The Imitation Game: Turing, Bletchley and the Colossus Machine

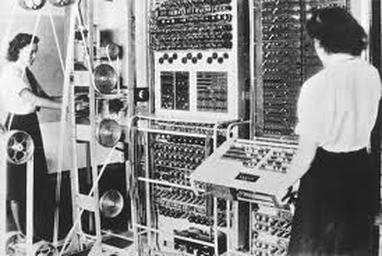

Two views of a Colossus machine at Bletchley Park. Eventually ten or twelve 'Colossi' were built . Left image shows a couple of the WREN officers who tended the machines. Howard Campaigne, one of the experts working on Colossus describes the Wrens as "very skilled and adroit.... Without the Wrens 1 was helpless."

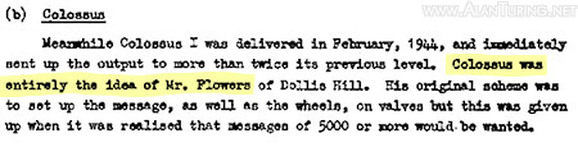

Colossus obviously was a completely different beast from the Bombe that features in The Imitation Game. The movie occasionally confuses the two different functions and tasks of the two technologies. Unfortunately, it also inaccurately continues the now discredited claims that Turing and his Bletchley team designed and built the machine that in 1944 cracked the particularly difficult German military encryptions used by Hitler and his high command. This machine was called Colossus. Turing statistical analysis theories offered insights but the essential breakthrough was carried out by Max Newman who, on reaching an impasse, handed the task over to a team of brilliant Post Officers electro-engineers led by Thomas Flowers and working in suburban London. In a few months Flowers and his team designed and built Colossus, and handed it over to Bletchley where it was put into immediate use.

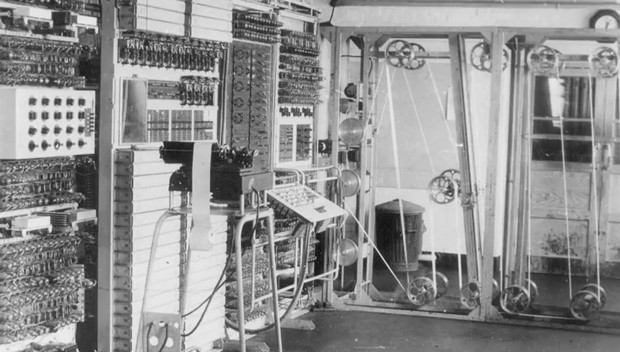

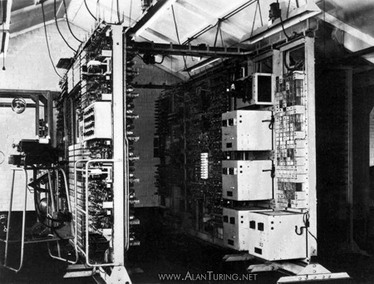

The side view of a Colossus [below,left) indicates the size and complexity of the machine. A recently reconstructed, working Colossus is shown below, right.

Colossus obviously was a completely different beast from the Bombe that features in The Imitation Game. The movie occasionally confuses the two different functions and tasks of the two technologies. Unfortunately, it also inaccurately continues the now discredited claims that Turing and his Bletchley team designed and built the machine that in 1944 cracked the particularly difficult German military encryptions used by Hitler and his high command. This machine was called Colossus. Turing statistical analysis theories offered insights but the essential breakthrough was carried out by Max Newman who, on reaching an impasse, handed the task over to a team of brilliant Post Officers electro-engineers led by Thomas Flowers and working in suburban London. In a few months Flowers and his team designed and built Colossus, and handed it over to Bletchley where it was put into immediate use.

The side view of a Colossus [below,left) indicates the size and complexity of the machine. A recently reconstructed, working Colossus is shown below, right.

What was the purpose of Colossus? And what was Turing's role?

The Colossus machine should not be confused with the Bombe. It was much more sophisticated, powerful and expensive, and worked on cracking a different and much more difficult and important German code.(nicknamed Tunny by the British). As one authority tersely concludes:

Alan Turing did not become the chief figure in the Tunny work, and in particular did not design or build the Colossus, as is often incorrectly stated. Colossus was not applied to Enigma ciphers! However, it depended on the statistical theory that Alan Turing had developed for breaking the naval Enigma.

[www.turing.org.uk/scrapbook/electronic.htm]

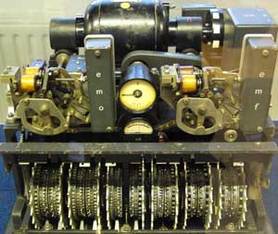

By 1943 the Germans were using their Enigma machines mainly for field work. But for high-level communications, including messages from Hitler and military headquarters including communication of military strategy and troop movements, the Germans were using a much more sophisticated encoding device. This used a different type of machine from Enigma: the teleprinter-based Lorenz SZ 40 and SZ 42 machines, designed by the AG Company. This was a bigger, heavier machine using fixed circuits and teleprinter mechanisms. It';s code-cracking capabilities were an incredible 5,429,503,678,976 times greater than the Enigma system. Bletchley Park had the advantage of using actual Enigma machines to help crack the Enigma code, but only after the D-Day landings did a couple of the SZ machines make their way to England. But by then the Tunny code had already been broken.

The Colossus machine should not be confused with the Bombe. It was much more sophisticated, powerful and expensive, and worked on cracking a different and much more difficult and important German code.(nicknamed Tunny by the British). As one authority tersely concludes:

Alan Turing did not become the chief figure in the Tunny work, and in particular did not design or build the Colossus, as is often incorrectly stated. Colossus was not applied to Enigma ciphers! However, it depended on the statistical theory that Alan Turing had developed for breaking the naval Enigma.

[www.turing.org.uk/scrapbook/electronic.htm]

By 1943 the Germans were using their Enigma machines mainly for field work. But for high-level communications, including messages from Hitler and military headquarters including communication of military strategy and troop movements, the Germans were using a much more sophisticated encoding device. This used a different type of machine from Enigma: the teleprinter-based Lorenz SZ 40 and SZ 42 machines, designed by the AG Company. This was a bigger, heavier machine using fixed circuits and teleprinter mechanisms. It';s code-cracking capabilities were an incredible 5,429,503,678,976 times greater than the Enigma system. Bletchley Park had the advantage of using actual Enigma machines to help crack the Enigma code, but only after the D-Day landings did a couple of the SZ machines make their way to England. But by then the Tunny code had already been broken.

|

The credit for this feat, which enabled Bletchley to learn of the whereabouts and movements of German military formations, often attributed solely to Turing (not that he claimed it) was shared by several people and by institiutions other than Bletchley. Turing supplied crucial statistical analysis. But the real breakthrough came through the efforts of a brilliant Cambridge mathematician, Max Newman, whose German father had been interned during World War I. Newman was called upon to work at Bletchley in 1942. He insisted that the Tunny code could be broken mechanically by automated processes and began designing a machine for that task. His initial construction, built at a Bletchley hut called 'the Newmanr - was nicknamed Heath Robinson after an illustrator who drew amusing, fantastical machines - though flawed, proved that mechanisation and automation was indeed the fastest, simplest way to go. But by 1943 Newman realised that the machine he devised was too slow and inefficient to be effective. So he turned to anothe, much less glamorous institution and to a modest engineering genius.

|

That man was Thomas (Tommy) Flowers, and the institution was an essential but overlooked structure iin Britain's twentieth century communications network: the GPO [Government Post Office] Research Station located in the mundane suburban setting of Dollis Hill in Northwest London.

Flowers, born in London's working-class East End in 1905, son of a bricklayer, gained an elecctrical engineering degree whiole working as an apprentice mecanical engineer and went to work for the British GPO at the age of twenty-one. At that time the GPO ran the nation's telecommunication network. he soon moved to Dollis Hill, using electronics to make a faster, more reliable long-distance telephone system. Although he is sometimes credited with creating the world's first computer (Colossus) he admittedly that "1 was not myself interested so much in computers as in telephone exchanges."

By the start of the war Flowers was recognised as a brilliant electronics and telecommunications expert. He was a pioneer in using electronic valves in repeater stations to simplify and accelerate the whole system of making automatic phone calls over long distances. Years after the end of the war Flowers wrote that "The real origin of the Colossus machines was the work I did before the war at the Dollis Hill Research Station of the Post Office."

When assigned to design Colossus in 1943, Flowers insisted that an all-electronic process was necessary, using electronic valves to accelerate the deciphering process - an idea received skeptically by Bletchley, especially by one of its chiefs, Gordon Welchman, who, according to Max Hastings“treated him with disdain, as a mere artisan with ideas above his station”.

But accorig to Flowers "[such] riticism could be defeated by the experience of the Post Office using thousands of tubes in its communication network."

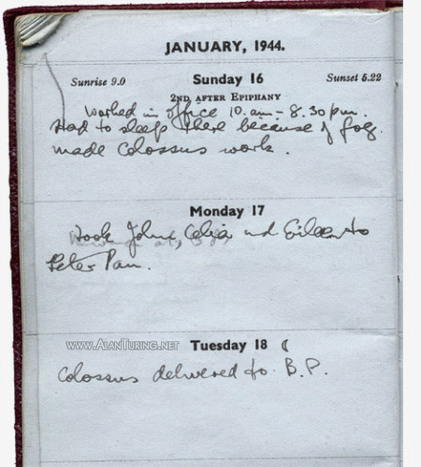

Flowers' Dollis Hill team produced the first Colossus within 11 months - " a feat made possible," he drily observed, "by the absolute priority they were given to command materials and services and the prodigious efforts of the laboratory staff, many of whom did nothing but work, eat, and sleep for weeks and months on end except for one half day per week that they allowed themselves for the necessities of life such as talking to their wives and getting their hair cut."

By D-Day Dollis Hill had delivered two of the Colossus machines to Bletchley Hill. They enabled the Allies to decipher vital German intelligence revealing that Hitler and the German High Command believed the forthcoming invasion would occur at Pas de Calais, not Normandy. They also revelaed the location and size of key German units in France and Belgium and their likely movements. The successful D-Day landings also gave Coloussus and Bletchley an enormous bonus. Allied air forces and French resistance targeted German telephine and teleprinter communications in France, forcing the Germans to rely on radio transmission of their Lorenz codes. This made interception and decipherment of the such messages easier and faster.

After D Day the French resistance and the British and American Air Forces bombed and strafed all the telephone and teleprinter land lines in Northern France, forced the Germans to use radio communications and suddenly the volume of intercepted messages went up enormously.

After the end of the war Flowers received a British Honours award of an MBE plus a thousand pounds sterling in partial compensation for spending his own money in making equipment for Colossus. His crucial role in designing and engineering Colossus remained unknown until the 1970s and then it remained overshadowed by the emerging publicity given to Turing and his team at Bletchley. Even today Flowers' amazing contribution iswidely ignored.As Max Hastings writes in his recent monumental history of espionage and coding during the conflict, The Secret War, Flowers reeceived

"a shamefully condescending recognition of his role as begetter of Colossus. Most Bletchley hands attest thathe was the practical brain who played a pivotal role in t ranslating the concepts of Turing , Newman and Wynn-Williams into reality. and indeed for advancing them to a new level of sophistication."

Quotes from "The Design of Colossus" by Thomas Flowers, article in "Boole and computer logic", Annals of the History of Computing, Volume 5, Number 3, July 1983 . p239; Max Hastings, The secret War Spies, Codes and Guerillas 1939-1945 (London, 2015), Ch.15 esp pp.415-416

Flowers, born in London's working-class East End in 1905, son of a bricklayer, gained an elecctrical engineering degree whiole working as an apprentice mecanical engineer and went to work for the British GPO at the age of twenty-one. At that time the GPO ran the nation's telecommunication network. he soon moved to Dollis Hill, using electronics to make a faster, more reliable long-distance telephone system. Although he is sometimes credited with creating the world's first computer (Colossus) he admittedly that "1 was not myself interested so much in computers as in telephone exchanges."

By the start of the war Flowers was recognised as a brilliant electronics and telecommunications expert. He was a pioneer in using electronic valves in repeater stations to simplify and accelerate the whole system of making automatic phone calls over long distances. Years after the end of the war Flowers wrote that "The real origin of the Colossus machines was the work I did before the war at the Dollis Hill Research Station of the Post Office."

When assigned to design Colossus in 1943, Flowers insisted that an all-electronic process was necessary, using electronic valves to accelerate the deciphering process - an idea received skeptically by Bletchley, especially by one of its chiefs, Gordon Welchman, who, according to Max Hastings“treated him with disdain, as a mere artisan with ideas above his station”.

But accorig to Flowers "[such] riticism could be defeated by the experience of the Post Office using thousands of tubes in its communication network."

Flowers' Dollis Hill team produced the first Colossus within 11 months - " a feat made possible," he drily observed, "by the absolute priority they were given to command materials and services and the prodigious efforts of the laboratory staff, many of whom did nothing but work, eat, and sleep for weeks and months on end except for one half day per week that they allowed themselves for the necessities of life such as talking to their wives and getting their hair cut."

By D-Day Dollis Hill had delivered two of the Colossus machines to Bletchley Hill. They enabled the Allies to decipher vital German intelligence revealing that Hitler and the German High Command believed the forthcoming invasion would occur at Pas de Calais, not Normandy. They also revelaed the location and size of key German units in France and Belgium and their likely movements. The successful D-Day landings also gave Coloussus and Bletchley an enormous bonus. Allied air forces and French resistance targeted German telephine and teleprinter communications in France, forcing the Germans to rely on radio transmission of their Lorenz codes. This made interception and decipherment of the such messages easier and faster.

After D Day the French resistance and the British and American Air Forces bombed and strafed all the telephone and teleprinter land lines in Northern France, forced the Germans to use radio communications and suddenly the volume of intercepted messages went up enormously.

After the end of the war Flowers received a British Honours award of an MBE plus a thousand pounds sterling in partial compensation for spending his own money in making equipment for Colossus. His crucial role in designing and engineering Colossus remained unknown until the 1970s and then it remained overshadowed by the emerging publicity given to Turing and his team at Bletchley. Even today Flowers' amazing contribution iswidely ignored.As Max Hastings writes in his recent monumental history of espionage and coding during the conflict, The Secret War, Flowers reeceived

"a shamefully condescending recognition of his role as begetter of Colossus. Most Bletchley hands attest thathe was the practical brain who played a pivotal role in t ranslating the concepts of Turing , Newman and Wynn-Williams into reality. and indeed for advancing them to a new level of sophistication."

Quotes from "The Design of Colossus" by Thomas Flowers, article in "Boole and computer logic", Annals of the History of Computing, Volume 5, Number 3, July 1983 . p239; Max Hastings, The secret War Spies, Codes and Guerillas 1939-1945 (London, 2015), Ch.15 esp pp.415-416