1941

Part 2: Steven Spielberg & the Making of the Movie

"Comedy is not my forte"

Even before 1941 was released to a critical mauling in 1979, Steven Spielberg realized that it would receive an adverse reception amongst audiences and critics. He described it as "a real risk for me." Much of this risk came from the director's intention to make a film that was rather different in tone, style, content and production from his previous movies, which had achieved widespread critical and commercial success. The plot focused on no fewer than seven stories colliding with each other " a nuclear reaction". As Spielberg commented, this marked a distinct break from "the linear story form that I'm used to working with." He was quick to point out a problem associated with having seven interacting plots. Their multiple introductions and scene-settings meant that the film suffered from what he called "erratic pacing". The director claimed that the pacing consequently slowed the movie down for "25 minutes ... those miserable 25 minutes," which made the test audiences "a little antsy". He also worried that the movie "may be too intense for some people" and expressed his hope / doubt that there were sufficient "abnormal crazies in the world" to make 1941 profitable.

(All Spielberg quotes this page from 'Directing 1941', American Cinematographer, December 1979 p.1212+)

(All Spielberg quotes this page from 'Directing 1941', American Cinematographer, December 1979 p.1212+)

What type of movie did Spielberg intend 1941 to be?

Spielberg wanted to make his first comedy

He had a distinct vision for 1941. "I had always wanted to try a visual comedy, but with enough action and adventure where I felt I'd sort of be in my own element and not out in the cold, though there is nothing harder than getting an audience to laugh. getting an audience to scream at a shark or getting an audience to cry at the awesome wonders of outer space and some sort of terrestrial rival is nothing compared to getting 800 people per screening to laugh out loud at something you think is funny." He chose a politically-incorrect script by young, aspiring film-makers Robert Zemickis and Bob Gale, previously accepted by director John Milius, as the vehicle for the raucous and spectacular comedy /action film he had in mind.

He wanted to make a distinctive type type of comedy

Not only did Spielberg want to focus on the visual aspect of movie comedy, he wanted it to have a distinctive edge. He was seeking what he called "a kind of surrealism, a comedy surrealism." The controversial aspects of 1941 display this feature: the visual mayhem, the delight in physical destruction, the revealing in confusion, the complicated interaction of disparate characters and plot lines, the sardonic and often disparaging attitude towards people and events.

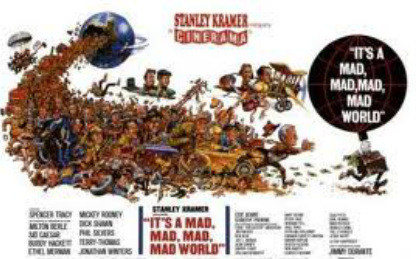

Spielberg admitted to being influenced by three Hollywood comedies in particular. The most important of these was the 1941 musical Hellzapoppin! with its emphasis on zany situations and unsettling visuals. Hellzapoppin's frequently dark juxtaposition of comedy and horror elements remain unsettling even today. Another comedy whose influence the director acknowledged was Stanley Kramer's comic extravaganza It's a Mad, Mad, Mad Mad World which had almost fifty co-stars, an incoherent plot and visual mayhem and a heavy reliance on slapstick. Spielberg lists his third influence as The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming, a gentler and subtler 1966 comedy set in a small coastal New England town whose inhabitants mistake the accidental grounding of a Russian submarine for an invasion. Its mild, ironic mood and tolerant comment on war, prejudice and young love is far removed from the tone of Hellzapoppin', Mad World and 1941 itself. However, the The Russians Are Coming's theme of how Americans reacted to an 'invasion' was absolutely crucial to 1941.

He had a distinct vision for 1941. "I had always wanted to try a visual comedy, but with enough action and adventure where I felt I'd sort of be in my own element and not out in the cold, though there is nothing harder than getting an audience to laugh. getting an audience to scream at a shark or getting an audience to cry at the awesome wonders of outer space and some sort of terrestrial rival is nothing compared to getting 800 people per screening to laugh out loud at something you think is funny." He chose a politically-incorrect script by young, aspiring film-makers Robert Zemickis and Bob Gale, previously accepted by director John Milius, as the vehicle for the raucous and spectacular comedy /action film he had in mind.

He wanted to make a distinctive type type of comedy

Not only did Spielberg want to focus on the visual aspect of movie comedy, he wanted it to have a distinctive edge. He was seeking what he called "a kind of surrealism, a comedy surrealism." The controversial aspects of 1941 display this feature: the visual mayhem, the delight in physical destruction, the revealing in confusion, the complicated interaction of disparate characters and plot lines, the sardonic and often disparaging attitude towards people and events.

Spielberg admitted to being influenced by three Hollywood comedies in particular. The most important of these was the 1941 musical Hellzapoppin! with its emphasis on zany situations and unsettling visuals. Hellzapoppin's frequently dark juxtaposition of comedy and horror elements remain unsettling even today. Another comedy whose influence the director acknowledged was Stanley Kramer's comic extravaganza It's a Mad, Mad, Mad Mad World which had almost fifty co-stars, an incoherent plot and visual mayhem and a heavy reliance on slapstick. Spielberg lists his third influence as The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming, a gentler and subtler 1966 comedy set in a small coastal New England town whose inhabitants mistake the accidental grounding of a Russian submarine for an invasion. Its mild, ironic mood and tolerant comment on war, prejudice and young love is far removed from the tone of Hellzapoppin', Mad World and 1941 itself. However, the The Russians Are Coming's theme of how Americans reacted to an 'invasion' was absolutely crucial to 1941.

|

|

|

Spielberg claims he wanted to experience working in big studio conditions as in Hollywood's 'Golden Era'

The young director admitted that he sought to make what he called "a studio movie as in the past" - that is, filming almost entirely within the confines of a studio, and relying heavily on technical expertise and state of the art facilities, while dispensing with location shooting. 1941 gave him "my first taste of what it was like to shoot a real Hollywood movie....often 'd say to myself 'Yeah, this is wheat John Fords and Raoul Walsh did every day.' There was a lot of studio shooting in those days and there's a real feeling of 'Hey, I'm in showbiz!' as opposed to being out in the middle of the Rocky Mountains when a storm blows up ....There is a real sense of the old-time Tinseltown on a Hollywood sound stage.'

This is a puzzling claim. Spielberg's previous movie, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, could not have been made without the financial and technical support of two major studios - Universal and Columbia. The logistical and technological demands of the film were such that most of it had to be filmed in sound stages; indeed, Universal built a cavernous sound stage in order to ensure that many key scenes could be filmed. And Close Encounters relied heavily on the model-constructing, photographic and special effects expertise of many studio personnel. So 1941 was hardly the director's "first taste" of working in big studio conditions.

Did Spielberg use 1941 to test his ability to make a sustained musical/dance sequence?

The young director admitted that he sought to make what he called "a studio movie as in the past" - that is, filming almost entirely within the confines of a studio, and relying heavily on technical expertise and state of the art facilities, while dispensing with location shooting. 1941 gave him "my first taste of what it was like to shoot a real Hollywood movie....often 'd say to myself 'Yeah, this is wheat John Fords and Raoul Walsh did every day.' There was a lot of studio shooting in those days and there's a real feeling of 'Hey, I'm in showbiz!' as opposed to being out in the middle of the Rocky Mountains when a storm blows up ....There is a real sense of the old-time Tinseltown on a Hollywood sound stage.'

This is a puzzling claim. Spielberg's previous movie, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, could not have been made without the financial and technical support of two major studios - Universal and Columbia. The logistical and technological demands of the film were such that most of it had to be filmed in sound stages; indeed, Universal built a cavernous sound stage in order to ensure that many key scenes could be filmed. And Close Encounters relied heavily on the model-constructing, photographic and special effects expertise of many studio personnel. So 1941 was hardly the director's "first taste" of working in big studio conditions.

Did Spielberg use 1941 to test his ability to make a sustained musical/dance sequence?

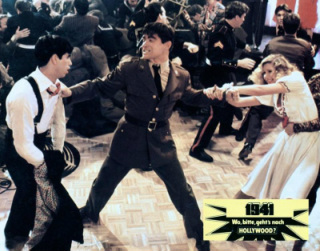

Even the severest critics of 1941 usually exempt the sustained USO swing dance sequence in 1941. Not only does this sequence have the crucial functions of bringing together four of the key characters and two separate plot-lines, as well as providing a rationale for the consequent riot between the navy and army personnel. It is also one of the best movie depictions of swing dancing, and an exuberant display of cinematic technique. The kaleidoscopic patterns of colors and the agility of the dancers along with the beat of the swing orchestra are all captured by Spielberg.

During the war Hollywood made several films that incorporated swing music and swing dancing into their plots. These included Hellzapoppin, which included two such sequences, the most famous being the Lindy Hop routine by Whitey's Lindy Hoppers. One of these was a war movie, The Fighting Seabees. Others included Four Jills and a Jeep and Hollywood Canteen. Sometimes the setting for these swing sequences - as in 1941 - was a USO -organized dance or concert.

Although the jitterbug competition provided Spielberg with the opportunity to exploit the graceful maneuverability of the new Louma camera crane system, he may also have seen the sequence as a chance to try his hand at the genre of dance musicals without actually having to make a movie musical. "In the back of my mind", he later explained, "I always saw 1941 as an old-fashioned Hollywood musical...I just didn't have the courage at that time in my life to tackle a musical." [Joseph McBride, Steven Spielberg a Biography , 2nd ed. 2010], p.305]

During the war Hollywood made several films that incorporated swing music and swing dancing into their plots. These included Hellzapoppin, which included two such sequences, the most famous being the Lindy Hop routine by Whitey's Lindy Hoppers. One of these was a war movie, The Fighting Seabees. Others included Four Jills and a Jeep and Hollywood Canteen. Sometimes the setting for these swing sequences - as in 1941 - was a USO -organized dance or concert.

Although the jitterbug competition provided Spielberg with the opportunity to exploit the graceful maneuverability of the new Louma camera crane system, he may also have seen the sequence as a chance to try his hand at the genre of dance musicals without actually having to make a movie musical. "In the back of my mind", he later explained, "I always saw 1941 as an old-fashioned Hollywood musical...I just didn't have the courage at that time in my life to tackle a musical." [Joseph McBride, Steven Spielberg a Biography , 2nd ed. 2010], p.305]

|

The director wanted to exploit the exciting capabilities of a new type of movie camera

1941's complicated action and dance sequences shot in the confines of sound-stages offered Spielberg the perfect opportunity to exploit the virtuosity of a new type of video-monitored movie camera. This was the Louma crane camera, recently invented by two Frenchmen, Jean-Marie Lavalou and Alain Maseron during their military service in order to make a training film inside a submarine. Both inventors were present at times on the set of 1941. Spielberg may well have been impressed by its use in the 1982 Italian horror film Tenebrae (Dir: Dario Argento), which featured a complicated two and a half minute tracking shot along, up and over a building. Spielberg said that he was "really amazed at its versatility and how it could get you where no camera or operator could go before. I had originally only planned to use it for the mockup shots simulation of flight and for the big dance number....But when it arrived ...I thought, 'Hey, this great! I can shoot a closeup and them just swing the arm around and and do an over-the-shoulder shot without moving the dolly, without nailing down the tripod, without changing too much." Spielberg also fell in love with another feature of the Louma camera, an aspect that did not enthrall camera operators or cinematographers (William Fraker,1941's cinematographer "hated" it). The director could use the video monitor to operate the camera himself, in effect making decisions previously left to the camera operator/cinematographer. Consequently, Spielberg admitted that he made the Louma his "'A' camera" from then on - "I could fish for the right shot by looking at the monitor and could get just the shot I wanted...." Citations from American Cinematographer , December 1979,' Photgraphing 1941', p.1208+; 'Introducing the Louma Crane', p.1226+ |

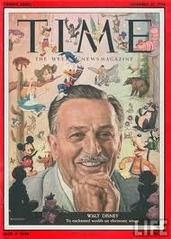

Spielberg paid Walt Disney movies an affectionate tribute in 1941

Much of 1941 is brash,unsubtle and tasteless. But one episode is regularly praised for its charm and the acting skill of Robert Stack. That scene is assumed to be a mark of respect towards Walt Disney. The sequence features Stack as Gen. Joe Stillwell who is shown in a cinema watching Disney's animated movie Dumbo. Outside servicemen riot while he,unknowingly, sits weeping at the plight of the little elephant. Interestingly, Dumbo was released towards the end of 1941; in fact, the uproar over Pearl Harbor meant its initial box office take was diminished. Stillwell was affectionately called 'Uncle Joe' by his troops, and 'Vinegar Joe' by war correspondents. He was probably still stationed in California in early 1942; however, he was thousands of miles away commanding US forces in the far east at the time of the riots shown in the movie. He certainly wasn't watching Dumbo in a Hollywood Boulevard cinema while mayhem ensued outside the cinema. Stillwell had indeed seen the movie, but in Washington D.C. on 25 December 1941. He wrote his wife about having Christmas dinner with an aide and then seeing Dumbo. "I nearly fell off my chair when the elephant pyramid toppled over. We sat through the film twice." [Joseph McBride, Steven Spielberg a Biography , 2nd ed. 2010], pp.302-3

In his own words: Spielberg on 1941

|

" I really thought it would a great opportunity to break a lot of furniture and see a lot of glass shattering. It was basically written and directed as one would perform in a demolition derby....

On about the hundred and forty-fifth day of shooting, I realized that the film was directing me, I wasn't directing it. I'll spend the rest of my life disowning this movie. [Joseph McBride, Steven Spielberg a Biography , 2nd ed. 2010],pp.300-310 |