Tulip Fever (2017)

Originally filmed in 2014, with Justin Chadwick as director, and based on Deborah Moggach's bestselling novel, financial and production problems delayed the release of this movie until 2017. When filming began, Alicia Vikander was just another promising talent, but sinvce then a vaiety of fine performances have made her an up-and-coming star (and probably enabled the film's eventual release).

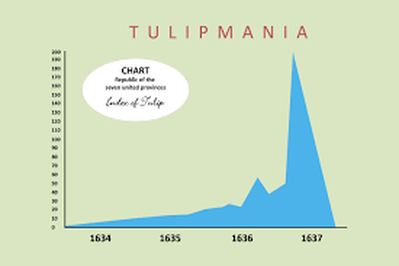

After an interrupted production history, this romantic-historical drama is set in 17th Century Netherlands, during the frenzied brief period (1634-1637) of the boom-and-bust of an unlikely commodity: tulips. During this period of irrational speculation in tulips, fortunes were made and lost against background of financial, familial and romantic intrigue. For a time tulips were used as a form of money. Houses were sold in exchange for a few valuable bulbs.

This dramatic setting is the background for a plot that focuses on a beautiful young Amsterdam orphan (Alicia Vikander) who is forced to marry a wealthy, cold, powerful merchant ( Christoph Waltz). A yoiung artist (Dane Dehaan) is commissioned to paint a portrait of the couple and of course the yoing couple fall in love. In order to make enough money to run away together, the pair try to make a fortune on the volatile tulip market.

The tulip mania appears tp have been one of the first speculative "bubbles". The question is: exactly how widespread was the bubble?

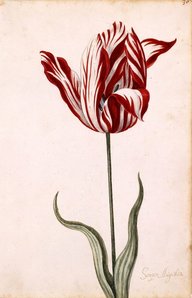

It was not the beautiful tulip flower itself that was valuable during the prief period of the frenzy. The Dutch tulip market traded in the bulbs of exotic and rare species, the most valuable of which was the Semper Augustus variety. An historian of talisman, Mike Dash, describes how a handful of Semper Augustus bulbs sold for 10 000 guilders - "enough to feed, clothe and house a whole Dutch family for half a lifetime, or sufficient to purchase one of the grandest homes on the most fashionable canal in Amsterdam for cash, complete with a coach house and an 80-ft (25-m) garden – and this at a time when homes in that city were as expensive as property anywhere in the world.”

By 1636-7 tens of thousands of people in the United Provinces , ranging from working-class to merchants, bankers and nobility, were caught up in the frenzy. But the overwrought speculative market suddenly collapsed in 1637. Prices had become too high to enable purchases to continue, so demand - and the tulip market - collapsed, bringing financial ruin to thousands.

Or so the story goes. However, recent revisionist interpretations of tulip mania have condemned such views. Petere Garber insist that the so-called tulip frenzy was "was no more than a meaningless winter drinking game, played by a plague-ridden population that made use of the vibrant tulip market."

Anne Goldgar's 2007 book Tulipmania claims that only a small section of the population speculated in tulip, mainly merchants and wealthy skilled craftsmen. She also insists that there was no dire economic collapse resulting from the alleged frenzy. This new interpretation also argues that our conventional view of tulip mania owes a lot to contemporary pamphlets, supposedly written by victims of the 'bubble' but which were in fact morality tales which attacked greed and luxury, and saw the tulip trade as evidence of an attack on public and private morality.

Yet a range of contemporary visual sources strongly suggest that speculation in tulips was significant and widespread. The mania provided a rich source of satire and indignation.

By 1636-7 tens of thousands of people in the United Provinces , ranging from working-class to merchants, bankers and nobility, were caught up in the frenzy. But the overwrought speculative market suddenly collapsed in 1637. Prices had become too high to enable purchases to continue, so demand - and the tulip market - collapsed, bringing financial ruin to thousands.

Or so the story goes. However, recent revisionist interpretations of tulip mania have condemned such views. Petere Garber insist that the so-called tulip frenzy was "was no more than a meaningless winter drinking game, played by a plague-ridden population that made use of the vibrant tulip market."

Anne Goldgar's 2007 book Tulipmania claims that only a small section of the population speculated in tulip, mainly merchants and wealthy skilled craftsmen. She also insists that there was no dire economic collapse resulting from the alleged frenzy. This new interpretation also argues that our conventional view of tulip mania owes a lot to contemporary pamphlets, supposedly written by victims of the 'bubble' but which were in fact morality tales which attacked greed and luxury, and saw the tulip trade as evidence of an attack on public and private morality.

Yet a range of contemporary visual sources strongly suggest that speculation in tulips was significant and widespread. The mania provided a rich source of satire and indignation.