New Zealanders' Campaign Against Hollywood and Movies Part 1

Why Did Movies Arouse the Fears of Moral and Cultural Guardians in New Zealand and Elsewhere?

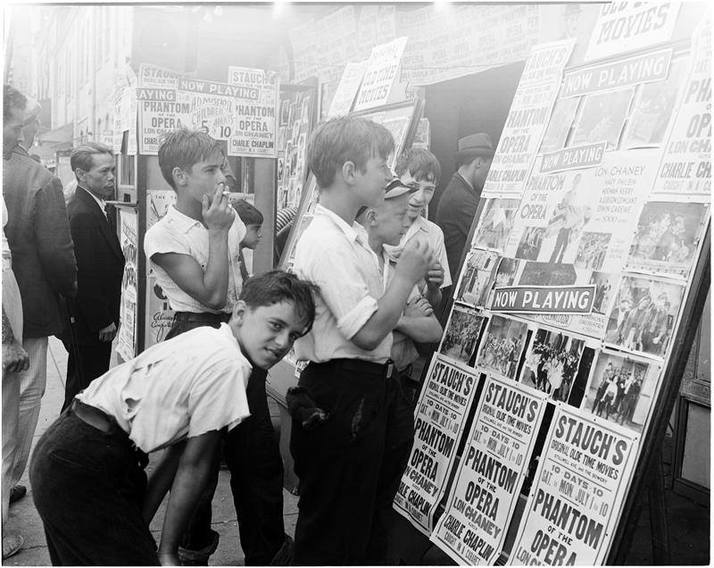

In New Zealand, as in other Western countries, movies were enthusiastically received by the general public from the early 1900s. Yet cultural and moral guardians everywhere immediately regarded them with suspicion and scorn. They demonised film and cinema as sources of virulent moral and cultural contamination from which New Zealanders, especially the young, must be insulated and protected. Movies were depicted as having disastrous consequences for social, civic, educational and ethical behaviours, especially for the young and the less educated, considered to be most susceptible to this new form of entertainment.

In New Zealand, as in other Western countries, movies were enthusiastically received by the general public from the early 1900s. Yet cultural and moral guardians everywhere immediately regarded them with suspicion and scorn. They demonised film and cinema as sources of virulent moral and cultural contamination from which New Zealanders, especially the young, must be insulated and protected. Movies were depicted as having disastrous consequences for social, civic, educational and ethical behaviours, especially for the young and the less educated, considered to be most susceptible to this new form of entertainment.

|

Cultural custodians in New Zealand emulated their American, Canadian, Australian, and European counterparts in immediately setting about prescribing this new medium. In 1916 the New Zealand Parliament passed the Cinematograph-Film Censorship Act, which established film censors empowered to issue certificates of approval to permit films to be shown in theatres.

The 1916 Act resulted from a cleverly organised campaign organised by the New Zealand Catholic Federation, which had gathered under its aegis a cluster of other religious groups, educational authorities, women’s organisations and town councils. The claims of these groups foreshadowed later attempts to restrict the spread of American culture in New Zealand. They alleged that it was the duty of ‘healthy-minded people’ to protect the public, especially children, from ‘the horrible influence of these picture-shows’, which constituted ‘a stream of pollution’. In vain did one M.P., John Payne, demand specific evidence of on-screen immorality. As he noted, the Catholic Federation was primarily agitated about what it claimed were anti-Catholic sentiments in some films. Claims about the protection of public morality were protective coloration that disguised the chief motive of the Federation, and ensured the support of other moral and civic guardian and child-saver groups. This urge of New Zealand's self-appointed cultural guardians to protect children from the allegedly insidious effects of the cinema -notably American cinema - remained constant during the next hald century. |

CASE STUDY: TRUBY KING & PICTURE SHOWS: THEIR EVIL EFFECTS ON CHILDREN ....

The crucial role in this portrayal of movies as poisoning the minds of the young and susceptible was played by the Roual New Zealand Society for the Health of Women and Children. This organisation, started in 1907 Dr Truby King, the pioneering New Zealand expert in child and maternal care. In 1920 the annual conference of that organisation,which was now supported by the government and with its own nurses and clinics throughout New Zealand, produced a pamphlet written by King and significantly entitled Picture Shows. Their Evil Effects on Children, and the Need for Reform, Regulation, and Control. The conference approved a remit denouncing movies as ‘injurious to children and young persons’. It resolved that '‘the class of moving pictures at present exhibited in New Zealand constitutes a grave danger to the moral health of social welfare of the community.' It also demanded ‘That censorship of the pictures should be stricter’ and ‘That pictures for children should be controlled by the Government, through the Education Department....’ 46

King alleged that ‘some of the picture shows are the most degrading things of our age, and have the most damaging influence imaginable. They require to be absolutely censored with regard to children.’ He listed appropriate subjects for the ‘cinematograph’ for ‘all ages’. KIng insisted on documentaries: ‘...illustrating travel, scenery, science, industry, animal and vegetable life....’

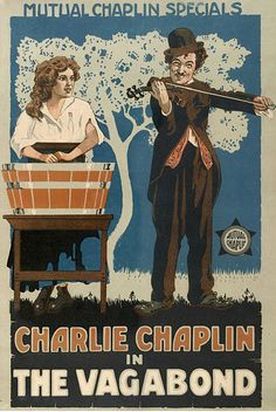

King located cinemas as places of almost magically irresistible temptation to the young - ‘brightly lit, gilded picture palaces which absolutely fascinate the rising generation of today.... every child nowadays comes under the spell of the motion picture’.49 This juvenile audience were shown ‘all that is most despicable and damnable in human nature’, enacted by ‘the coarsest and most debased of human beings’ – actors portraying ‘by unmistakable, exaggerated expressions and gestures the very feelings, passions and depravities from which children should be shielded.’ The content of ‘Picture shows’, King contended, adversely affected the rising generation of children and adolescents.... the whole atmosphere and presentation of life tends to be on a low plane, and fills the young mind with wrong impressions and conceptions as to life’s true values, and as to what should be the aims and ideals of thought, feeling and conduct.

King told of attending cinemas where he saw 'well-dressed boys of good class' watching 'sensual, half-drunken looking blackguards', 'gilded scoundrels', 'flashy, attractive villains'. He was especially perturbed by a movie where 'The piano was played by a negro who had an extraordinary long tumbler beside him which was repeatedly filled with stout.' .

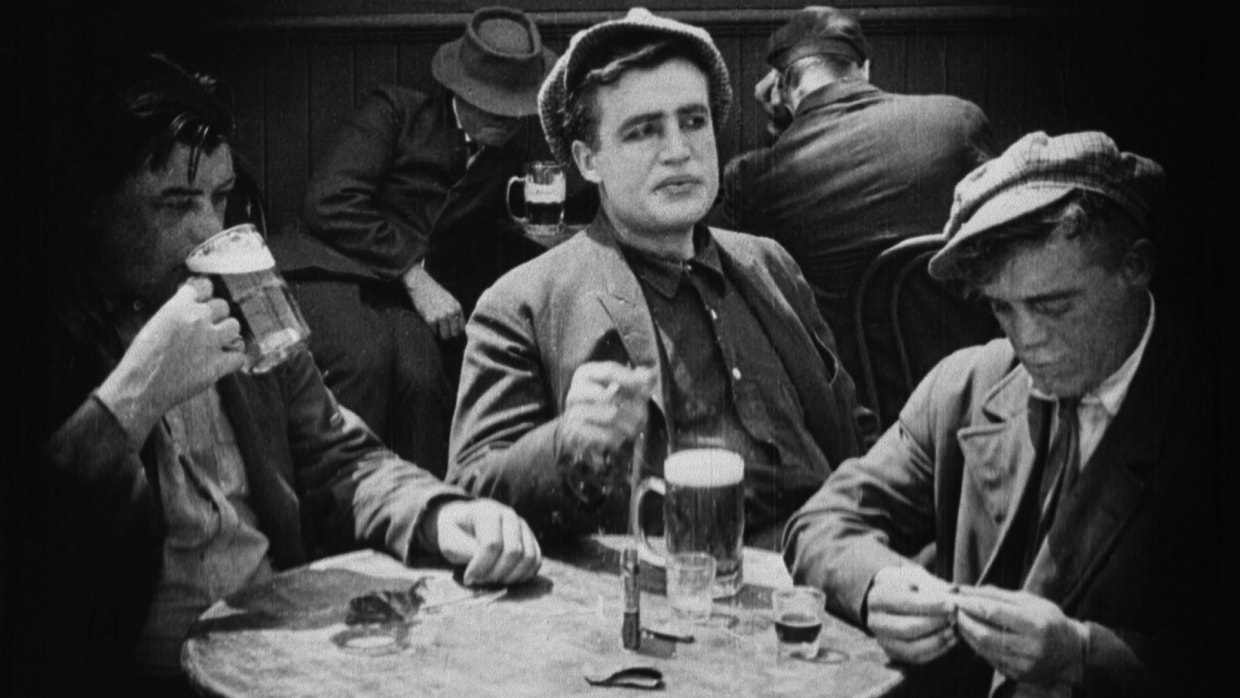

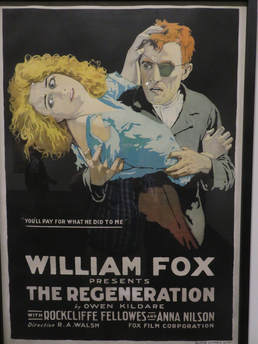

Yet while presenting cinema as sources of dangerous enchantment and malign enthrallment, King also specifically condemned one movie for its realism and verisimilitude. That film was almost certainly The Regeneration, released in 1915-16. Directed by Raoul Walsh, and now regarded as an innovative classic, the movie's publicity emphasised its realism and the fact that it was shot on location in the New York city's rough Bowery area, and used locals (including criminals) as extras for authenticity. Scenes showed domestic abuse, child abuse, drunkenness, prostitution, juvenile crime, violence and attempted rape. King complained : There was no faking: the cinematograph people had spared no pains to present to the life one of the lowest down hells in the Bowery. Instead of employing mere stock actors they had assembled actual blackguards, actual noted criminals, and actual prostitutes, in order to show, with perfect realism, the vice of New York at its worst!

The crucial role in this portrayal of movies as poisoning the minds of the young and susceptible was played by the Roual New Zealand Society for the Health of Women and Children. This organisation, started in 1907 Dr Truby King, the pioneering New Zealand expert in child and maternal care. In 1920 the annual conference of that organisation,which was now supported by the government and with its own nurses and clinics throughout New Zealand, produced a pamphlet written by King and significantly entitled Picture Shows. Their Evil Effects on Children, and the Need for Reform, Regulation, and Control. The conference approved a remit denouncing movies as ‘injurious to children and young persons’. It resolved that '‘the class of moving pictures at present exhibited in New Zealand constitutes a grave danger to the moral health of social welfare of the community.' It also demanded ‘That censorship of the pictures should be stricter’ and ‘That pictures for children should be controlled by the Government, through the Education Department....’ 46

King alleged that ‘some of the picture shows are the most degrading things of our age, and have the most damaging influence imaginable. They require to be absolutely censored with regard to children.’ He listed appropriate subjects for the ‘cinematograph’ for ‘all ages’. KIng insisted on documentaries: ‘...illustrating travel, scenery, science, industry, animal and vegetable life....’

King located cinemas as places of almost magically irresistible temptation to the young - ‘brightly lit, gilded picture palaces which absolutely fascinate the rising generation of today.... every child nowadays comes under the spell of the motion picture’.49 This juvenile audience were shown ‘all that is most despicable and damnable in human nature’, enacted by ‘the coarsest and most debased of human beings’ – actors portraying ‘by unmistakable, exaggerated expressions and gestures the very feelings, passions and depravities from which children should be shielded.’ The content of ‘Picture shows’, King contended, adversely affected the rising generation of children and adolescents.... the whole atmosphere and presentation of life tends to be on a low plane, and fills the young mind with wrong impressions and conceptions as to life’s true values, and as to what should be the aims and ideals of thought, feeling and conduct.

King told of attending cinemas where he saw 'well-dressed boys of good class' watching 'sensual, half-drunken looking blackguards', 'gilded scoundrels', 'flashy, attractive villains'. He was especially perturbed by a movie where 'The piano was played by a negro who had an extraordinary long tumbler beside him which was repeatedly filled with stout.' .

Yet while presenting cinema as sources of dangerous enchantment and malign enthrallment, King also specifically condemned one movie for its realism and verisimilitude. That film was almost certainly The Regeneration, released in 1915-16. Directed by Raoul Walsh, and now regarded as an innovative classic, the movie's publicity emphasised its realism and the fact that it was shot on location in the New York city's rough Bowery area, and used locals (including criminals) as extras for authenticity. Scenes showed domestic abuse, child abuse, drunkenness, prostitution, juvenile crime, violence and attempted rape. King complained : There was no faking: the cinematograph people had spared no pains to present to the life one of the lowest down hells in the Bowery. Instead of employing mere stock actors they had assembled actual blackguards, actual noted criminals, and actual prostitutes, in order to show, with perfect realism, the vice of New York at its worst!

These scenes from Raoul Walsh's 1915 movie Regeneration show the grim realism of life in tbe slums of New York city's Bowery area that so appalled King.

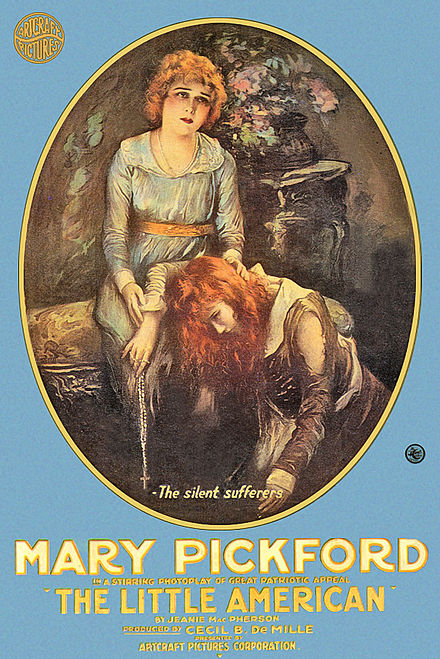

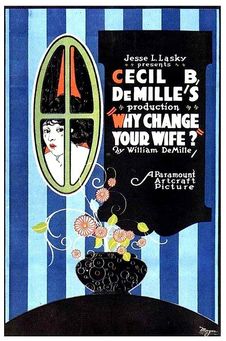

Truby King's animus againt the cinema was echoed in the next decade by fellow guardians of public morality, members of New Zealand's civic and educational elites, who condemned films as decadent and salacious. Thus In the early 1920s the Christchurch M.P. Leonard Isitt claimed cinemas were ‘a source of mental dissipation’ which endangered home life and ‘thousands of our young people’. One historian noted that 'Educational professionals [in the post-1918 period] reinforced the picture of unsophisticated New Zealand youth seduced by the power of the moving pictures.... There is little doubt that most of this moral outrage was directed at American film.'

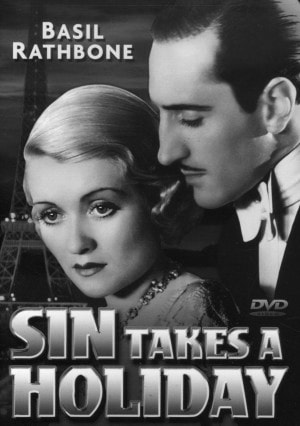

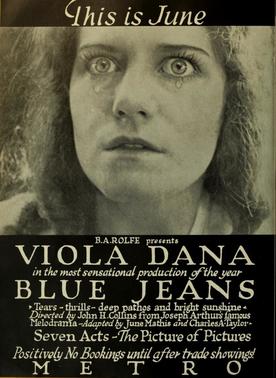

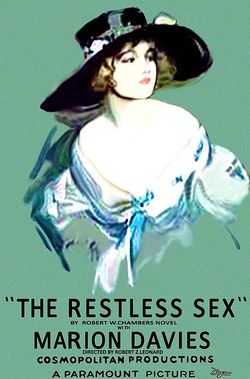

During the twenties and thirties, Hollywood movies came under sustained attack not only for their perceived moral flaws, but also because they were not British in origin, style or subject-matter.

(NZ) Evening Post, 8 January 1913, p.2; 2 December 1915, p.3

NZPD, Vol. 177 (1916), p.573

King, Picture Shows...., p.1; p.4;p.2;p.12;p.11

Roger Openshaw, ‘“The Glare of Broadway”: Some New Zealand Reactions to the Perceived Americanisation of Youth’, Australasian Journal of American Studies, Vol.10 No.1 (July 1991), pp.50-1

Lloyd Chapman, In a Strange Garden the Life and Times of Truby King (Penguin: 2003) Appendix Six.