Sergeant Rutledge

Director John Ford, 1960

One of director John Ford's last westerns, Sergeant Rutledge was not a box office success, and it met with a mixed critical reception in the USA. Fifty years on, this mixture of cavalry western and courtroom drama can now be seen as one of Ford's most intriguing movies. The movie's subject-matter also offers some valuable insights into the controversial issue of race in early 1960s America, as well as throwing some light on Ford's attitudes towards racial minorities. Sergeant Rutledge seems to be Ford's attempt to redeem himself for a frequently criticised feature of his Westerns: their use of racial / ethnic stereotypes, most often found in his depictions of Native Americans.

Ford's "cavalry westerns" are justly famous, but this one is different. The film is about a very unusual cavalry unit, the Ninth, known as

"buffalo soldiers" - black soldiers, most of them freed slaves, led by a white officer. One of the Ninth, Sergeant Braxton Rutledge is facing a court-martial on the racially inflammatory charges of rape and murder of a young white girl and the murder of her father, the post commander. Although Rutledge has an exemplary record, the local townsfolk assume he is guilty because he is black. The prosecuting officer also shares these racist attitudes. The officer assigned to defend him not only has to deal with these difficulties; he also has to overcome Rutledge's belief that it is inevitable that his court-martial and the wider white community will find him guilty because of their racial prejudices.

Sergeant Rutledge was a special movie for Ford. It was the first movie made by a big Hollywood studio (Warner Bros) in which an African-American has the dominant roleFor its time it was bold in that it examined racism in the light of whites' fears of black male sexuality. For the first time in any of his many films the hero is a black man, Sergeant Braxton Rutledge. Not only is he portrayed onscreen as a person of courage, gravitas and dignity, but Ford films him in such a way as to make him a truly iconic figure, filling the role usually played by John Wayne.

In fact, Ford deliberately gives the character of Rutledge the same sort of iconic treatment he usually gave to characters played by John Wayne: a quiet and unassuming dignity, an air of physical and moral strength, and an aura of indomitability. Ford not only overcame Jack Warner's preference for either Sidney Poitier or Harry Belafonte in the title role -"they weren't tough enough" was the veteran director's verdict. He spent some time coaching Strode (whose wife had gone to school with some of Ford's children) in the requirements of his role. Stode himself regarded his performance as his career best and in his biography expressed his gratitude for Ford's mentorship. He wrote that "[Ford} knew how to pluck me like a harp.... I almost had a nervous breakdown doing Sergeant Rutledge but it helped me become an actor." Strode was especially proud of the scene where Rutledge returns to help his cavalry unit when, outnumbered, they are attacked by Apaches. "You never seen a negro come off a mountain like John Wayne before. I had the greatest Glory Hallelujah ride across the Pecos River [...] I carried the whole black race across that river."

This is one of the very few movies made about the United States army's "buffalo soldiers". This was the term given to black soldiers of the Ninth and Tenth cavalry units in post-Civil War America (most ot them were, like Rutledge, freed slaves). They figured prominently in the Indian wars in the later nineteenth Century. As in the movie, they had white officers. Sergeant was apparently the top rank they were allowed to attain. Their infantry equivalents could be found in the Twenty-fourth and Twenty-Fifth Infantry divisions. According to the movie -and most other accounts - the buffalo soldiers got their name from the buffalo furs they wore in winter. According to the Buffalo Soldier Museum website "Some attribute it to the Indians likening the short curly hair of the black troopers to that of the buffalo. .... Others say that when the American bison was wounded or cornered, it fought ferociously, displaying uncommon stamina and courage, identical to the black man in battle. "[http://buffalosoldiermuseum.com/category/9th-10th-cavalry-regiment] In Sergeant Rutledge the buffalo soldiers are presented as brave , self-reliant and capable men, especially in the scene where they thwart an Indian attack.

Ford's "cavalry westerns" are justly famous, but this one is different. The film is about a very unusual cavalry unit, the Ninth, known as

"buffalo soldiers" - black soldiers, most of them freed slaves, led by a white officer. One of the Ninth, Sergeant Braxton Rutledge is facing a court-martial on the racially inflammatory charges of rape and murder of a young white girl and the murder of her father, the post commander. Although Rutledge has an exemplary record, the local townsfolk assume he is guilty because he is black. The prosecuting officer also shares these racist attitudes. The officer assigned to defend him not only has to deal with these difficulties; he also has to overcome Rutledge's belief that it is inevitable that his court-martial and the wider white community will find him guilty because of their racial prejudices.

Sergeant Rutledge was a special movie for Ford. It was the first movie made by a big Hollywood studio (Warner Bros) in which an African-American has the dominant roleFor its time it was bold in that it examined racism in the light of whites' fears of black male sexuality. For the first time in any of his many films the hero is a black man, Sergeant Braxton Rutledge. Not only is he portrayed onscreen as a person of courage, gravitas and dignity, but Ford films him in such a way as to make him a truly iconic figure, filling the role usually played by John Wayne.

In fact, Ford deliberately gives the character of Rutledge the same sort of iconic treatment he usually gave to characters played by John Wayne: a quiet and unassuming dignity, an air of physical and moral strength, and an aura of indomitability. Ford not only overcame Jack Warner's preference for either Sidney Poitier or Harry Belafonte in the title role -"they weren't tough enough" was the veteran director's verdict. He spent some time coaching Strode (whose wife had gone to school with some of Ford's children) in the requirements of his role. Stode himself regarded his performance as his career best and in his biography expressed his gratitude for Ford's mentorship. He wrote that "[Ford} knew how to pluck me like a harp.... I almost had a nervous breakdown doing Sergeant Rutledge but it helped me become an actor." Strode was especially proud of the scene where Rutledge returns to help his cavalry unit when, outnumbered, they are attacked by Apaches. "You never seen a negro come off a mountain like John Wayne before. I had the greatest Glory Hallelujah ride across the Pecos River [...] I carried the whole black race across that river."

This is one of the very few movies made about the United States army's "buffalo soldiers". This was the term given to black soldiers of the Ninth and Tenth cavalry units in post-Civil War America (most ot them were, like Rutledge, freed slaves). They figured prominently in the Indian wars in the later nineteenth Century. As in the movie, they had white officers. Sergeant was apparently the top rank they were allowed to attain. Their infantry equivalents could be found in the Twenty-fourth and Twenty-Fifth Infantry divisions. According to the movie -and most other accounts - the buffalo soldiers got their name from the buffalo furs they wore in winter. According to the Buffalo Soldier Museum website "Some attribute it to the Indians likening the short curly hair of the black troopers to that of the buffalo. .... Others say that when the American bison was wounded or cornered, it fought ferociously, displaying uncommon stamina and courage, identical to the black man in battle. "[http://buffalosoldiermuseum.com/category/9th-10th-cavalry-regiment] In Sergeant Rutledge the buffalo soldiers are presented as brave , self-reliant and capable men, especially in the scene where they thwart an Indian attack.

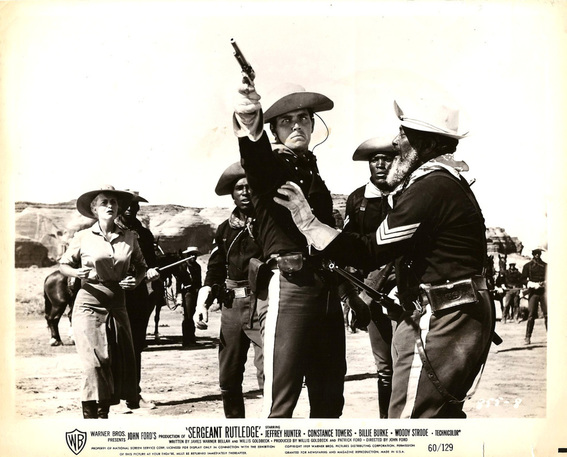

Ford deliberately filmed Strode as Rutledge as a commanding , dignified and imposing presence, much as he usually presented the image of John Wayne onscreen. The two above images from the movie illustrate this approach.

Many of the features of Sergeant Rutledge are the familiar tropes of John Ford's westerns. As these images above indicate, they include such Ford favourites as Monument valley settings, the U.S. Cavalry, special 'communities' such as the cavalry unit, the courthouse, and the local townsfolk.

BLACK MAN, WHITE WOMAN

But there's a significant twist in Ford's portrayal of the movie's heroine, Mary Beecher (very effectively played by Constance Towers). Ford provides her with a conventional movie romance with a handsome young army officer Lt. Tom Cantrell (Jeffrey Hunter), but the director is obviously not very interested in this aspect. Instead he subversively uses the character of Mary Beecher to explore the issue of race and sex. In an eerie early sequence Ford plays on the audience's assumptions / expectations. In a scene set in a deserted and fog-bound railroad depot (Spindle Station) we see a frightened, beautiful young white woman looking nervously through the fog. In a sudden close-up a black hand is clasped over her mouth. Everything seems set up for a scene embodying a stereotyped cinematic version of black / coloured male as sexual predator victimising a defenceless young white woman.

This racial stereotype still has its advocates today. Dylann Roof, the killer of nine members of a Charleston African-American church prayer meeting in June, 2015, claimed that “I have to do it . You rape our women and you’re taking over our country. And you have to go.” Heidy Beirich, head of the

Southern Poverty Law Center’s intelligence project, which tracks the activity of American hate groups, commented that "the specter of white women being sexually assaulted by black men ... is probably the oldest racist trope we have in the U.S.” [New York Times, 18 June, 2015]

The local community assumes that the fact that Rutledge is a negro means he must be guilty of rape and murder. This is assumed by the crowd of locals who attend the courtroom sessions, including its gossipy and rather stupid older women who profess to be shocked by Mary Beecher spending the nixt in proximity with a black man.

At this initial stage Sergeant Rutledge looks like it's going to be a variant of what scholars now call a "captivity narrative" (Ford's earlier, much more famous The Searchers is a prime example), a genre that encompasses more than western movies. In the typical captivity narrative a captive or endangered white woman represents "the values of Christianity and civilisation" which are threatened by her savage and rapacious captor(s). Her resistance, often futile, of these predations display her Christian and civilized virtues. [See Glenn Frankel's The Searchers The Making of an American Legend (London: Bloomsbury).

But Sergeant Rutledge immediately overturns and subverts this conventional narrative. Far from capturing / raping / molesting / Mary Beecher, the black Sergeant acts as her protector and defender and returns her safely to her white white community instead of taking her away from it. As the film progresses it becomes clear that the only threat to Mary Beecher's sexual purity comes from the malicious gossip of members of that community. Her sturdy defence of Rutledge's behaviour at the depot and her eyewitness assertions that he is innocent of the charges and rape and murder are met with skepticism, and her morality is questioned.

Many of the features of Sergeant Rutledge are the familiar tropes of John Ford's westerns. As these images above indicate, they include such Ford favourites as Monument valley settings, the U.S. Cavalry, special 'communities' such as the cavalry unit, the courthouse, and the local townsfolk.

BLACK MAN, WHITE WOMAN

But there's a significant twist in Ford's portrayal of the movie's heroine, Mary Beecher (very effectively played by Constance Towers). Ford provides her with a conventional movie romance with a handsome young army officer Lt. Tom Cantrell (Jeffrey Hunter), but the director is obviously not very interested in this aspect. Instead he subversively uses the character of Mary Beecher to explore the issue of race and sex. In an eerie early sequence Ford plays on the audience's assumptions / expectations. In a scene set in a deserted and fog-bound railroad depot (Spindle Station) we see a frightened, beautiful young white woman looking nervously through the fog. In a sudden close-up a black hand is clasped over her mouth. Everything seems set up for a scene embodying a stereotyped cinematic version of black / coloured male as sexual predator victimising a defenceless young white woman.

This racial stereotype still has its advocates today. Dylann Roof, the killer of nine members of a Charleston African-American church prayer meeting in June, 2015, claimed that “I have to do it . You rape our women and you’re taking over our country. And you have to go.” Heidy Beirich, head of the

Southern Poverty Law Center’s intelligence project, which tracks the activity of American hate groups, commented that "the specter of white women being sexually assaulted by black men ... is probably the oldest racist trope we have in the U.S.” [New York Times, 18 June, 2015]

The local community assumes that the fact that Rutledge is a negro means he must be guilty of rape and murder. This is assumed by the crowd of locals who attend the courtroom sessions, including its gossipy and rather stupid older women who profess to be shocked by Mary Beecher spending the nixt in proximity with a black man.

At this initial stage Sergeant Rutledge looks like it's going to be a variant of what scholars now call a "captivity narrative" (Ford's earlier, much more famous The Searchers is a prime example), a genre that encompasses more than western movies. In the typical captivity narrative a captive or endangered white woman represents "the values of Christianity and civilisation" which are threatened by her savage and rapacious captor(s). Her resistance, often futile, of these predations display her Christian and civilized virtues. [See Glenn Frankel's The Searchers The Making of an American Legend (London: Bloomsbury).

But Sergeant Rutledge immediately overturns and subverts this conventional narrative. Far from capturing / raping / molesting / Mary Beecher, the black Sergeant acts as her protector and defender and returns her safely to her white white community instead of taking her away from it. As the film progresses it becomes clear that the only threat to Mary Beecher's sexual purity comes from the malicious gossip of members of that community. Her sturdy defence of Rutledge's behaviour at the depot and her eyewitness assertions that he is innocent of the charges and rape and murder are met with skepticism, and her morality is questioned.

The early sequence at Spindle Station, an isolated railroad depot whose stationmaster has just been murdered, leaving Mary Beecher apparently alone and in danger from Mescalino Indians, deliberately plays on audience assumptions about black men as sexual predators. Ford succinctly emphasises the woman's vulnerability in the darkness and fog, then briefly establishes the black soldier's apparent menace as he clasps his hand over her mouth, only to overturn such assumptions as he demonstrates the sergeant's caring, dignified and protective behaviour as the pair shelter in the depot for the night.

Rutledge is assumed guilty of murder and rape by virtue of his race not only by the local community who attend his trial and who increasing appear as a lynch mob in the making with their comments and threats. The prosecuting officer Captain Shuttock also equates Rutdledge's race with criminality during his summation. Furthermore the members of the trial-board also make this assumption during a card-game break in the course of the trial. Rutledge himself takes it for granted that his 'blackness' will be the key factor in establishing his 'guilt'.

Rutledge is assumed guilty of murder and rape by virtue of his race not only by the local community who attend his trial and who increasing appear as a lynch mob in the making with their comments and threats. The prosecuting officer Captain Shuttock also equates Rutdledge's race with criminality during his summation. Furthermore the members of the trial-board also make this assumption during a card-game break in the course of the trial. Rutledge himself takes it for granted that his 'blackness' will be the key factor in establishing his 'guilt'.

The Visual Implications of the Movie's Posters

Throughout the movie Ford deliberately focuses on the racial and sexual overtones of the white woman / black men issue. He has Mary consistently defend Rutledge's behaviour and moral character despite the displeasure this causes the local community. And in one key scene she is shown cradling caring for wounded buffalo soldiers, inclusing cradling a young black soldier in her arms. Such scenes must upset many racially prejudiced whites in American audiences in 1960: it's not surprising the movie did not do well in the USA. At that time several of the states had miscegenation laws and most southern states had strict segregation laws.

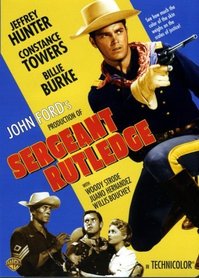

The movie's posters and visual advertisements provide a revealing backdrop to its subject of racism. Some of the posters omit Rutledge entirely - although he is is the central character and its hero.

|

Note the billing in both posters. Woody Strode as Rutledge is the movie's key character with most on-screen time. But he's not given the prestigious above-the-title billing in Poster 1, not the dominant top three billing in Poster 2. In fact. third billing in both posters belongs to Billie Burke, who plays one of the movie's minor characters.

And check out Strode's skin tone in Poster 2: it has been toned down to almost match that of white star Jeffrey Hunter. |

|

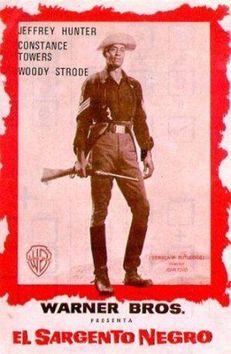

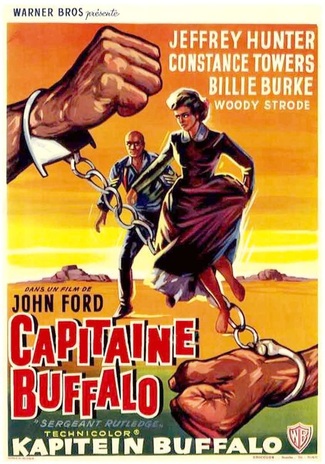

Both Poster 3 and 4 share blunt titles: 'The Black Captain'. Poster 3 is a Spanish-langiage version, very likely aimed at the Mexican market. Here Woody Strode shares top billing (Billie Burke's name has vanished) and his forceful stance completely dominates the poster. A French poster (4) gives the directyor John Ford the only above the title billing, and Stode is again relegated to an inferior name credit. But at least he figures prominently, if passively, in the image. It looks as if the female lead is protecting him from the white male lead.

|

Poster 5 was for the German market. Its title is "The Black Sergeant: One Foot in Hell". Note the minor placement of Strode's name. Poster 6 "Captain Buffalo" contains two languages, French and Dutch. This poster gives Strode a slightly larger name credit. Both posters emphasise that it's a John Ford movie.

INterestingly, both these posters portray Rutledge as both criminalised ( handcuffs) and menacing. He seems to be pursuing the fleeing white woman with evil intent. This suggests that the predatory black would-be rapist motif was certainly not confined to the USA.

INterestingly, both these posters portray Rutledge as both criminalised ( handcuffs) and menacing. He seems to be pursuing the fleeing white woman with evil intent. This suggests that the predatory black would-be rapist motif was certainly not confined to the USA.

|

|

|

The Civil Rights Background to Sergeant Rutledge

When John Ford made Sergeant Rutledge, the debate over black civil rights was already a major issue in American society. Only six years earlier the Supreme Court had ruled that segregation was unconstitutional. The ruling had been met with bitter opposition, often abusive and violent, in the American south and in some other areas, Since then civil rights issues had constantly been in the foreground of public attention. Groups such as the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Council had astutely used legal action, peaceful demonstrations and marches to draw public attention to unfair treatment of blacks and to gain sympathy for their cause. The 1955 Montgomery bus boycott A charismatic black leader, Martin Luther King Jr, a man with great media appeal, was becoming the focus and voice of the invigorated civil rights movement. In 1957 Congress had passed a Civil Rights Act establishing a Civil Rights Commission and ordering the Justice Dept to investigate denial of black voting rights in the South. A few months before the release of Sergeant Rutledge, passions had erupted at Little Rock High School, forcing President Eisenhower to send federal troops to enable a handful of black students to enrol in the previously segregated Alabama school.

1950s Hollywood and the Rise of African-American Movie Stars

When John Ford made Sergeant Rutledge, the debate over black civil rights was already a major issue in American society. Only six years earlier the Supreme Court had ruled that segregation was unconstitutional. The ruling had been met with bitter opposition, often abusive and violent, in the American south and in some other areas, Since then civil rights issues had constantly been in the foreground of public attention. Groups such as the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Council had astutely used legal action, peaceful demonstrations and marches to draw public attention to unfair treatment of blacks and to gain sympathy for their cause. The 1955 Montgomery bus boycott A charismatic black leader, Martin Luther King Jr, a man with great media appeal, was becoming the focus and voice of the invigorated civil rights movement. In 1957 Congress had passed a Civil Rights Act establishing a Civil Rights Commission and ordering the Justice Dept to investigate denial of black voting rights in the South. A few months before the release of Sergeant Rutledge, passions had erupted at Little Rock High School, forcing President Eisenhower to send federal troops to enable a handful of black students to enrol in the previously segregated Alabama school.

1950s Hollywood and the Rise of African-American Movie Stars

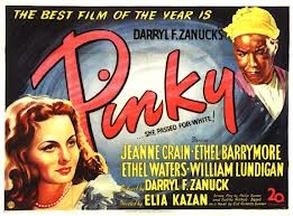

|

At the very end of the 1940s a major Hollywood studio (20th Century Fox) issued a movie under the imprimatur of one of the era's most famous producers, Darryl F. Zanuck, directed by an up-and-coming director, Elia Kazan. That 1949 movie, Pinky, not only had anAfrican-American (Ethel Waters) in a crucial role. It also dealt with a racial issue ignored by Hollywood and America for decades: black people whose light complexion enabled them to pass for whites, and the implications of this for themselves personally and their racial identity. The movie's heroine, played by the underrated white actress jeanne Crain, passes for white and has been living as a white in the North after fleeing the constrictions of her life in her native South. Pinky not only involves the taboo issue of miscegenation ( a crime in some southern states). It casts Pinky's grandmother (Waters) as a strong, independent person, proud of her racial identity and a mentor to her granddaughter who ultimately returns to the South to willingly accept her background as a person of colour.

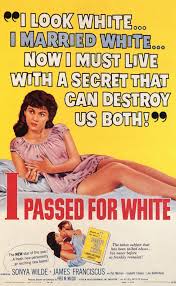

The fifties saw other movies that were significant for African-Americans. Not only were they being much more screen time. Some movies provided them with chances to step outside racial stereotypes. Sidney Poitier's portrayal of a capable, forthright and talented black student in the mid-50's hit Blackboard Jungle made him a star. One of the top Hollywood talents of the era, Otto Preminger, produced and directed a lavish, big screen, all-black musical Carmen Jones in 1954 . Three years later another producer-director Stanley Kramer teamed the then box-office idol Tony Curtis with Sidney Poitier in The Defiant Ones. Another top Hollywood director, Robert Wise, made a drama Odds Against Tomorrow in which Harry Belafonte topped the star billing list ahead of Robert Ryan (as a racist) and Shelley Winters.And at the end of the decade the issue of miscegenation and racial identity was treated explicitly in I Passed For White. |

|