Hollywood v. Pinewood

Conflicting New Zealand perceptions of American & British movies

From the 1920s to the 1940s, Hollywood movies were regarded by most of New Zealand's cultural guardians as not only inferior to British cinema, but also as endangering the nation's British heritage -and its morals. The New Zealand public, however, knew otherwise.

During the era from 1918 to the early 1950s most of New Zealand educationalists clergy, ,public intellectuals. civic worthies, M.P.s and other cultural guardians not only complained about Hollywood’s supposedly salacious influence. Not only were American films undermining the nation's traditional British values and customs. These criticisms were usually accompanied by an exaltation of the moral, social and artistic virtues of British films. Thus in 1921 an indignant citizen wrote to the Minister of Internal Affairs complaining that the preponderance of American films was undesirable in a country with a British cultural heritage ‘native to us’. In 1934 New Zealand's Governor-General Lord Bledisloe claimed ‘all right-minded people’ wanted the New Zealand public to demand a ‘wholesome type of [cinematic] entertainment’ in lieu of the current demand for ‘unsavoury, unwholesome, morally defiling pictures’. These, he recommended, should be replaced by what he called ‘good, sound’ British films. Moral entrepreneurs who compared American and British movies contrasted the perceived vulgarity and coarseness of the former with theallegedly higher-toned British cinema. In 1930 Mrs N. Molesworth, Inspector for the Society for the Protection of Women and Children, claimed ‘British films are not so pointedly disregardful of the decencies of life, nor do they unduly emphasise the unpleasant or the suggestive’.65 Two years later the Women’s Institutes of New Zealand resolved that ‘English films’ be supported and that ‘foreign’ [i.e. American] films that ‘lowered the standard of morality and good taste’ be ‘eliminated’.

However, interwar New Zealand movoegoers had better taste than their cultural and social superiors.. A local cinema manager observed that patrons ‘will not pay to see British talkies simply because they are British. The demand is for quality, and experience has shown that in this direction America is ahead of Britain’. A suburban projectionist of the era commented that at his Ponsonby [Auckland] cinema members of the public would ring the cinema in advance of a double screening. If they found out that the first film on the double-bill was British, they would arrive at halftime.

When the Auckland cinema impresario Henry Hayward set up the London Theatre to show only British films in 1928, ‘Everyone thought it a happy idea; but the Box Office said “No!”’ After eight weeks Hayward’s experiment ended in failure; we went back to a programme heavily weighted with Hollywood films.67 Some New Zealanders felt that British films were so bad that they imperiled Britain’s ‘racial prestige’ abroad.68 And In 1926,, New Zealand’s High Commissioner in London, James Parr, an influential and prominent figure in Auckland and national politics for decades, declared that the most influential factors in New Zealand since 1910 had been ‘motor cars and the cinema’. He claimed that ninety-five per cent of films shown here were ‘cheap, trashy American’ movies, which disseminated ‘pernicious un-British propaganda’. The British Empire was endangered by what Parr called ‘the Americanisation of the Dominions and the Colonies by Hollywood’.

In 1934 New Zealand's Governor-General Lord Bledisloe claimed ‘all right-minded people’ wanted the New Zealand public to demand a ‘wholesome type of [cinematic] entertainment’ in lieu of the current demand for ‘unsavoury, unwholesome, morally defiling pictures’. These, he recommended, should be replaced by ‘good, sound’ British films.Other moral entrepreneurs who compared American and British movies emphasised the perceived vulgarity and coarseness of the former. In 1930 Mrs N. Molesworth, Inspector for the Society for the Protection of Women and Children, claimed ‘British films are not so pointedly disregardful of the decencies of life, nor do they unduly emphasise the unpleasant or the suggestive’. Presumably Mrs Molesworth had not seen many British movies.

However, interwar New Zealand movoegoers had better taste than their cultural and social superiors.. A local cinema manager observed that patrons ‘will not pay to see British talkies simply because they are British. The demand is for quality, and experience has shown that in this direction America is ahead of Britain’. A suburban projectionist of the era commented that at his Ponsonby [Auckland] cinema members of the public would ring the cinema in advance of a double screening. If they found out that the first film on the double-bill was British, they would arrive at halftime.

When the Auckland cinema impresario Henry Hayward set up the London Theatre to show only British films in 1928, ‘Everyone thought it a happy idea; but the Box Office said “No!”’ After eight weeks Hayward’s experiment ended in failure; we went back to a programme heavily weighted with Hollywood films.67 Some New Zealanders felt that British films were so bad that they imperiled Britain’s ‘racial prestige’ abroad.68 And In 1926,, New Zealand’s High Commissioner in London, James Parr, an influential and prominent figure in Auckland and national politics for decades, declared that the most influential factors in New Zealand since 1910 had been ‘motor cars and the cinema’. He claimed that ninety-five per cent of films shown here were ‘cheap, trashy American’ movies, which disseminated ‘pernicious un-British propaganda’. The British Empire was endangered by what Parr called ‘the Americanisation of the Dominions and the Colonies by Hollywood’.

In 1934 New Zealand's Governor-General Lord Bledisloe claimed ‘all right-minded people’ wanted the New Zealand public to demand a ‘wholesome type of [cinematic] entertainment’ in lieu of the current demand for ‘unsavoury, unwholesome, morally defiling pictures’. These, he recommended, should be replaced by ‘good, sound’ British films.Other moral entrepreneurs who compared American and British movies emphasised the perceived vulgarity and coarseness of the former. In 1930 Mrs N. Molesworth, Inspector for the Society for the Protection of Women and Children, claimed ‘British films are not so pointedly disregardful of the decencies of life, nor do they unduly emphasise the unpleasant or the suggestive’. Presumably Mrs Molesworth had not seen many British movies.

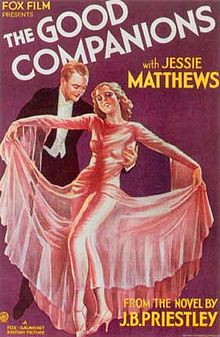

British studios used the same genres that their Hollywood counterparts relied on (except for Westerns), although with less technical expertise and a more limited range of style and acting. A typical example was the 1930s British musical The Good Companions. Based on J.B. Priestly's very good best-selling novel about an itinerant performing troupe in depression era-England,, it starred Jessie Matthews, a singer and dancer with a distinctive "plummy" upper-class accent which belied her struggle upwards from a poverty-stricken Soho childhood with 10 siblings. British studios tried to present as a sort of Ginger Rogers and it was hoped that she might team up with Fred Astaire in a musical, but that never happened. Incidentally the movie also cast John Gielgud as a down-on-his luck impresario