Rebel Without a Cause Dir: Nicholas Ray (1955)

Rebel Without a Cause: the background

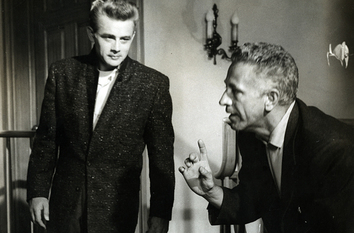

Director Nicholas Ray instructing a youthful Dennis Hopper.

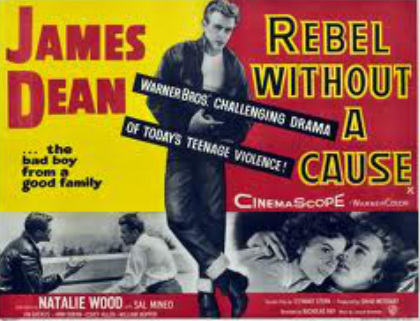

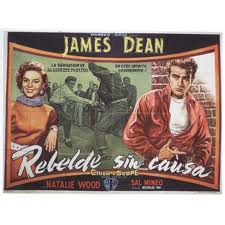

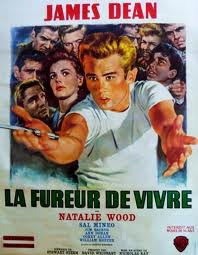

As these three posters for foreign-language versions of Rebel Without a Cause suggest, the movie was publicised worldwide as a movie about troubled youth. In fact 'Rebel' was also aimed at an older generation of filmgoers and far from being a gritty expose of American teenage culture was actually an upmarket studio 'prestige' production which shrewdly aimed to take advantage of the publicity surrounding the new acting sensation, James Dean. Dean's previous movie, East of Eden, had won the actor critical and popular acclaim. The fact that Dean was killed just before the movie was released only increased the public interest in his portrayal of a troubled teenager. Originally, Rebel Without a Cause was intended to be just another Warner Bros B-movie, shot in black and white in standard format. But the wave of publicity surrounding Dean and the emergence of youth culture as a a political and public issue meant that Warner Bros shrewdly decided to move the film upmarket even as it was being shot. Filming began again in colour, using the more expensive Cinemascope widescreen format.

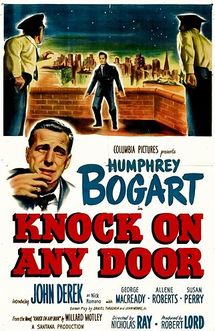

Many of the claims about Rebel as innovatory are nonsense. It was not the first movie about troubled teens, nor was it the first to examine teenager-parent clashes. These had been movie staples since at least the 1930s. Seven years earlier Knock On Any Door and City Across the River had examined the phenomenon of teenage crime and violence within the context of the big-city working class environment. Knock On Any Door was directed by Nicholas Ray, and it argued that the roots of juvenile crime lay in the deprived slum environments in which many youths lived. Even Rock Around the Clock and Don't Knock the Rock relied heavily on the youth versus older generation theme. Nor was it new in depicting teenage violence and bravado in the form of fights and car races - these were features of the cheap 'teenager' movies of the early and mid-1950s, more sensationalised but often more vigorously and concisely presented than in Rebel.

Many of the claims about Rebel as innovatory are nonsense. It was not the first movie about troubled teens, nor was it the first to examine teenager-parent clashes. These had been movie staples since at least the 1930s. Seven years earlier Knock On Any Door and City Across the River had examined the phenomenon of teenage crime and violence within the context of the big-city working class environment. Knock On Any Door was directed by Nicholas Ray, and it argued that the roots of juvenile crime lay in the deprived slum environments in which many youths lived. Even Rock Around the Clock and Don't Knock the Rock relied heavily on the youth versus older generation theme. Nor was it new in depicting teenage violence and bravado in the form of fights and car races - these were features of the cheap 'teenager' movies of the early and mid-1950s, more sensationalised but often more vigorously and concisely presented than in Rebel.

Nicholas Ray's 1949 movie looked at juvenile delinquency as a product of socio-economic deprivation, not as middle-class angst

Even the film's title was dated: it was taken from a 1944 article by Robert Lindner, entitled "Rebel Without a Cause: the Hypoanalaysis of a Criminal Psychopath", a Freudian analysis of a troubled teenager. In 1954 Lindner, had told Time magazine that modern American youth was committing "a devil's rosary of crimes ranging from rape to murder, and all stamped with an unbelievable degree of sadism". This was caused by teenagers' troubled psychological condition which left them alienated from society; the only cure was psychological therapy.

Rebel Without a Cause follows Linder's argument: the teenager was an innocent victim of familial and psychological forces, but one capable of redemption. But although one feels sympathy for the problems of the Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo characters, Dean's character tends to self-pity, and a not particularly justified sense of victimhood.He has a privileged middle class suburban lifestyle. Ray emphasises he is torn by the conflict between the parents but that conflict onscreen is stereotyped and unconvincing. The teenage hero in Knock on an Door, and the school students in Blackboard Jungle, by contrast, have bigger problems - social and economic deprivation, a school system that ignores their needs, ingrained racism -problems that will not be solved by psychological analysis or a return to traditional parenting roles.

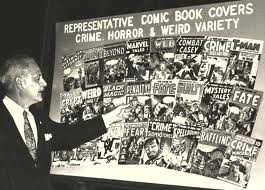

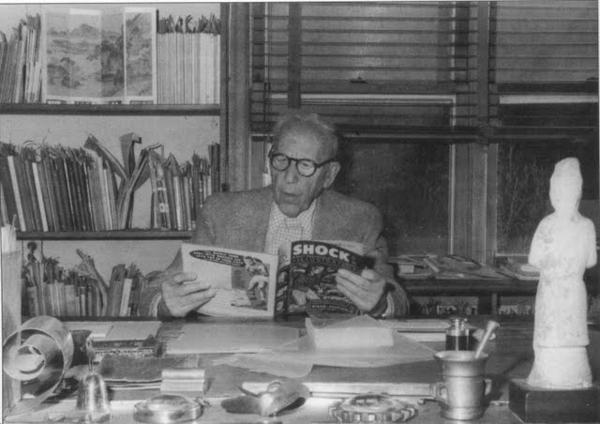

The movie was astutely marketed to take advantage of several currently controversial issues. The 1953 movie The Wild One, which featured Marlon Brando giving one of his most mannered performances and which relied heavily on the theme of a disgruntled younger generation (but not teenagers) set against a background of motorbike gangs and conflict with the law had been the focus of a media and political furore. Another alleged form of youthful rebellion, namely rock 'n' roll music, had also become newsworthy during the 1955-56 period. And just a few months earlier, Blackboard Jungle - a much better film than Rebel - had become a great critical and box-office success, with its convincing portrayal of youthful delinquency in New York city's public school system and that system's failure to deal with the needs of working class youth. Furthermore, the topics of juvenile delinquency and teenage culture had become politically and intellectually fashionable. Mass culture in the form of 'comics', music and movies was supposedly corrupting American youth. Senator Estes Kefauver, campaigning for the 1956 Democratic Party presidential nomination, used his leadership of a Congressional sub-committee on comics and pulp fiction, to publicise his candidature and provide him with a winnable election issue.

Rebel Without a Cause follows Linder's argument: the teenager was an innocent victim of familial and psychological forces, but one capable of redemption. But although one feels sympathy for the problems of the Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo characters, Dean's character tends to self-pity, and a not particularly justified sense of victimhood.He has a privileged middle class suburban lifestyle. Ray emphasises he is torn by the conflict between the parents but that conflict onscreen is stereotyped and unconvincing. The teenage hero in Knock on an Door, and the school students in Blackboard Jungle, by contrast, have bigger problems - social and economic deprivation, a school system that ignores their needs, ingrained racism -problems that will not be solved by psychological analysis or a return to traditional parenting roles.

The movie was astutely marketed to take advantage of several currently controversial issues. The 1953 movie The Wild One, which featured Marlon Brando giving one of his most mannered performances and which relied heavily on the theme of a disgruntled younger generation (but not teenagers) set against a background of motorbike gangs and conflict with the law had been the focus of a media and political furore. Another alleged form of youthful rebellion, namely rock 'n' roll music, had also become newsworthy during the 1955-56 period. And just a few months earlier, Blackboard Jungle - a much better film than Rebel - had become a great critical and box-office success, with its convincing portrayal of youthful delinquency in New York city's public school system and that system's failure to deal with the needs of working class youth. Furthermore, the topics of juvenile delinquency and teenage culture had become politically and intellectually fashionable. Mass culture in the form of 'comics', music and movies was supposedly corrupting American youth. Senator Estes Kefauver, campaigning for the 1956 Democratic Party presidential nomination, used his leadership of a Congressional sub-committee on comics and pulp fiction, to publicise his candidature and provide him with a winnable election issue.

The uproar over comics, rock 'n' roll and movies like The Wild One and Rebel Without a Cause provides a fascinating example of how educational elites in the USA and elsewhere allied with civic and political groups to act as cultural guardians and moral entrepreneurs. They functioned as self-appointed gatekeepers,seeking to restrict or deny susceptible youth access to cultural forms that they deemed to be vulgar, lower-class and lacking the attributes of so-called 'high' culture. These elites shrewdly claimed that the youthful offspring of the middle classes were endangered by these new cultural phenomena. In the USA communists were frequently accused of spreading such pernicious media in order to break down the family and erode traditional moral values. In France, Britain, Australia and New Zealand on the other hand, groups on the left blamed American capitalist media for trying to subvert youthful morals and behaviour. Their argument was addressed to the middle-class parents of these nations.

Although Rebel Without a Cause is usually cited as a ground-breaking, even subversive movie in its approach to juvenile deliquency and youth, in fact it is very much a middle-class movie. The Stark family are comfortably middle class, well-housed, the son uses a late-model expensive car, his new school peers are obviously comfortably off, their school provides visits to a planetarium. This is a privileged, affluent, indulged group, lazy and bored. Stark himself has a well-developed sense of victimhood that he uses to justify his behaviour. Compared with the working-class backgrounds of the teens in Blackboard Jungle and City Across the River, and even Ray's earlier Knock on Any Door, Stark and his friends have got it easy - no slums, no rundown schools, no racism, no poverty, no violent gangs.

The problems faced by Jim Stark and his friends are essentially familial and psycholological, not societal or economic. The weakest feature of the movie is its portrayal of the Stark parents, reduced to clumsy caricatures: dominant, forceful mother and weak, passive, submissive father - a reversal of supposedly conventional parental roles. As Peter Biskind argues, the movie is essentially conservative: restore the 'traditional' parental roles and the troubled teenager will be cured.

Although Rebel Without a Cause is usually cited as a ground-breaking, even subversive movie in its approach to juvenile deliquency and youth, in fact it is very much a middle-class movie. The Stark family are comfortably middle class, well-housed, the son uses a late-model expensive car, his new school peers are obviously comfortably off, their school provides visits to a planetarium. This is a privileged, affluent, indulged group, lazy and bored. Stark himself has a well-developed sense of victimhood that he uses to justify his behaviour. Compared with the working-class backgrounds of the teens in Blackboard Jungle and City Across the River, and even Ray's earlier Knock on Any Door, Stark and his friends have got it easy - no slums, no rundown schools, no racism, no poverty, no violent gangs.

The problems faced by Jim Stark and his friends are essentially familial and psycholological, not societal or economic. The weakest feature of the movie is its portrayal of the Stark parents, reduced to clumsy caricatures: dominant, forceful mother and weak, passive, submissive father - a reversal of supposedly conventional parental roles. As Peter Biskind argues, the movie is essentially conservative: restore the 'traditional' parental roles and the troubled teenager will be cured.

|

|

|

After Rebel: more movies about juvenile delinquency

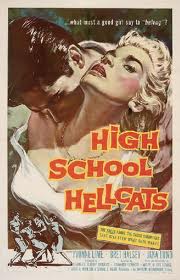

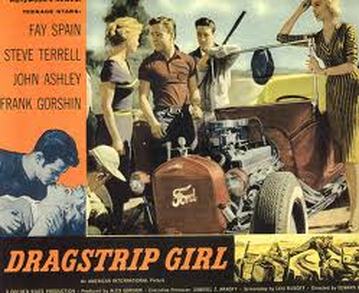

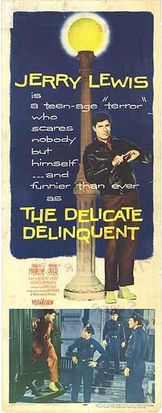

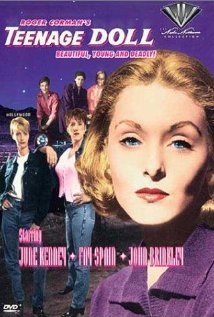

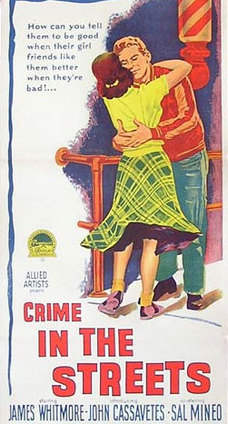

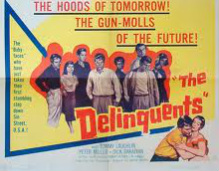

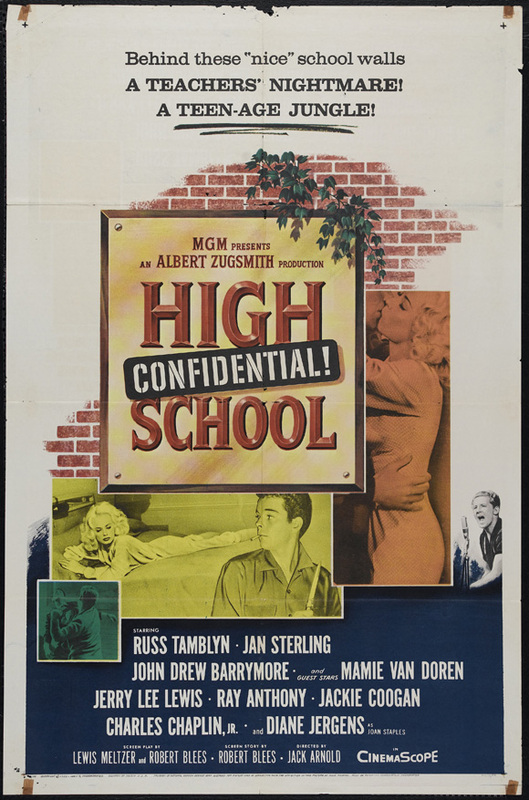

The box-office success of Rebel and the iconic image of the deceased James Dean as embittered,frustrated, moody teenage victim of course resulted in Hollywood quickly adapting many of the movie's motifs and settings. For the next few years there were countless movies - most aimed at a teenage audience - featuring disaffected youths, conflicts with the law, gangs and untalented young actors trying to convey Dean's surly appeal. Many of those cast as teenagers were obviously years older (e.g. High School Confidential). The chicken-run and knife-fight scenes of Ray's movie were repeated with hot-rod races and gang brawls. Roger Corman occasionally included a Rebel-type movie (like Teenage Doll) amongst his lineup of horror and science-fiction movies.Some new, young directors were given opportunities to show their skills: Don Siegel directed Crime in the Streets and Robert Altman self-financed his first film, The Delinquents.

Although most of these post-Rebel and post-Blackboard Jungle movies were exploitive, sensationalist, suffered from clumsy scripts, bad acting, and clumsy directing, they had two significant features. Unlike Rebel, most were set in a non middle-class background, with characters having working-class occupations (or no occupations at all). Indeed, crime was sometimes their occupation and a key motif was whether or not key characters would succumb to the temptation of easy money achieved illegally. The films were often set in squalid, run-down areas. Psychological problems were not an issue, but revenge and sex were. More importantly, some of these movies gave females an important role. They were sometimes crucially involved in activities supposedly the domain males e.g. motor-cars, drag-racing, gang activities. And these girls act forcefully: they scheme, plot, bully and initiate criminal activities. They order males around. Some are portrayed as fearless and capable drivers or troublemakers.

Siegel's 1956 Crime in the Streets is an interesting exception. This noirish movie combines elements of Rebel Without a Cause, Blackboard Jungle and City Across the River. Its setting is an urban ghetto, its story is based on youthful street gang crime, it has an adult mentor figure (a social worker) trying to save the 18 year-old hero from falling into a life of crime and violence.

Although most of these post-Rebel and post-Blackboard Jungle movies were exploitive, sensationalist, suffered from clumsy scripts, bad acting, and clumsy directing, they had two significant features. Unlike Rebel, most were set in a non middle-class background, with characters having working-class occupations (or no occupations at all). Indeed, crime was sometimes their occupation and a key motif was whether or not key characters would succumb to the temptation of easy money achieved illegally. The films were often set in squalid, run-down areas. Psychological problems were not an issue, but revenge and sex were. More importantly, some of these movies gave females an important role. They were sometimes crucially involved in activities supposedly the domain males e.g. motor-cars, drag-racing, gang activities. And these girls act forcefully: they scheme, plot, bully and initiate criminal activities. They order males around. Some are portrayed as fearless and capable drivers or troublemakers.

Siegel's 1956 Crime in the Streets is an interesting exception. This noirish movie combines elements of Rebel Without a Cause, Blackboard Jungle and City Across the River. Its setting is an urban ghetto, its story is based on youthful street gang crime, it has an adult mentor figure (a social worker) trying to save the 18 year-old hero from falling into a life of crime and violence.

|

|

|