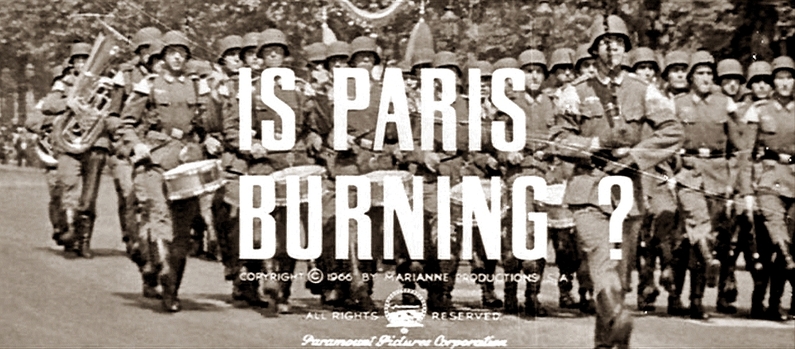

Is Paris Burning? (Paris Brule-t-il ?) Dir: Réne Clément 1996

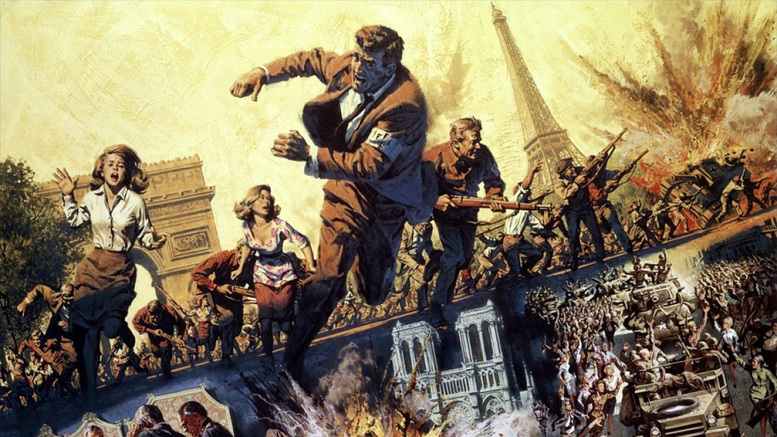

A fatal flaw: Is Paris Burning? tried to treat 1944's liberation of Paris as both a Hollywood spectacle and a semi-documentary.

Is Paris Burning? was a critical and financial flop when released in 1966. Why?

And why has its reputation increased decades later?

What's the movie about?"Is Paris burning?" was the question Hitler asked of Alfred Jodl, his Chief of Staff on 25 August, 1944, hours before Paris was liberated from Nazi rule. Hitler had previously ordered Paris's military governor, General Dietrich von Choltitz, to destroy the city before it was liberated by Allied forces. Twenty years later two journalists, Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre, wrote a fascinating account of how and why Paris was saved from Hitler's order for its destruction. Called Is Paris Burning?, the book was a world-wide best-seller. According to the authors' version, von Choltitz disobeyed Hitler and set about to save Paris from destruction. However, there is some dispute as to exactly how important his role was and whether he deserves to be regarded as the saviour of Paris. Inevitably, Hollywood decided to finance a movie based on the events of late August,1944.

|

Is Paris Burning? seemed initially to have so many points in its favor.

Its subject matter seemed well suited to cinematic treatment. It dealt with truly epic events: the threatened destruction of Paris and then the triumphant liberation of that city. It involved a deadline with enormous consequences (always a favoured movie device). It investigated a fascinating issue - just how had Hitler's plan been thwarted? Several of the historical figures were equally interesting, ranging from Dietrich von Choltitz, the German military commander of Paris to Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French, the impetuous American General George Patton and two key figures in the French Resistance, Philippe Leclerc and Henri Rol-Tanguy. Several of the world's best movie-makers of the 1960s were involved in the project. The choice of Réne Clément as director seemed auspicious. He had belonged to the Resistance and had previously made two excellent films about Nazi occupation: Battle of the Rails and The Quiet Father [Cliomuse.com pages]. By the mid-sixties Clément was one of international cinema's most highly regarded directors, noted for his ability to combine emotional intensity with taut plots wand a distinctive visual style. The script was written by Gore Vidal and the promising youngster Francis Ford Coppola. The film's music was in the hands of Maurice Jarre and the cinematographer was Marcel Grignon, who shot the movie in a distinctive, gritty black-and-white documentary style. Finally, the makers of the film employed an international cast that included Jean-Paul Belmondo, Kirk Douglas, Glenn Ford, Orson Welles, Simone Signoret and Anthony Perkins. Gert Frobe, fresh from his success in Goldfinger, had the vital role of General Von Choltitz; Orson Welles featured as Raoul Nordling, the Swedish consul who tried to persuade the general to disobey Hitler.

Unfortunately, the movie proved to be a critical and commercial flop. It was not until almost a half century later that movie-makers returned to the von Choltitz / Nordling controversy in 2014's Diplomacy (Diplomatie), which focuses almost entirely on the battle of wits between the two men.

So what went wrong?

1. The movie failed to focus on why and how Hitler's order to destroy Paris was not implemented by von Choltitz.

Its subject matter seemed well suited to cinematic treatment. It dealt with truly epic events: the threatened destruction of Paris and then the triumphant liberation of that city. It involved a deadline with enormous consequences (always a favoured movie device). It investigated a fascinating issue - just how had Hitler's plan been thwarted? Several of the historical figures were equally interesting, ranging from Dietrich von Choltitz, the German military commander of Paris to Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French, the impetuous American General George Patton and two key figures in the French Resistance, Philippe Leclerc and Henri Rol-Tanguy. Several of the world's best movie-makers of the 1960s were involved in the project. The choice of Réne Clément as director seemed auspicious. He had belonged to the Resistance and had previously made two excellent films about Nazi occupation: Battle of the Rails and The Quiet Father [Cliomuse.com pages]. By the mid-sixties Clément was one of international cinema's most highly regarded directors, noted for his ability to combine emotional intensity with taut plots wand a distinctive visual style. The script was written by Gore Vidal and the promising youngster Francis Ford Coppola. The film's music was in the hands of Maurice Jarre and the cinematographer was Marcel Grignon, who shot the movie in a distinctive, gritty black-and-white documentary style. Finally, the makers of the film employed an international cast that included Jean-Paul Belmondo, Kirk Douglas, Glenn Ford, Orson Welles, Simone Signoret and Anthony Perkins. Gert Frobe, fresh from his success in Goldfinger, had the vital role of General Von Choltitz; Orson Welles featured as Raoul Nordling, the Swedish consul who tried to persuade the general to disobey Hitler.

Unfortunately, the movie proved to be a critical and commercial flop. It was not until almost a half century later that movie-makers returned to the von Choltitz / Nordling controversy in 2014's Diplomacy (Diplomatie), which focuses almost entirely on the battle of wits between the two men.

So what went wrong?

1. The movie failed to focus on why and how Hitler's order to destroy Paris was not implemented by von Choltitz.

Although some historians dispute Collins and LaPierre's focus on von Choltitz as the crucial factor in preventing Hitler's plan to destroy Paris, at least their account had the merit of anchoring what could easily have become a confusing and wayward narrative. But this is exactly what the movie version failed to do. Instead, the movie's narrative is splintered into several strands: von Choltitz's efforts, the intermediary work of the Swedish Consul Raoul Nordling, the role of the Resistance; the tactics of the approaching Allied forces. As the movie proceeds, the significance of von Choltitz and his motives and tactics becomes increasingly neglected. Gert Frobe's performance as the general is rather one-dimensional; he fails to make this enigmatic, shrewd figure sufficiently interesting.

2. The movie crams in too many people and incidents which distract rather than enhance the viewer's focus.

2. The movie crams in too many people and incidents which distract rather than enhance the viewer's focus.

The film's American production company, Paramount, decided that Is Paris Burning? should feature cameo performances from a range of international stars, including Charles Boyer, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Glenn Ford. Unfortunately, this was at odds with director Clement's decision to use a semi-documentary style which integrated newsreel footage with movie shots designed to have the gritty,improvised look of documentary. In those pre-digitised days this was a difficult task, but the end result looked remarkably authentic - with one major drawback. Apparently authentic sequences were marred by the appearance of the likes of Kirk Douglas, Robert Stack, or sixties hearthrob George Chakiris. The use of so many guest stars bloated the film and slowed its momentum. Not only did this decision fragment the narrative; it also made the movie appear commercialised and contrived. There was another problem, too. Many of these stars of past and present delivered mediocre, bland performances, especially Orson Welles and Leslie Caron.

3. Viewer confusion about who was doing what, where, when and why.

3. Viewer confusion about who was doing what, where, when and why.

Not only did Is Paris Burning? involve a bewildering number of people whose identities were, by the mid-sixties, unknown to many viewers. The movie also failed to explain adequately the significance of who they were and what they did in the context of the Liberation. The film lacked the book's advantage of being able to look up a list that identified the key participants and outlined their roles. And the book also provided the reader with maps that pinpointed key locations in the city, making it easier to understand what was happening. But the movie version set itself an impossible task. Its sweeping perspective, involving von Choltitz, the Resistance, the Swedish ambassador, the Allied armies, plus sundry civilian participants meant that viewers were inevitably confused as to what exactly was going on. Indeed, at the time those involved were confused too, such was the pace and scope of events. Few imovie-goers knew about Resistance groups, Allied military tactics and French wartime politics.

Even today, historians argue about the causes and consequences of some events, and dispute the roles played by key groups and particiipants. So its not surprising that audiences complained they were confused about what they saw onscreen.

4. The movie was made at the worst possible time, given the political and social context of the 1960s.

Even today, historians argue about the causes and consequences of some events, and dispute the roles played by key groups and particiipants. So its not surprising that audiences complained they were confused about what they saw onscreen.

4. The movie was made at the worst possible time, given the political and social context of the 1960s.

Is Paris Burning? had the bad luck to be released at a time of increasingly bitter political, social and cultural argument, not only in France but also in western Europe and the USA.

Réne Clément's movie took the traditional view of the Liberation of Paris, and the attitude of French people towards the Nazi Occupation. That is, the Liberation is portrayed as a triumph of popular French determination to overthrow Nazi rule, a determination exemplified by the courageous struggle of Resistance forces, which readily ignored their differing political outlooks in order to unite to overthrow the hated German occupiers and liberate Paris.

This view was increasingly being attacked even as the film was being made. Communists claimed that their members were the dominant force in the Resistance and in opposing the Germans in Paris; supporters of President Charles de Gaulle claimed that the Gaullist Free French forces and Gaullist-oriented Resistance units were crucial. Veterans of the Division Leclerc and other Allied forces demanded that their role in liberating Paris be emphasised. DeGaulle's own role was contentious. His supporters regarded him as the saviour of Paris and France; his opponents insisted he was an arrogant and divisive figure who took credit for the contributions that other French men and women had made in their struggle against the Nazis. Another even more discordant element emerged in the publicity over the book and its transference into a movie. It was becoming clear that the majority of Parisians were acquiesced passively in the German occupation, and a considerable number actively assisted Occupation forces and / or profited economically or politically from that Occupation. Very few French actually joined or helped the Resistance. It was only when it became clear that the Allied invading forces had established an irreversible presence in France that the populations of Paris and other French cities decided to rise up against their German occupiers.

Not only did the movie face this mixture of embarrassment and backlash against the traditional heroic view of the Liberation. It became mired in the controversies about President de Gaulle. His political opponents of left and right in France denounced the film for presenting him as a a popular and unifying force. In America many hated him for his 1966 demand that US forces leave Vietnam and his decision that same year to pull France out of NATO. Many in Britain also resented that stance, as well as his negative attitude towards British entry into the EEC. Many Anglo-Americans accused him of ingratitude: he had been willing to accept Allied help during World War 2 but had now turned his back on his former benefactors. And with peace movements and anti-war demonstrations flourishing, an American-financed film about military exploits was unlikely to do well.

One unfortunate result of the various backlashed against the movie was the disastrous effects on the reputation of its director, Réne Clément. His reputation never recovered from the critical and financial mauling the film received. The New Wave-style aficianados already regarded his carefully-honed, well-crafted and subtle films as old-fashioned, so the failure of Paris provided them with a perfect opportunity to condemn his oeuvre.

What's good about Is Paris Burning?

1. The decision to film in black-and-white documentary style, making frequent use of hand-held cameras, and using the actual locations (or close approximations) makes for an authentic experience. At times it seems as if you are there on the streets of Paris watching events. The integration of actual documentary footage with film is very well done, especially considering that the film was made years before the days of CGI and computerisation. Features of this style were used years later to good effect by Spielberg in Schindler's List.

2. Many of the sequences in the movie are exciting and convincing. Clément is brilliant at action set-pieces, especially scenes of Resistance fighters ambushing German troops. His use of the widescreen format cleverly uses the wide and nearly empty boulevards of Paris to great effect: the combatants are exposed and vulnerable. This open aspect is contrasted by filming other scenes in the interiors of cars, shops and buildings. Clément also make telling use of overhead shots, often from the viewpoint of Resistance fighters ambushing German units. Other effective scenes make good use of concealed viewpoints: half-open windows and doors, barricades, car windows. At other time he sets his camera at the level of combatants lying down or kneeling for concealment. Several scenes have considerable power - SS troops on the prowl, the muzzle-fire from their weapons irradiating like strobe-lights, a couple crawling across an ominously empty boulevard while under fire, a tank firing down a shop-lined street.

Réne Clément's movie took the traditional view of the Liberation of Paris, and the attitude of French people towards the Nazi Occupation. That is, the Liberation is portrayed as a triumph of popular French determination to overthrow Nazi rule, a determination exemplified by the courageous struggle of Resistance forces, which readily ignored their differing political outlooks in order to unite to overthrow the hated German occupiers and liberate Paris.

This view was increasingly being attacked even as the film was being made. Communists claimed that their members were the dominant force in the Resistance and in opposing the Germans in Paris; supporters of President Charles de Gaulle claimed that the Gaullist Free French forces and Gaullist-oriented Resistance units were crucial. Veterans of the Division Leclerc and other Allied forces demanded that their role in liberating Paris be emphasised. DeGaulle's own role was contentious. His supporters regarded him as the saviour of Paris and France; his opponents insisted he was an arrogant and divisive figure who took credit for the contributions that other French men and women had made in their struggle against the Nazis. Another even more discordant element emerged in the publicity over the book and its transference into a movie. It was becoming clear that the majority of Parisians were acquiesced passively in the German occupation, and a considerable number actively assisted Occupation forces and / or profited economically or politically from that Occupation. Very few French actually joined or helped the Resistance. It was only when it became clear that the Allied invading forces had established an irreversible presence in France that the populations of Paris and other French cities decided to rise up against their German occupiers.

Not only did the movie face this mixture of embarrassment and backlash against the traditional heroic view of the Liberation. It became mired in the controversies about President de Gaulle. His political opponents of left and right in France denounced the film for presenting him as a a popular and unifying force. In America many hated him for his 1966 demand that US forces leave Vietnam and his decision that same year to pull France out of NATO. Many in Britain also resented that stance, as well as his negative attitude towards British entry into the EEC. Many Anglo-Americans accused him of ingratitude: he had been willing to accept Allied help during World War 2 but had now turned his back on his former benefactors. And with peace movements and anti-war demonstrations flourishing, an American-financed film about military exploits was unlikely to do well.

One unfortunate result of the various backlashed against the movie was the disastrous effects on the reputation of its director, Réne Clément. His reputation never recovered from the critical and financial mauling the film received. The New Wave-style aficianados already regarded his carefully-honed, well-crafted and subtle films as old-fashioned, so the failure of Paris provided them with a perfect opportunity to condemn his oeuvre.

What's good about Is Paris Burning?

1. The decision to film in black-and-white documentary style, making frequent use of hand-held cameras, and using the actual locations (or close approximations) makes for an authentic experience. At times it seems as if you are there on the streets of Paris watching events. The integration of actual documentary footage with film is very well done, especially considering that the film was made years before the days of CGI and computerisation. Features of this style were used years later to good effect by Spielberg in Schindler's List.

2. Many of the sequences in the movie are exciting and convincing. Clément is brilliant at action set-pieces, especially scenes of Resistance fighters ambushing German troops. His use of the widescreen format cleverly uses the wide and nearly empty boulevards of Paris to great effect: the combatants are exposed and vulnerable. This open aspect is contrasted by filming other scenes in the interiors of cars, shops and buildings. Clément also make telling use of overhead shots, often from the viewpoint of Resistance fighters ambushing German units. Other effective scenes make good use of concealed viewpoints: half-open windows and doors, barricades, car windows. At other time he sets his camera at the level of combatants lying down or kneeling for concealment. Several scenes have considerable power - SS troops on the prowl, the muzzle-fire from their weapons irradiating like strobe-lights, a couple crawling across an ominously empty boulevard while under fire, a tank firing down a shop-lined street.

At its best, Is Paris Burning? has thrilling and authentic sequences of urban warfare.

The best scenes seem like actual photos of events (below) brought to cinematic life.

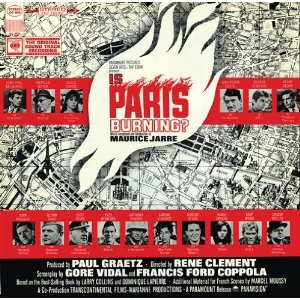

3. The film's music is one of composer Maurice Jarre's very best, although it has not achieved the fame of his work for Dr. Zhivago or Lawrence of Arabia. It is an unusual but effective mix of brass, strings and accordion, using both sentimental ballads, a charming waltz, and strident marches.The album is now much sought-after by collectors of movie soundtracks and Jarre fans.

Original album cover below Recording of Overture

Original album cover below Recording of Overture

Decide for yourself -Two sequences from Is Paris Burning?

|

|

|