Waterloo

(Dir: Sergei Bondarchuk, 1970)

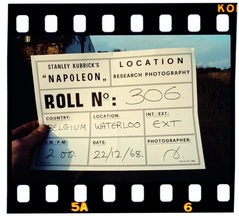

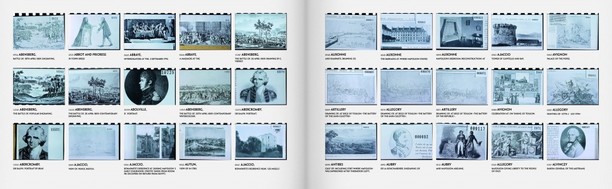

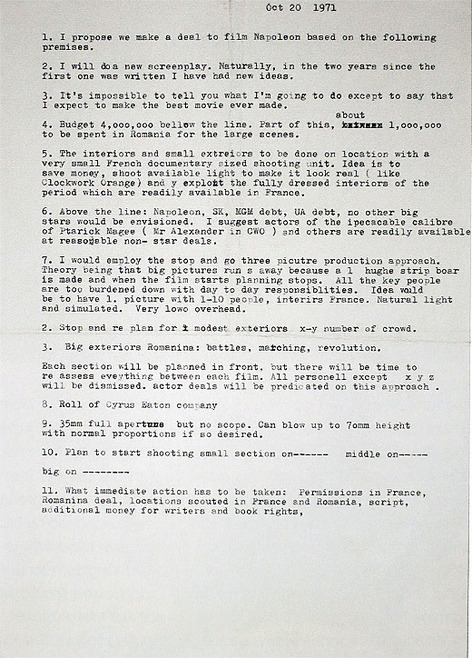

Director Sergie Bondarchuk's epic movie about Napoleon's final battle will be forever doomed to be looked at askance because of its unfortunate and unintended impact on Stanley Kubrick, one of the twentieth century's cinematic geniuses. Kubrick had long intended to make a grand movie about Napoleon and had spent at least four years working on a screenplay and drawing thousands of pages on notes and information ranging from casting, costumes, and battles, to personalities, locations, art, and music. But Waterloo - a well-intentioned film with excellent set pieces, its many battle scenes directed with Bondarchuk's customary flair - was poorly received by the critics of the time. The New York Times, for example, condemned it as "a very bad film" directed wih the "subdued refinement of a sledgehammer." Roger Ebert complained that the director was "so overwhelmed by the thousands of Russian cavalry troops he's been given to play with, and by his $25 million budget, and by-his obsession for aerial photography, that his leading characters turn out scarcely more human than his extras. "

Even worse, Waterloo was a financial flop. Kubrick found that his dream project was now unable to obtain the studio and financial backing it needed. He unsuccessfully tried for several years to get that backing. So what has been called "the greatest movie never made" was eventually dropped from Kubrick's list of projects.

Even worse, Waterloo was a financial flop. Kubrick found that his dream project was now unable to obtain the studio and financial backing it needed. He unsuccessfully tried for several years to get that backing. So what has been called "the greatest movie never made" was eventually dropped from Kubrick's list of projects.

|

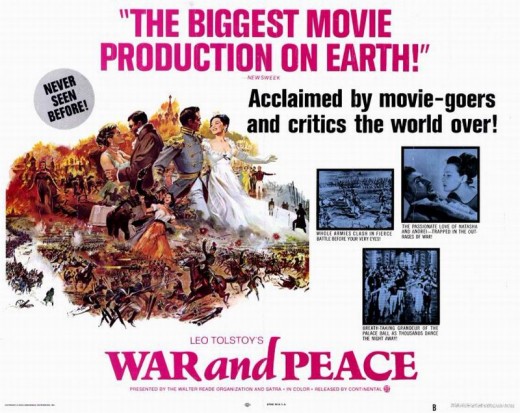

The commercial and (in America) the critical failure of Waterloo was a first for director Sergei Bondarchuk. For years he had been Russia's most acclaimed director. The success of his massive seven-hour long cinematic version of War and Peace had brought him international acclaim and won the 1969 Academy Award for best Foreign Language film. He was also applauded for his performance as Pierre Bezukhov.

War and Peace remains the most expensive movie ever made: about $US 830 million. It took seven years to make, used the services of tens of thousands of Red Army soldiers, more than two thousand cavalrymen, employed hundreds of professional actors.The sequence showing the battle of Borodino remains the longest battle scene ever made. Bondarchuk knew something about both war and acting. Born in the Ukraine in 1920, his youthful interest in the stage led him to study drama at Rostov until the German invasion of Russia in 1941. He spent the next four years fighting for the Red Army. After the war he resumed his acting studies and soon became one of the USSR's best young screen actors. In 1959 he directed his first film, Fate of a Man, a World War 2 drama that was widely praised in Russia and Europe. This success enabled Bondarchuk to attempt the colossal task of translating Tolstoy's epic novel to the screen. Unfortunately the international success of War and Peace had unfortunate politcal repercussions for Bondarchuk. Brezhnev's Soviet government "invited" him to join the Communist Party. To refse would have meant the end of his days as a director and actor. (It also meant he could use the manpower and resources of the Russian army to make Waterloo).He was soon "elected" Chairman of the Union of Soviet Filmmakers and consequently his talents were wasted on making some movies that refelected Soviet propaganda rather than his artistic talents. It wasn't until two decades later that he was able to exercise some freedom of choice by making a movie of the Russian novel And Quiet Flows the Don. But a bitter legal dispute between director and producers meant that the movie was never completed before Bondarchuk's death. Below: scenes from Bondarchuk's War and Peace |

Waterloo: the Movie and Its Problems

With the benefit of hindsight, it's easy to see why Bondarchuk's epic was doomed to critical and commercial failure (as well as bearing the blame for Kubrick's inability to finance his planned Napoleon masterpiece). Movie critics always love to mock excess, and Waterloo's publicity about the movie's huge costs and massive number of extras seemed to invite skepticism. Then there's the question of casting. Neither Rod Steiger (Napoleon) nor Christopher Plummer (Wellington) were exactly box office magnets. Steiger portrays Napoleon as surly, rather ponderous, constantly complaining. He's hardly the charismatic figure of Napoleon legend, although in fact at this stage of his career Bonaparte was indeed a grumpy, stout, short-tempered man whose military (and physical) powers were declining. But to focus a long movie around such a figure is risky. Plummer's portrayal of Wellington is livelier and much more entertaining, capturing the man's sardonic, cool, calculating personality leavened with occasional cutting humour. But the rivalry between the two soldiers is hardly dynamic on the screen.

The movie's subject-matter is another big problem. It's essentially a couple of hours of an early nineteenth century European battle - a crucial, historically very significant battle, but it's still a conflict involving people, strategies, policies, military tactics, locations, uniforms and weapons that by 1970 were virtually unknown by most moviegoers. The movie assumes that its audiences will know about, and be interested in, the Napoleonic wars, Wellington and Bonaparte, and the significance of the battle itself. Furthermore, there are no interesting back-stories, or romantic sub-plots as in War and Peace. And the movie was picked to death by finicky perfectionists who objected to such details as the fashionable colour of bridal gowns in 1815, the civilian clothes Picton wore to battle, the slope of a strategic valley, authenticity of weapons, breeds of horses, formation of infantry squares etc etc. And the movie's script is rather wooden and conventional.

With the benefit of hindsight, it's easy to see why Bondarchuk's epic was doomed to critical and commercial failure (as well as bearing the blame for Kubrick's inability to finance his planned Napoleon masterpiece). Movie critics always love to mock excess, and Waterloo's publicity about the movie's huge costs and massive number of extras seemed to invite skepticism. Then there's the question of casting. Neither Rod Steiger (Napoleon) nor Christopher Plummer (Wellington) were exactly box office magnets. Steiger portrays Napoleon as surly, rather ponderous, constantly complaining. He's hardly the charismatic figure of Napoleon legend, although in fact at this stage of his career Bonaparte was indeed a grumpy, stout, short-tempered man whose military (and physical) powers were declining. But to focus a long movie around such a figure is risky. Plummer's portrayal of Wellington is livelier and much more entertaining, capturing the man's sardonic, cool, calculating personality leavened with occasional cutting humour. But the rivalry between the two soldiers is hardly dynamic on the screen.

The movie's subject-matter is another big problem. It's essentially a couple of hours of an early nineteenth century European battle - a crucial, historically very significant battle, but it's still a conflict involving people, strategies, policies, military tactics, locations, uniforms and weapons that by 1970 were virtually unknown by most moviegoers. The movie assumes that its audiences will know about, and be interested in, the Napoleonic wars, Wellington and Bonaparte, and the significance of the battle itself. Furthermore, there are no interesting back-stories, or romantic sub-plots as in War and Peace. And the movie was picked to death by finicky perfectionists who objected to such details as the fashionable colour of bridal gowns in 1815, the civilian clothes Picton wore to battle, the slope of a strategic valley, authenticity of weapons, breeds of horses, formation of infantry squares etc etc. And the movie's script is rather wooden and conventional.

Yet the movie has several points in its favour. It manages to include the essential elements of a complicated battle in which crucial encounters were occurring sometimes simultaneously and a considerable distance apart. In accordance with recent scholarship Waterloo makes it clear that the Prussian von Blucher's intervention at the end of the day of slaughter was the decisive blow on the Emperor's right wing that doomed Napoleon's armies. And even if Steiger's portrayal of Napoleon is rather dour and plodding, that is how Napoleon appeared at Waterloo: devoid of his customary military genius and inspiration. The movie also provides some insight into the battlefield carnage. As many as 31 000 Frenchmen were killed or wounded; Wellington and his Prussian ally Blucher lost a total of about 24 000 men. Even the confused and brutal hand-to-hand struggles around the two amazingly strong farmhouses at Hougoument and La Haie Sainte are given the significance they deserve.

But above all Bondarchuk's movie succeeds primarily as sheer enjoyable and exciting battlefield spectacle, especially as viewed in its original cinematic widescreen release. The panoramic and aerial shots of thousands of men, horses and artillery manoeuvring almost balletically is very impressive, as is Bondarchuk's depiction of close-quarter combat. The images below indicate how impressive Waterloo was as a big-screen spectacle .

But above all Bondarchuk's movie succeeds primarily as sheer enjoyable and exciting battlefield spectacle, especially as viewed in its original cinematic widescreen release. The panoramic and aerial shots of thousands of men, horses and artillery manoeuvring almost balletically is very impressive, as is Bondarchuk's depiction of close-quarter combat. The images below indicate how impressive Waterloo was as a big-screen spectacle .

|

|

|