Little Big Man (1970)

Arthur Penn's Vietnam-era Revisionist Portrayal of Custer - and America

"... the angriest of all revisionist Westerns" - Elbert Ventura

"... an epic in the form of a yarn" - Roger Ebert

Little Big Man as counter-culture movie

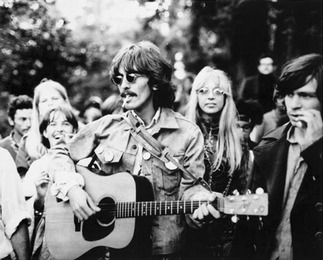

Little Big Man is a remarkable film on several levels. It is a seminal Western. It provides a thoroughly entertaining and controversial portrayal of George Armstrong Custer. It is also a bitter satire of Hollywood's decade-long portrayal of American Indians, and at the same time an indictment of white Americans' treatment of that race. As well, Little Big Man is one of those rare films that reflects and captures the spirit of its times. Made at the end of the 1960s just as the hippie era was beginning its descent into self-parody and self-righteousness, it illuminates the American countercultural phenomenon of that era. In doing so, the movie makes trenchant comments about the Vietnam war in general and the U.S. military in particular. The director's previous film, Alice's Restaurant, took a much more measured, low key approach to the subject of the war and the counter-culture. Unfortunately, its gentle, wry and ultimately rather sad outlook has resulted in it being largely ignored, although it remains the wisest of all films about the sixties culture. Compare Alice's Restaurant with Zabriskie Point: the latter's intellectual pretension and cultural glibness makes Penn's movie all the more valuable.

Strangely enough, a Disney movie Tonka / A Horse Named Comanche is a precursor of Little Big Man's revisionist attitude to Custer and the Battle of Little Big Horn'. So effective was Tonka in its attack on Custer and the U.S. military that youthful audiences of the time actually cheered the on-screen depiction of the Indians defeating the cavalry.

Signs of the Times

"... an epic in the form of a yarn" - Roger Ebert

Little Big Man as counter-culture movie

Little Big Man is a remarkable film on several levels. It is a seminal Western. It provides a thoroughly entertaining and controversial portrayal of George Armstrong Custer. It is also a bitter satire of Hollywood's decade-long portrayal of American Indians, and at the same time an indictment of white Americans' treatment of that race. As well, Little Big Man is one of those rare films that reflects and captures the spirit of its times. Made at the end of the 1960s just as the hippie era was beginning its descent into self-parody and self-righteousness, it illuminates the American countercultural phenomenon of that era. In doing so, the movie makes trenchant comments about the Vietnam war in general and the U.S. military in particular. The director's previous film, Alice's Restaurant, took a much more measured, low key approach to the subject of the war and the counter-culture. Unfortunately, its gentle, wry and ultimately rather sad outlook has resulted in it being largely ignored, although it remains the wisest of all films about the sixties culture. Compare Alice's Restaurant with Zabriskie Point: the latter's intellectual pretension and cultural glibness makes Penn's movie all the more valuable.

Strangely enough, a Disney movie Tonka / A Horse Named Comanche is a precursor of Little Big Man's revisionist attitude to Custer and the Battle of Little Big Horn'. So effective was Tonka in its attack on Custer and the U.S. military that youthful audiences of the time actually cheered the on-screen depiction of the Indians defeating the cavalry.

Signs of the Times

|

|

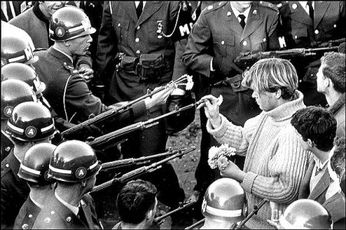

Little Big Man is one of the very few movies (director Arthur Penn's previous film, Alice's Restaurant is another) that provides lasting insights into the American counterculture of the sixties. It exemplifies several of that movement's key features. There is the contempt for the military, and for established authority and iconic American institutions and figures in the movie's portrayal of Custer and the army. His campaigns against the Indians, with their disastrous conclusion at Little Bighorn, become a metaphor for the Vietnam war. The movie's sympathetic portrayal of Indians and their culture reflects the hippie belief that a better,cleaner, more 'natural' way of life could only be found in societies uncorrupted by modern materialistic values and practices. More than four decades after its release, Little Big Man provides fascinating insights into the cultural context of the late sixties. Its treatment of Cheyenne as the only true 'human beings' - a portrayal made more telling by the magnificent performance of Chief Dan George as Old Lodge Skins. This marked the first occasion in which an Indian had a major movie role.

The Cheyenne's dignity, honor, wisdom and courage a contrast to the behaviours of the whites is naive, condescending and patronising. This is just another repeat of the old cliche of the noble savage versus the corrupt European. They are the good guys because they are supposedly in touch with nature; the corrupt Europeans have lost their way and become less than human. Various characters in the movie, such as the movie's 'hero' Jack Crabb and his sister, Custer himself, and other fictional characters such as Chief Old Lodge Skins, the l Rev, Silas Pendrake and his wife, Wild Bill Hickock etc are used to mock staple features of the conventional Hollywood western, such as the lone gunfighter, the idealized pioneer woman, the deceitful Indian, and the cavalry riding to the rescue. Infact, this is a Vietnam western. Little Big Man is a satire, and an angry one at that. As with the best satires it makes no attempt at even-handedness. |

|

Little Big Man and the Vietnam War

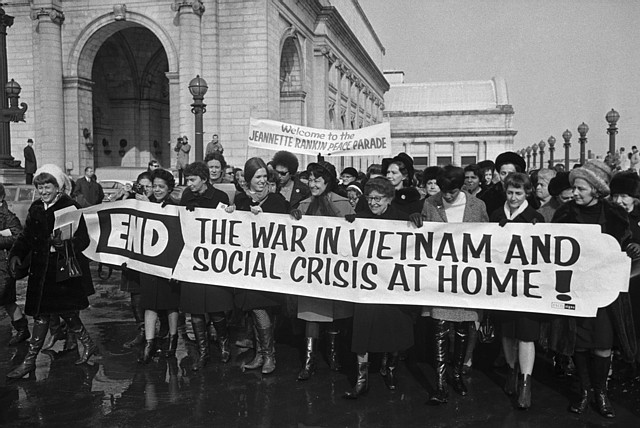

Little Big Man was released in 1970, some months after it was revealed the American military authorities had tried to cover-up a massacre carried out by their troops. In March,1968 company of soldiers from the Seventh Cavalry (the same military unit in which Custer had fought) had massacred most of the inhabitants of the South Vietname hamlet of My Lai in March 1968. As many as 500 civilians, including children, women and elderly killed. There were also incidents of rape and torture before the killings. In 1970, 14 officers were charged with crimes related to the event. Only one, Lt. William Calley, was convicted. The revelations of the massacre (and its cover-up by the military) had important consequences. Anti-war feeling increased, public support for the conflict diminished and the morale of troops in Vietnam fell even further.

The movie's release therefore came at an opportune time - for its makers, if not the U.S. military. For Little Big Man compared explicitly compared the nineteenth century military's involvement in atrocities such as the Sand Creek and Washita massacre with the twentieth century military's role in atrocities against Vietnamese civilians. And it also equated the inept leadership and military irresponsibility exhibited at Little Bighorn with its counterparts in Vietnam. The massacres of Indians by nineteenth century American soldiers translates in the movie to the American massacres of Vietnamese in the twentieth century.

Little Big Man was released in 1970, some months after it was revealed the American military authorities had tried to cover-up a massacre carried out by their troops. In March,1968 company of soldiers from the Seventh Cavalry (the same military unit in which Custer had fought) had massacred most of the inhabitants of the South Vietname hamlet of My Lai in March 1968. As many as 500 civilians, including children, women and elderly killed. There were also incidents of rape and torture before the killings. In 1970, 14 officers were charged with crimes related to the event. Only one, Lt. William Calley, was convicted. The revelations of the massacre (and its cover-up by the military) had important consequences. Anti-war feeling increased, public support for the conflict diminished and the morale of troops in Vietnam fell even further.

The movie's release therefore came at an opportune time - for its makers, if not the U.S. military. For Little Big Man compared explicitly compared the nineteenth century military's involvement in atrocities such as the Sand Creek and Washita massacre with the twentieth century military's role in atrocities against Vietnamese civilians. And it also equated the inept leadership and military irresponsibility exhibited at Little Bighorn with its counterparts in Vietnam. The massacres of Indians by nineteenth century American soldiers translates in the movie to the American massacres of Vietnamese in the twentieth century.

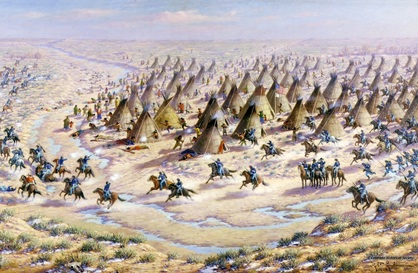

Two key sequences in Little Big Man show units of the U.S. army carrying out massacres of Indian civilians. The first is the Sand Creek massacre of 1864, where 148 Cheyenne and Arapahoe Indians ( the majority were women and children) were killed by U.S. Army Colonel John Chivington's Colorado Volunteers. The Indians were there at the urging of a local commander and supposedly protected by a recent peace treaty. Chivington's troops killed wounded. mutilated bodies and burnt the Indian village. Custer was not involved -he was fighting in the civil war.

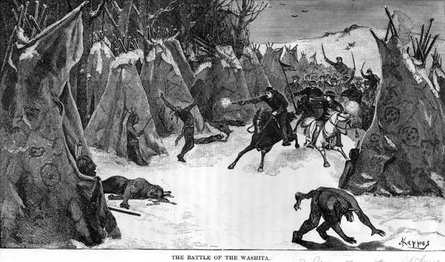

The second movie sequence shows the Washita massacre of 1868. This time Custer was fully involved. General Philip Sheridan had recently reinstated Custer after the latter had been suspended from duty for a year after his conviction for desertion and mistreatment of soldiers. But Sheridan wanted a fighter who would track down some Cheyenne raiders who had eluded his units for months. In late November Custer found a large Cheyenne winter camp by the Washita river in Oklahoma. In fact, this was one of their reservation sites, and the Indians' safety had been guaranteed by the local commander. Custer made no attempt to confirm the identity of this group of Cheyenne. Instead he surrounded the camp and immediately attacked it with his soldiers. Over a hundred Cheyenne - again, many of them women and children - were killed.

The Washita massacre sequence in Little Big Man is magnificent but harrowing cinema. The intensity and pathos of the atrocity is cleverly emphasised by the way Penn sets up the scene by focusing on the magnificent wintry setting of the Indian camp, its obviously peaceful purpose and the domesticity of the birth of Jack Crab's child just before Custer's forces move in. The John Ford-like long shots of the Cavalry advancing on the slumbering village to the regimental tune of "Garry Owen" have a grandeur that contrasts with the brutalities that follow.

The second movie sequence shows the Washita massacre of 1868. This time Custer was fully involved. General Philip Sheridan had recently reinstated Custer after the latter had been suspended from duty for a year after his conviction for desertion and mistreatment of soldiers. But Sheridan wanted a fighter who would track down some Cheyenne raiders who had eluded his units for months. In late November Custer found a large Cheyenne winter camp by the Washita river in Oklahoma. In fact, this was one of their reservation sites, and the Indians' safety had been guaranteed by the local commander. Custer made no attempt to confirm the identity of this group of Cheyenne. Instead he surrounded the camp and immediately attacked it with his soldiers. Over a hundred Cheyenne - again, many of them women and children - were killed.

The Washita massacre sequence in Little Big Man is magnificent but harrowing cinema. The intensity and pathos of the atrocity is cleverly emphasised by the way Penn sets up the scene by focusing on the magnificent wintry setting of the Indian camp, its obviously peaceful purpose and the domesticity of the birth of Jack Crab's child just before Custer's forces move in. The John Ford-like long shots of the Cavalry advancing on the slumbering village to the regimental tune of "Garry Owen" have a grandeur that contrasts with the brutalities that follow.

The Movie's Portrayal of Custer

Little Big Man 's depiction of George Armstrong Custer is quite deliberately the opposite of the portrayal that we see in They Died With Their Boots On. That movie's romanticised picture of Custer, so dashingly provided by Errol Flynn, has been turned on its head. However, it owes something to the portrayal of Custer in - surprisingly - a Disney movie, Tonka, which presents him as a distinctly arrogant, foolish and bloodthirsty man.

Penn's movie makes no pretence at being even-handed. It is above all a satire, and Custer is seen through the fictional and unfavorable perspective of the film's (anti) hero and narrator, Jack Crabb, who cliams to be the sole white survivor of Little Bighorn.. "I knowed George Armstrong Custer for what he was," claims Crabb, and the movie shows Custer (Richard Mulligan) through the distorted and satiric perspective of Crab's various encounters with the General. So when Jack, with wife Olga first meet Custer he advises the pair to go West. "You have nothing to fear from the Indians. I give you my personal guarantee." Cut to a group of Indians cheerfully kidnaping Olga. As the encounters with Custer accumulate, he is seen as an impatient and arrogant braggart despised by his soldiers. He is also revealed as an ambitious warmonger, paranoid to the point of eventual insanity, contemptuous of advice.

That insanity erupts at Little Bighorn. Whereas the traditional image of Custer at that battle paints a picture of a proud, calm, defiant hero resisting the enemy to the last, Little Big Man's Custer is shown as a selfish egoist, desperate and despairing, ignoring his soldiers, absolving himself of blame, hysterically wandering about the battlefield in a hallucinatory haze berating Congress and the President.

Little Big Man 's depiction of George Armstrong Custer is quite deliberately the opposite of the portrayal that we see in They Died With Their Boots On. That movie's romanticised picture of Custer, so dashingly provided by Errol Flynn, has been turned on its head. However, it owes something to the portrayal of Custer in - surprisingly - a Disney movie, Tonka, which presents him as a distinctly arrogant, foolish and bloodthirsty man.

Penn's movie makes no pretence at being even-handed. It is above all a satire, and Custer is seen through the fictional and unfavorable perspective of the film's (anti) hero and narrator, Jack Crabb, who cliams to be the sole white survivor of Little Bighorn.. "I knowed George Armstrong Custer for what he was," claims Crabb, and the movie shows Custer (Richard Mulligan) through the distorted and satiric perspective of Crab's various encounters with the General. So when Jack, with wife Olga first meet Custer he advises the pair to go West. "You have nothing to fear from the Indians. I give you my personal guarantee." Cut to a group of Indians cheerfully kidnaping Olga. As the encounters with Custer accumulate, he is seen as an impatient and arrogant braggart despised by his soldiers. He is also revealed as an ambitious warmonger, paranoid to the point of eventual insanity, contemptuous of advice.

That insanity erupts at Little Bighorn. Whereas the traditional image of Custer at that battle paints a picture of a proud, calm, defiant hero resisting the enemy to the last, Little Big Man's Custer is shown as a selfish egoist, desperate and despairing, ignoring his soldiers, absolving himself of blame, hysterically wandering about the battlefield in a hallucinatory haze berating Congress and the President.