parties, the chance to socialise with movie idols, the prospect of having enormous audiences worldwide gaze with awe upon something the writer helped create. A successful screenwriter who worked with Fitzgerald claimed that "Scott would rather have written a movie than the Bible...." Fitzgerald, according to Budd Schulberg, "thought [movies] were the new art form." And Arthur Krystal in his fine article on Fitzgerald as a screenwriter maintains that he was "the first American novelist to take the movies seriously and the first to regard his own talent as a natural fit with Hollywood." Unfortunately, Fitzgerald's screenwriting talents were nowhere nearly as good as the author liked to believe. His three spells working in Hollywood produced great source material on which he eventually based The Last Tycoon and the Pat Hobby short stories, but they did not bring him the success he craved. [Sources above and below: Aaron Latham, "Crazy Sundays: Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood",http://fitzgerald.narod.ru/drama/latham-crazysund.html; Arthur Krystal, "Slow fade: F.Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood", New Yorker, 11 Nov.2009]; Judith S. Baughman http://www.sc.edu/fitzgerald/movies.html; Anne Margaret Daniel, "The Fitzgeralds in Hollywood, Times Literary Supplement, 16 May 2012; Charles McGrath, "Fitzgerald as Screenwriter", New York Times, 22 April, 2004; Nick Finke, "Fitzgerald's Ledger", Deadline Hollywood,

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button was a not very good short story that Fitzgerald sold to Hollywood in the early 1920s for $1000. It took nine decades before it was director David Fincher transformed the flimsy kernel of the story into an absorbing movie.

|

|

|

|

Fitzgerald's Hollywood ExperiencesWhen Fitzgerald , accompanied by Zelda went to Hollywood in 1927 he was at the peak of his literary career.That year his annual income was almost $30 000. He was rich, famous, a sensation in both the social and literary worlds, married to a woman whom newspapers and magazines as an emblem of the jazz age. His output included highly-praised best-sellers as This Side of Paradise, The Beautiful and the Damned and The Jazz Age. As Arthur Krystal notes, Fitzgerald "wanted to be both a great novelist and a Hollywood hotshot," never acknowledging that the two aims were incompatible. Ominously, his most recent novel, 1925's The Great Gatsby, had received some indifferent reviews and lacklustre sales. His is career -and Zelda's - was about to deflate in one of those reversals of fortune depicted so melodramatically in Hollywood biopics.

Fitzgerald's was invited to Hollywood in 1927 to write a flapper comedy, Lipstick, with a $3500 advance. "I honestly believed," he later wrote, "that with no effort on my part I was a sort of magician with words; an odd delusion on my part when I had worked to so desperately hard to develop a hard colorful prose style .... Total result: a great time + no work." The author and Zelda partied frantically during their couple of months in Hollywood, living in luxury at the Hollywood Hotel; no script was ever produced." Zelda wrote to their daughter, six year old Scottie (deposited with her parents) that Scott "says he will never write another picture again because it is too hard, but I do not think writers mean what they say when they write about work.". Zelda also told Scottie that her parents had seen the 1926 movie of The Great Gatsby at a Hollywood theater. "It's ROTTEN and awful and terrible and we left.". After a few weeks the pair left LA, collected their daughter and went back to Europe. When Fitzgerald returned to Hollywood in July, 1937, he was no longer the fabled figure he had been. His literary reputation and income had both collapsed, he had spent most of the thirties in the grip of alcoholism, Zelda's fragile constitution and mentality had resulted in her institutionalisation. In order to pay for her treatment and his daughter Scottie's education and upkeep, he went to Hollywood again for his final stint as a scriptwriter, working in a small office at MGM. Initially, he was paid $1000 a week for six months, eventually increased to $1250 a week for a year at a time when the average yearly wage was $1780. Budd Schulberg described Fitzgerald at this stage as "tired, sick, embattled, vain and proud and painfully conscious of his fall from fame." Although he described himself as "a pretty broken and prematurely old man who hasn't a penny except what he can get oiut of a weary mind and a sick body." |

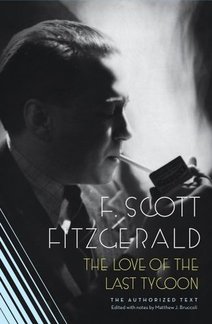

When Fitzgerald died in 1940 he left the unfinished manuscript of a novel about Hollywood, The Love of the Last Tycoon, whose main character Monroe Stahr was based on MGM's remarkable executive Irving Thalberg. The novel has usually been published under the title The Last Tycoon; although unfinished, it shows Fitzgerald at his best, partly because he had at last overcome his self-conscious, mannered, cloying style that mars most of his work.

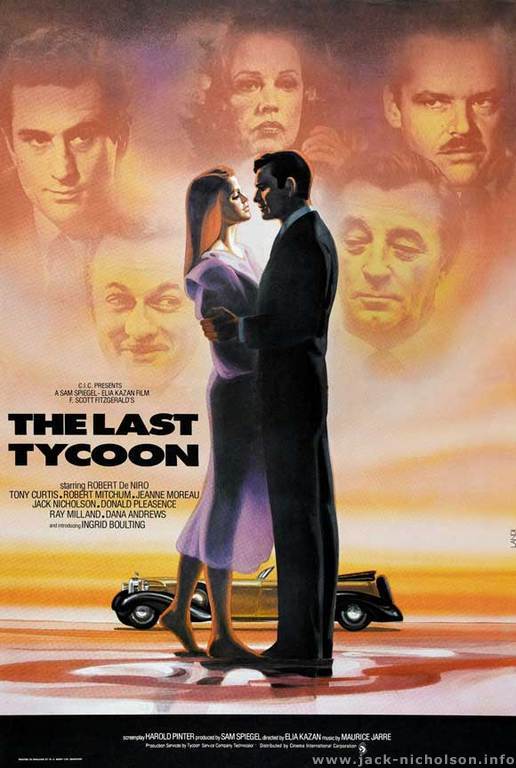

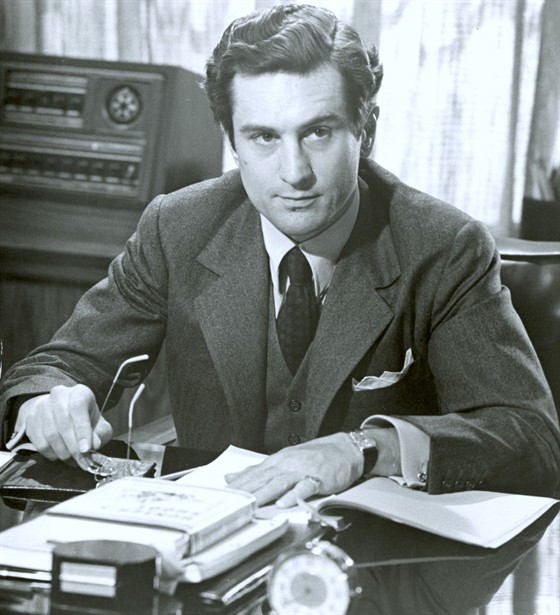

In 1976 director Elia Kazan made an interesting but not entirely successful movie - his last one. Its script was by Harold Pinter and it starred Robert De Niro in one of his best, most restrained and sympathetic performances. Tony Curtis, Donald Pleasance and Robert Mitchum were also very good, overshadowing Jack Nicholson who seemed out of his depth.

In 1976 director Elia Kazan made an interesting but not entirely successful movie - his last one. Its script was by Harold Pinter and it starred Robert De Niro in one of his best, most restrained and sympathetic performances. Tony Curtis, Donald Pleasance and Robert Mitchum were also very good, overshadowing Jack Nicholson who seemed out of his depth.