Stalin and the Movies:

The tyrant as film buff

Stalin's attitude to movies: background

|

"Of all the arts, the cinema for us is the most important" - Lenin

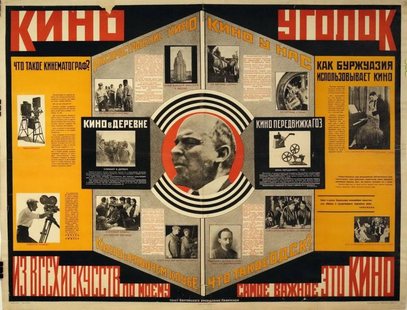

Andrei Konchalovsky's movie The Inner Circle accurately depicts Stalin as a film buff. Most historians assume that Stalin's interest in movies was based on Lenin's dictum. However, Lenin held ambiguous views on cinema. His famous statement was "not an artistic but a functional judgement" . That is, Lenin regarded the cinema in terms of its effectiveness as a means of visual propaganda that would immediately appeal to the largely illiterate mass of Russia's population. The fact that the cinema of the era was visual and silent (in the immediate post-revolution decade) also meant that it overcame the huge communications problem posed by Russia'shuge range of languages and cultures. It also had the advantages -for many Communist intellectuals - of being both mechanical and modern, an appropriate art form for the machine age. But while Lenin approved of movies for their educational/ propaganda potential and as an instrument of social and political change, he also had a more pragmatic attitude to the medium. They provided entertainment and distractionfor the millions of Russians who suffered from low income, bad working conditions, insufficent food, a clumsy and intrusive bureacracy,and the perils of a rapidly-growing police state. And popular movies (i.e. Hollywood films) provided box-office income for the State. So in 1922 Lenin issued |

|

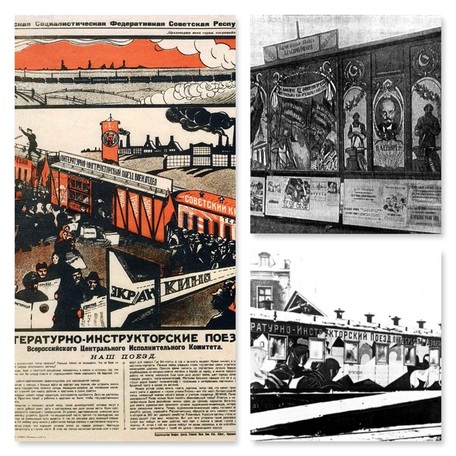

Left: After the 1917 revolution, throughout the civil war that followed and for most of the 1920s, Soviet authorities used 'agit-trains' to spread Communist-governement propaganda throughout what became the USSR. AS well as displays, posters and exhibits, many contained wagons fitted out to show movies. Most were documentaries on such subjects as combatting head-lice, basic hygiene, the need for literacy. Others declaimed the virtues of Soviet leaders and the Bolshevik government, and attacked so-called 'exploiters of the masses' e.g. "rich" peasants. Some of the cinema gait-trains had facilities not only to project movies, but also carried equipment to film, process and edit them on the spot.

|

|

Is the movie accurate in its depiction of secret police chief Beria?

In the movie the figure of secret police chief Laventri Beria (Bob Hoskins) serves as the embodiment of Stalin's tyrannical rule. Hoskins' portrayal of Beria as a devious, opportunistic, bullying politician and a vicious sexual predator (and a contrast to the movie's apparently warmer, subtler Stalin) has been supported in recent years by the release of previously concealed documentary evidence. Beria (as Stalin and his ministers knew) was a truly monstrous figure - a serial rapist, torturer and murderer, who had his victims' bodies buried in the cellars of his Moscow house. Parts of their skeletons and grisly evidence of their deaths have been found. The Inner Circle was accurate in suggesting that Beria was a crucial figure in Stalin's government. "Our Himmler" Stalin described him to President Roosevelt at Yalta in 1945. LIke Stalin, Beria was born in Georgia and took part in Georgian revolutionary activities,although apparently he and Stalin did not meet until 1932. Stalin enjoyed talking to him in the distinctive Georgian language. He became head of CHEKA (the Bolshevik secret police) and by the mid-1930s had ruthlessly made his way up the ranks of the Cheka's successors, ending up in 1939 as head of the NKVD. Beria was a brilliantly efficient administrator of the terror and espionage network. He supervised Stalin's late 1930s purge of the armed forces [at least 30 000 Red Army officers killed], the NKVD itself and the establishment of the slave labor camps [the Gulag] in which millions of Russians were sent. He also supervised Russia's atomic bomb project. A sign of his favored position in the inner circle was that he sat in the front row of the Kremlin Palace cinema for Stalin;s regular movie showings. After Stalin's death in 1953 Beria was an incredibly powerful figure: deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Internal Affairs i.e. in charge of both the secret police and regular police. But in July, 1953, some of his colleagues, realising he intended to grab absolute power, had him arrested, stripped of his posts and charged with high treason (spying for Britain!) He was executed, possibly that month or in December. |

Did many Russians really share the movie anti-hero's idealisation of Stalin?

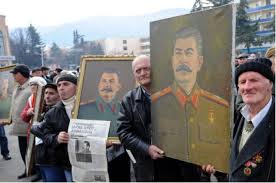

Posters glorifying Stalin (clockwise, from top right): Stalin as the great helmsman; Stalin as staunch defender of the Motherland; as leader of the masses of the world's masses; early 21st century admirer with poster of Stalin in religious icon pose; and Stalin as strategic genius. The movie controversially argues that Stalin and his dictatorship was willingly accepted and condoned by ordinary Russians who, like the projectionist anti-hero, idealise their leader.

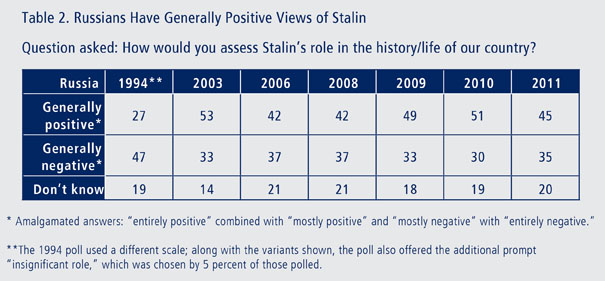

Decades later, and years after the publication of details verifying the horrifying details of Stalin's totalitarian rule and its consequences, a significant section of the Russian population still approved of Stalin. A 2011 survey [below] found that 45% of Russians regarded Stalin as a positive force in Russian history, while only 35% viewed him as a negative force.

Decades later, and years after the publication of details verifying the horrifying details of Stalin's totalitarian rule and its consequences, a significant section of the Russian population still approved of Stalin. A 2011 survey [below] found that 45% of Russians regarded Stalin as a positive force in Russian history, while only 35% viewed him as a negative force.

Stalin and Hollywood

|

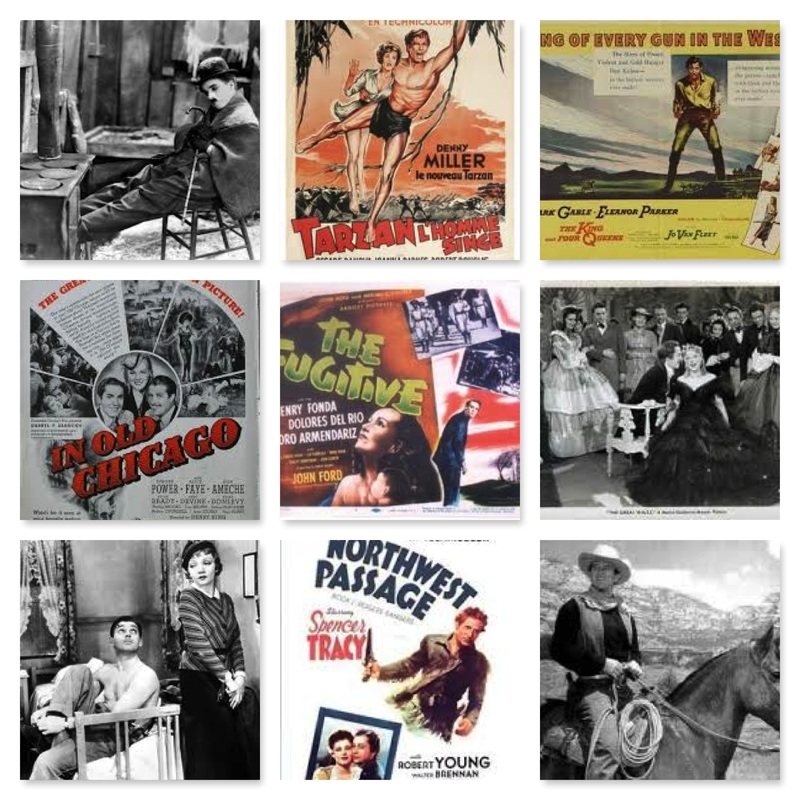

Hollywood movies and movie genres that Stalin enjoyed watching

|

and public intellectualsFor a communist, Hollywood exemplified both American capitalism and bourgeois culture at their worst. American films were regarded by communist intellectuals in both the USSR and the west as degenerate soporifics which dulled the revolutionary edge of the masses and which encouraged unthinking mass consumption of capitalist goods. Yet during the interwar years Russians flocked to see those Hollywood movies that the Communist regime permitted. Audiences for Thief of Bagdad, for example, far outnumbered those for The Battleship Potemkim.

Stalin shared this enthusiasm for Hollywood movies. However, only Stalin and his inner circle were able to watch such movies; after 1931 foreign movies were not allowed to be shown in the USSR. We now know that he loved Charlie Chaplin movies -except for The Great Dictator - and the Tarzan series, as well as films starring James Cagney. Romantic musicals like The Great Waltz (1938) met with his approval. In Old Chicago and It Happened One Night were favorites. Director John Ford's movies also met with Stalin's approval -the dictator admired the western genre. Nikita Khruschev claimed that Stalin would condemn the ideology of westerns, and then order more. Stalin was also a great fan of John Wayne, that embodiment of American rugged individualism and anti-communism. (Although he may have once suggested that Wayne should be assassinated, according to Khruschev). Gangster films were another of Stalin's favored movie genres, especially ones showing criminals killing their rival. See Simon Sebag-Montefiore's article "Why Stalin Loved Tarzan...." |

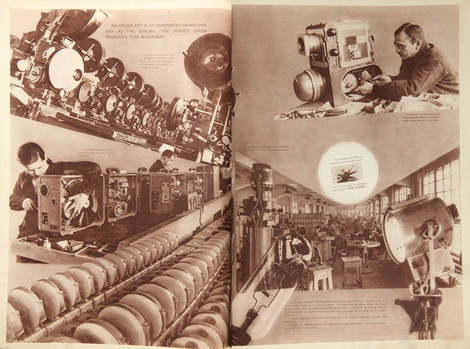

Stalin and Soviet Cinema

their Stalin's interest in movies was not limited to regular screenings of Hollywood films. He also actively supervised Soviet cinema for three decades. During this time Stalin not acted as the ultimate censor, ordering films to be cut, remade or banned - even destroyed. His control of Soviet movie-making was incredibly detailed. He "suggested" subjects and genres, directors, actors, writers and composers. The dictator read scripts of proposed Soviet movies(and scribbled notes on them), watched rough cuts, demanded insertion or deletion of scenes and dialogue, and demanded promotion, demotion or 'removal' of writers, directors and others who had committed various artistic or ideological sins.

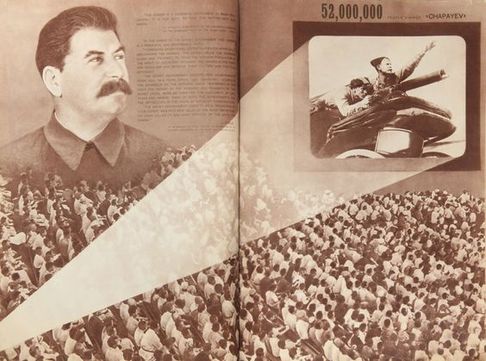

The historian Stephen Kotkin believes that a key moment in the dictator's attitude towards cinema came in 1934, when he was shown a preview of a new Soviet movie, Chapayev, [Chapaev] about Reds and Whites in the civil war. Stalin loved the movie. He ordered the Kremlin mouthpiece Pravda to print a rave review, Kotkin maintains that the movie transformed Stalin from someone “who occasionally viewed films for diversion to their executive producer, from, from the backgrounds of scenes to the dialogue and score. The dictator played a decisive role in in supporting not just subjects of political import but also farces. [Stephen Krotkin, Stalin: Waiting for Hitler,1929 - 1941. In fact, Stalin went on the watch Chapayev at least another 36 times. (New York, 2017) p.215 -216;285

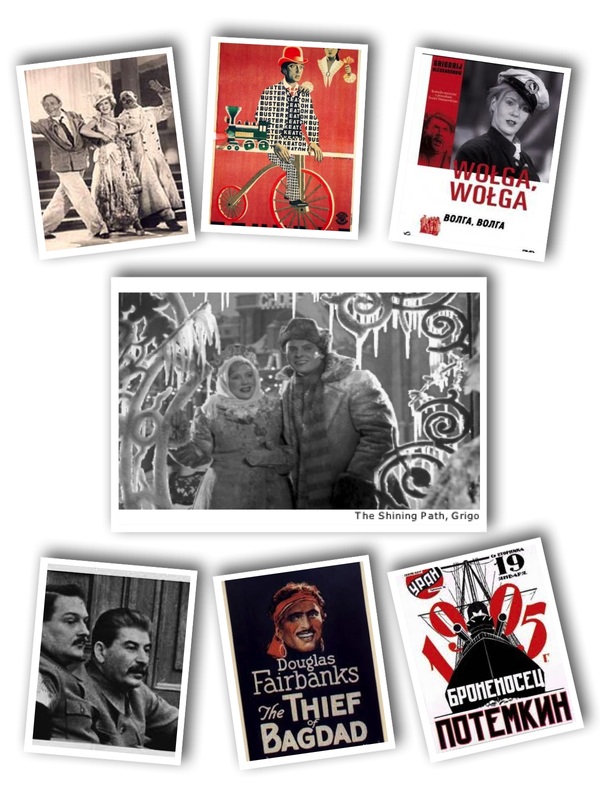

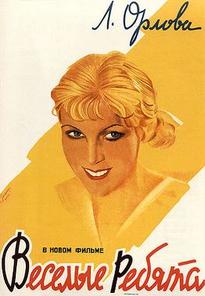

Despite official Communist condemnation and mockery of Hollywood (endorsed for decades in Western nations by their cultural guardians and public intellectuals, [see Campaign Against Hollywood] Stalin enjoyed Hollywood genre movies, westerns, action films and especially musical comedies. But these movies were available only for the Communist elite, not for ordinary Russians. Thus a 1930s Russian movie Jolly Fellows was highly praised by Stalin, although it was a rip-off of a typical Hollywood musical-comedy features of that era: unknown talent struggles against adversity to reach showbiz big-time, mix of cheerful and sentimental songs, some jazz, Busby Berkeley style production. Stalin kept a close on on Jolly Fellows production and had the final say in its final edit and demanded a huge Hollywood style publicity campaign. .

Stalin's control of Russian movie-making was disastrous for that nation's cinematic prowess. In the 1920s the Communist government allowed Hollywood movies to be shown; stars like Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks Jr were tremendously popular with Russian audiences and their films easily outsold the sombre and didactic Russian films of that era.

The historian Stephen Kotkin believes that a key moment in the dictator's attitude towards cinema came in 1934, when he was shown a preview of a new Soviet movie, Chapayev, [Chapaev] about Reds and Whites in the civil war. Stalin loved the movie. He ordered the Kremlin mouthpiece Pravda to print a rave review, Kotkin maintains that the movie transformed Stalin from someone “who occasionally viewed films for diversion to their executive producer, from, from the backgrounds of scenes to the dialogue and score. The dictator played a decisive role in in supporting not just subjects of political import but also farces. [Stephen Krotkin, Stalin: Waiting for Hitler,1929 - 1941. In fact, Stalin went on the watch Chapayev at least another 36 times. (New York, 2017) p.215 -216;285

Despite official Communist condemnation and mockery of Hollywood (endorsed for decades in Western nations by their cultural guardians and public intellectuals, [see Campaign Against Hollywood] Stalin enjoyed Hollywood genre movies, westerns, action films and especially musical comedies. But these movies were available only for the Communist elite, not for ordinary Russians. Thus a 1930s Russian movie Jolly Fellows was highly praised by Stalin, although it was a rip-off of a typical Hollywood musical-comedy features of that era: unknown talent struggles against adversity to reach showbiz big-time, mix of cheerful and sentimental songs, some jazz, Busby Berkeley style production. Stalin kept a close on on Jolly Fellows production and had the final say in its final edit and demanded a huge Hollywood style publicity campaign. .

Stalin's control of Russian movie-making was disastrous for that nation's cinematic prowess. In the 1920s the Communist government allowed Hollywood movies to be shown; stars like Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks Jr were tremendously popular with Russian audiences and their films easily outsold the sombre and didactic Russian films of that era.

|

At the same time Russian cinema produced some of the most stunning artistically advanced movies of the silent era. Some Russian directors of that era - Eisenstein, Dovzhenko - are regarded as cinematic masters. And many Russian films of the 1920s are now regarded as classics: Battleship Potemkin, Strike.

But by the early 1930s Stalin had consolidated his power and Soviet cinema plunged into a downward spiral of censorship, ideological constraints and bureaucratic ineptitude, all occurring within an atmosphere of fear and suspicion. The Communist Party exercised tight control over all forms of culture. A centralised bureaucracy, Soyuzkino, controlled the production, content, distribution and exhibition of movies. And for all the Party's ideological disapproval of 'frivolous' 'decadent', bourgeois-capitalist Hollywood films, under Stalin, Soyuzkino favored the very genres of musical comedy and melodrama beloved of Hollywood studios. The approved Soviet movie style (labelled "cinema for the millions") also copied the Hollywood style of clear linear narrative involving moral uplift. The director Gregori Aleksandrov (who was one of Eisenstein's lovers and advisers) was famous for his musical-comedies, which usually featured his comedienne--dancer wife Lyubov Orlova, who was immensely popular for decades and was lavished with plaudits and rewards by Stalin. These included Volga-Volga (1938) and The Shining Path. Stalin and his cultural commissar Zhdanov (Collage:with Stalin, bottom left) made sure that Russian film-makers conformed to his standards of taste and style. Great innovators like Eisenstein (Battleship Potemkin) languished while cheerful musical comedies such as Jolly Fellows,Shining Path and Volga-Volga flourished. Buster Keaton. the Marx Brothers and Douglas Fairbanks movies, all favorites of Stalin's personal viewing , went unseen by Russian audiences after 1931. |

Stalin and Eisenstein

Eisenstein at work.

Eisenstein at work.

Stalin's treatment of the legendary Russian director Sergei Eisenstein, one of the seminal movie makers of the twentieth century, reveals the extent to which the dictator exerted control over Soviet movie-making, and the fear in which he was held by Russia's intelligentsia.

During the 1920s the young Eisenstein had established himself as one of the world's most innovative and profound directors, with such films as Battleship Potemkin, Strike, and Ten Days That Shook the World. But by the late Eisenstein's avant-garde techniques and idiosyncratic choice of subject-matter had aroused the anger of Stalin and the Communist cultural commissars, who insisted he and other film-makers conform to the official, unadventurous 'socialist realism' demanded by the Party and to a narrow range of approved topics.

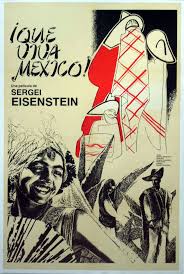

During the early 1930s Eisenstein spent some time in western countries and shot considerable footage in Mexico for monumental film intended to be called Que viva Mexico! and financed with Hollywood money. But the project was never completed and Stalin let it be known that he was displeased with Einstein's 'desertion' from Russia - a serious accusation in an era of unremitting purges of party, artists and army. When Eisenstein returned to Russia, Stalin eventually offered him 'a last chance' - to make an epic biopic about the medieval Russian hero Alexander Nevsky who fought off German invaders.

Alexander Nevsky [1938] - Eisenstein's first movie with sound (and music by Prokofiev) - was immeditely praised as masterpiece both in Russia and the West. But mohts later Stalin signed the Nazi-Soviet Pact and the film was withdrawn in Russia. However the 1941 Nazi invasion of Russia meant that it returned to cinemas and Stalin approved Eisenstein's plan to make a movie about the 16rth Century Tsar Ivan IV, the tyrannical 'Ivan the Terrible" whom Stalin admired. Intended to be a trilogy, Stalin loved Part 1 [released 1944] but he realised that Part II [1946] was a vicious mockery of his hero and so the film was suppressed and all work on Part III was halted, never to resume. The director was forced to agree to a list of "ideological errors" made nby his film, including the charge that Ivan was made to look weak-willed and vicillating instead of strong and the Tsar's 'enforcers' [oprichniki] were portrayed as a gang of thugs instead of as loyal Russins ridding the state of class enemies. Eisenstein died a couple of years later.

The opening of Soviet cultural archives has revealed fascinating evidence about Stalin's attitude to movies and his edicts on what type of film he wanted. One valuable document records a meeting which included Stalin and Esenstein over Part 2 of Ivan.

During the 1920s the young Eisenstein had established himself as one of the world's most innovative and profound directors, with such films as Battleship Potemkin, Strike, and Ten Days That Shook the World. But by the late Eisenstein's avant-garde techniques and idiosyncratic choice of subject-matter had aroused the anger of Stalin and the Communist cultural commissars, who insisted he and other film-makers conform to the official, unadventurous 'socialist realism' demanded by the Party and to a narrow range of approved topics.

During the early 1930s Eisenstein spent some time in western countries and shot considerable footage in Mexico for monumental film intended to be called Que viva Mexico! and financed with Hollywood money. But the project was never completed and Stalin let it be known that he was displeased with Einstein's 'desertion' from Russia - a serious accusation in an era of unremitting purges of party, artists and army. When Eisenstein returned to Russia, Stalin eventually offered him 'a last chance' - to make an epic biopic about the medieval Russian hero Alexander Nevsky who fought off German invaders.

Alexander Nevsky [1938] - Eisenstein's first movie with sound (and music by Prokofiev) - was immeditely praised as masterpiece both in Russia and the West. But mohts later Stalin signed the Nazi-Soviet Pact and the film was withdrawn in Russia. However the 1941 Nazi invasion of Russia meant that it returned to cinemas and Stalin approved Eisenstein's plan to make a movie about the 16rth Century Tsar Ivan IV, the tyrannical 'Ivan the Terrible" whom Stalin admired. Intended to be a trilogy, Stalin loved Part 1 [released 1944] but he realised that Part II [1946] was a vicious mockery of his hero and so the film was suppressed and all work on Part III was halted, never to resume. The director was forced to agree to a list of "ideological errors" made nby his film, including the charge that Ivan was made to look weak-willed and vicillating instead of strong and the Tsar's 'enforcers' [oprichniki] were portrayed as a gang of thugs instead of as loyal Russins ridding the state of class enemies. Eisenstein died a couple of years later.

The opening of Soviet cultural archives has revealed fascinating evidence about Stalin's attitude to movies and his edicts on what type of film he wanted. One valuable document records a meeting which included Stalin and Esenstein over Part 2 of Ivan.

Below left: the iconic baby carriage sequence from Potemkin; right: Brian de Palma trumps Eisenstein in his tribute to the sequence (The Untouchables)

|

|

|