The Imitation Game: Part 2

The truth about Turing, Colossus and the 'Bombe'

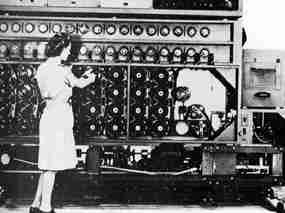

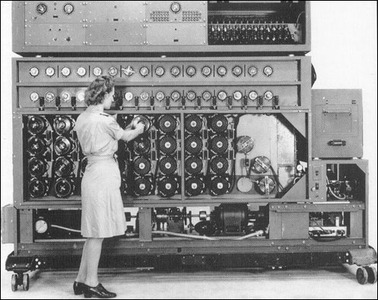

The Imitation Game spent a lot of time showing Turing and his team working on a strange looking machine (known as a 'Bombe' or 'Bomb') in one of Bletchley Park's 'sheds'. Although the movie makes it clear that this clinking, blinking, whirling device was instrumental in breaking the Enigma code by calculating daily settings of the Enigma machines used by the German military, the movie audience is left unclear as to exactly how the machine works. This is understandable. Figuring out the workings of the Bletchley machine requires an advanced knowledge of mathematics, statistics, electrical engineering, cryptography plus an occasional touch of linguistics .

According to the movie, Turing appears to be the inventor, chief designer, main advocate and key engineer of this device. It's beyond dispute that Turing , in the words of Douglas Hofstadter, the cognitive scientist, "spearheaded the science of computation." Hofstadter also provides a deft summary of Turing's life and accomplishments":

"Atheist, homosexual, eccentric, marathon-running English mathematician A.M. Turing was in large part responsible not only for the concept of computers, incisive theorems about their powers, and a clear vision of the possibilities of computer minds, but also for the cracking of German ciphers during the Second World War. It is fair to say that we owe much to Alan Turing for the fact that we are not under Nazi rule today."

[Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma Ibooks 2014 ed, p.12]

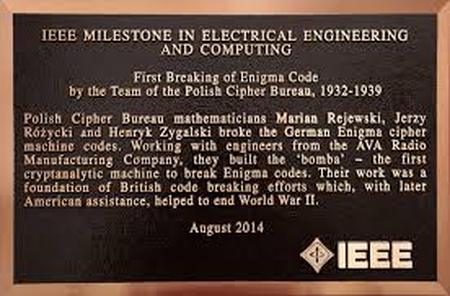

The movie Turing is shown as regarding it as his child, and giving it a name: Christopher. Misleading titles at the movie's end also suggest it was the prototype of what we now call 'computers'. This view is also frequently repeated in articles and books about computers, Bletchley Park and Turing. They also fail to acknowledge the role played by the Polish Cipher Bureau in devising an early Bombe before the war. Turing himself characterised his first attempt at Bombe-building in late 1939 as "resembling, but far larger than the Bombe of the Poles." [Hodges, p.24] As Turing's biographer Andrew Hodges points out, the Poles had already built six 'Bombes' by November 1938, . The origins of the term 'bombe' or 'bomb' are disputed. One simple explanation is that, viewed from above, a bombe resembled a delicious confectionary, the bombe glacée. But the boring truth is that the Polish Cipher Bureau, called the device a 'Bomba' because it ticked like a comic-strip or movie bomb. Essentially, the Polish Cipher Bureau discovered that the Enigma Machine's electrical circuitry could be exploited to reveal its enciphering secrets. According to Hodges, "the Poles were years ahead of the British, who were still were they had been in 1932." [Hodges, pp. 337-338]

However, although Turing's innovatory ideas on artifical intelligence and its theory before and after the war played a major part in the development of computers, the machine that is so lovingly depicted in The Imitation Game never was regarded as a prototype for computers. That honour belongs to another machine at Bletchley, nicknamed 'Colossus'. And credit for the design and development of Colossus does not belong to Turing (not that he claimed it) and his team depicted in at work in The Imitation Game. Its inventors and engineers have never received the post-1970s publicity given to Turing and the Bletchley codebreakers.

According to the movie, Turing appears to be the inventor, chief designer, main advocate and key engineer of this device. It's beyond dispute that Turing , in the words of Douglas Hofstadter, the cognitive scientist, "spearheaded the science of computation." Hofstadter also provides a deft summary of Turing's life and accomplishments":

"Atheist, homosexual, eccentric, marathon-running English mathematician A.M. Turing was in large part responsible not only for the concept of computers, incisive theorems about their powers, and a clear vision of the possibilities of computer minds, but also for the cracking of German ciphers during the Second World War. It is fair to say that we owe much to Alan Turing for the fact that we are not under Nazi rule today."

[Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma Ibooks 2014 ed, p.12]

The movie Turing is shown as regarding it as his child, and giving it a name: Christopher. Misleading titles at the movie's end also suggest it was the prototype of what we now call 'computers'. This view is also frequently repeated in articles and books about computers, Bletchley Park and Turing. They also fail to acknowledge the role played by the Polish Cipher Bureau in devising an early Bombe before the war. Turing himself characterised his first attempt at Bombe-building in late 1939 as "resembling, but far larger than the Bombe of the Poles." [Hodges, p.24] As Turing's biographer Andrew Hodges points out, the Poles had already built six 'Bombes' by November 1938, . The origins of the term 'bombe' or 'bomb' are disputed. One simple explanation is that, viewed from above, a bombe resembled a delicious confectionary, the bombe glacée. But the boring truth is that the Polish Cipher Bureau, called the device a 'Bomba' because it ticked like a comic-strip or movie bomb. Essentially, the Polish Cipher Bureau discovered that the Enigma Machine's electrical circuitry could be exploited to reveal its enciphering secrets. According to Hodges, "the Poles were years ahead of the British, who were still were they had been in 1932." [Hodges, pp. 337-338]

However, although Turing's innovatory ideas on artifical intelligence and its theory before and after the war played a major part in the development of computers, the machine that is so lovingly depicted in The Imitation Game never was regarded as a prototype for computers. That honour belongs to another machine at Bletchley, nicknamed 'Colossus'. And credit for the design and development of Colossus does not belong to Turing (not that he claimed it) and his team depicted in at work in The Imitation Game. Its inventors and engineers have never received the post-1970s publicity given to Turing and the Bletchley codebreakers.

The 'bombe' -the Polish as well as the British versions - was an electrical-mechanical computing device with a very special purpose. Unlike modern, general purpose, computers, the bombes could only solve one problem. In this case, it was designed to find the password keys or special main keys that operated the Enigma encoding system, and which altered every day - as the movie explains. Electricity passes through circuits which are then manipulated mechanically by dozens of rotating drums. These rotating drums are intended to copy the way the Enigma machine's set of rotors revolved when encrypting each letter typed by its operator.

Turing tried to break Enigma by working on the German navy's 'Home Waters' variant, nicknamed 'Dolphin' by the British. An important role, ignored by the movie, was played by Gordon Welchman, one of the Bletchley mathematicians, who organised an integrated unit dedicated to breaking Enigma. By early 1940 the group had deciphered several German Enigma codes, Green,Yellow and, especially important, Red, which was used by the Luftwaffe. Welchman also devised a 'diagonal board' for the Bombe, considerably improving Turing's original design and speeding up the deciphering process. In the movie Turing sends a letter to Churchill, requesting improved funding. In fact, the letter was a joint effort sent by Welchman, Turing and two other Bletchley staff.

The Imitation Game not only ignores Welchman's contribution to the Bombe. It also gives the visually and cinematically dramatic impression that Turing and his team designed and built the first Bombe at Bletchley. However, the much less cinematic reality is that while Turing provided the theoretical 'blueprint' of the Bombe, the job of converting abstract concept into electrical-mechanical engineering reality was not done by Turing's team. The engineering design and construction was the work of Harold "Doc" Keen , Chief Engineer the British Tabulating Machine Company, helped by his engineering team there. Keen was an electrical engineer who worked for years for BTM. By World War 2 he was the U.K.'s leading expert in punched card technology, with dozens of patents to his name. Keen and his BTM group applied their technical prowess at using electrical relays to perform logical functions in office calculators and sorters. They devised and made the relays that enabled the Bombe to do its job. [Hodges, pp. 351]

So the construction of the Bombers was not done at Bletchley under Turing's supervision. instead, the job was done miles from Bletchley at the BTM's factory at Letchford, 33 miles from Bletchley. And the intricate wiring work was done at a corset factory in the town. Security was deliberately low key. A completed Bombe was loaded into an army lorry at the loading bay (near car park), supervised by a solitary sentry. It was then sent to Bletchley - unescorted.

An interesting insight into the work at Letchford is provided by a youthful factory employee, Byal Richards:

" At work we were engaged in designing tools for making a mysterious secret naval project we only knew as ‘A23’. Thus just by chance I found I was in a reserved occupation for the rest of the war; this deferral was reviewed every few months and depended on performance.... It was not until nearly 50 years later that I discovered the parts we made were for ‘bombes’, electro-mechanical machines for unravelling the wheel settings for the keys of the German Enigma encipher. The ‘bombes’ were based on an original Polish ‘bomba’ which had decoded German military messages for some years. Throughout the war our machines decoded virtually all German military radio traffic, sometimes even before the intended recipients, later in conjunction with the ‘Colossus’ computer, and it is probable the war could have been lost without them.

We had no idea what the parts were for but there must have been hundreds of thousands of them in the many completed bombes which were large wardrobe-sized boxes full of whirring wheels or drums. Because the name ‘bombe’ leaked out some thought they were infernal devices to be dropped over Germany! (The name may have been given because they ‘ticked’). This work took precedence over everything and caused much overtime. Chief Engineer Harold ‘Doc’ Keen was in overall control while Tommy Wright and John Page produced the working blueprints which we often had amended to ease production."

Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/42/a2070442.shtml

So the construction of the Bombers was not done at Bletchley under Turing's supervision. instead, the job was done miles from Bletchley at the BTM's factory at Letchford, 33 miles from Bletchley. And the intricate wiring work was done at a corset factory in the town. Security was deliberately low key. A completed Bombe was loaded into an army lorry at the loading bay (near car park), supervised by a solitary sentry. It was then sent to Bletchley - unescorted.

An interesting insight into the work at Letchford is provided by a youthful factory employee, Byal Richards:

" At work we were engaged in designing tools for making a mysterious secret naval project we only knew as ‘A23’. Thus just by chance I found I was in a reserved occupation for the rest of the war; this deferral was reviewed every few months and depended on performance.... It was not until nearly 50 years later that I discovered the parts we made were for ‘bombes’, electro-mechanical machines for unravelling the wheel settings for the keys of the German Enigma encipher. The ‘bombes’ were based on an original Polish ‘bomba’ which had decoded German military messages for some years. Throughout the war our machines decoded virtually all German military radio traffic, sometimes even before the intended recipients, later in conjunction with the ‘Colossus’ computer, and it is probable the war could have been lost without them.

We had no idea what the parts were for but there must have been hundreds of thousands of them in the many completed bombes which were large wardrobe-sized boxes full of whirring wheels or drums. Because the name ‘bombe’ leaked out some thought they were infernal devices to be dropped over Germany! (The name may have been given because they ‘ticked’). This work took precedence over everything and caused much overtime. Chief Engineer Harold ‘Doc’ Keen was in overall control while Tommy Wright and John Page produced the working blueprints which we often had amended to ease production."

Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/42/a2070442.shtml